|

When Sophie de Grouchy married Condorcet on 28 December 1786 at her childhood home, the Villette castle, The Marquis of La Fayette was witness. Some, including Condorcet's friend Madame Suard, thought that Sophie was either in love, or having an affair with La Fayette (who was then married). There is no evidence whatsoever that this was the case. Sophie remained close to La Fayette and his family and named his dautgher, Madame de Lasteyrie one of her executors. During the early years of the revolution, however, when the counter-revolutionary press was still fighting hard – and dirty! – a pornographic caricature of Grouchy and La Fayette together was published in the royalist press. But in 1791, when La Fayette ordered the army to charge into the crowds on the Champ de Mars, Sophie, and her infant daughter, were among those who had to run. Sophie de Grouchy was not the last important female friendship in La Fayette's life. In 1820 he was introduced to the young Frances Wright, Scottish writer who had travelled to America to witness the republic there, and went on to develop her own republican arguments for a more radical republic that abolished slavery and gave women equal rights. Frances Wright and La Fayette presented themselves as adoptive father and daughter – a relationship that was not always recognized by his own children and therefore was never formalized. When they travelled together to America, presenting Frances as his daughter helped avoid certain misunderstandings.

0 Comments

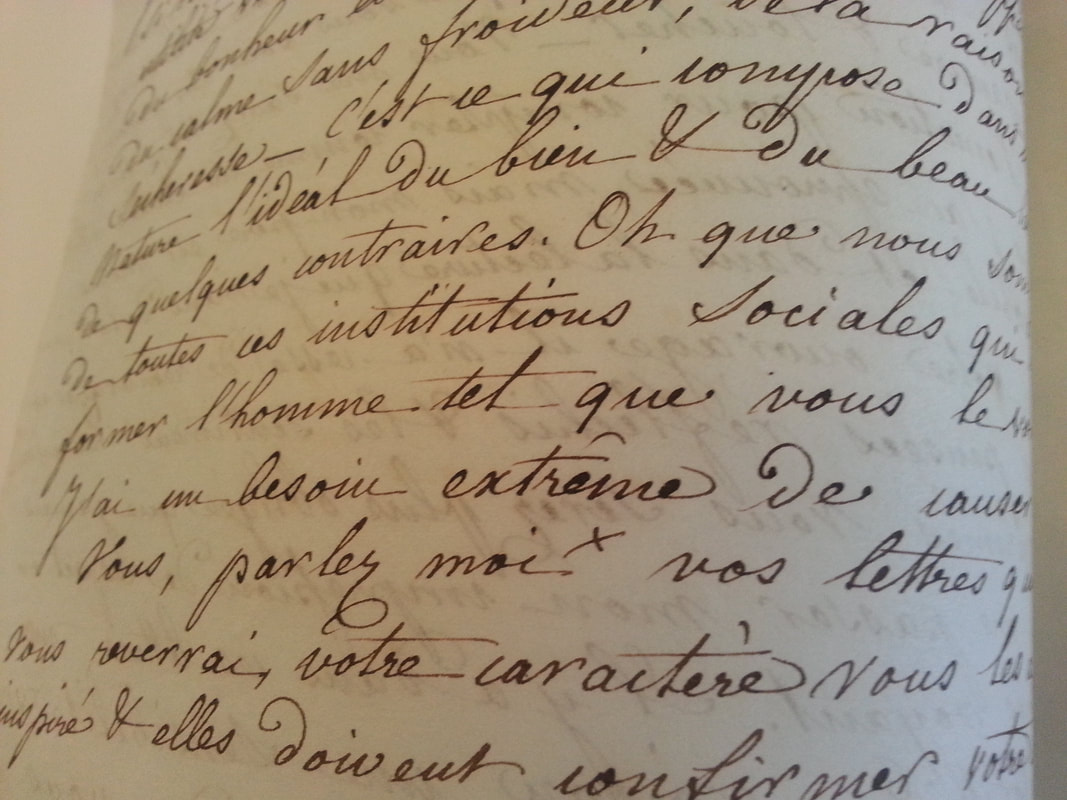

After Condorcet's death, Sophie kept up her salon, first in Auteuil, in the house next to Madame Helvetius, and later in Meulan, close to the castle of Villette where she had grown up. The house she bought had been built in 1642 by Anne of Austria for the religious order of the Annonciades. It was several storeys high and set in the countryside, between the town and the castle of Villette. The nuns who’d occupied it had been evicted 5 years previously and the house had already exchanged hands a few times. Sophie called it the ‘Maisonnette’ or little house, despite its generous size. One of the rooms was a large salon where she could host her philosophical circle, and there were several bedrooms upstairs for guests. (for more on the purchase and the set up of the house, see Madeleine Arnold-Tetard's excellent blog.) Sophie’s salon was a place where she could discuss her ongoing work with close friends such as Cabanis, it was a meeting place for the Ideologues, and it also played a role in facilitating other’s literary careers. Karl Benedikt Hase, a Byzantine expert who came to play an important role in the literary world of 19thCentury Paris, was first introduced to this world by a chance meeting with Sophie de Grouchy. Having walked on foot to Paris from Weimar, and arriving a poor student, he was recommended to various people for his knowledge of Ancient Greek, and brought to Meulan by Sophie’s lover, Fauriel: I already talked about Madame Concordet in one of my letters. I got to know her by chance; she wanted to learn German and a certain Fauriel, private secretary to the police minister, with whom I sometimes spend the evenings, sent me to her. It was the 28th Frimaire; look up the date and underline it, it is one of the most important in the life of your friend. I’ll admit it – the clear mind of this wonderful woman, her joy in the all-pervasive progress of humanity to a marvellous goal, her knowledge of the great moments of the revolution, in which she herself played a not insignificant role (on the day before the 10th August, when Concordet, her husband, played host to 400 Marseillese, she was the queen of the party), perhaps also her friendly attitude towards me – for my significant progress in French pronunciation, which has astonished everyone, was thanks to my reading French tragedies aloud to her – could not fail to have an effect on me. Around the time that the guillotine was first tried, Sophie de Grouchy was finishing a draft of her Letters on Sympathy. The letters are a both a commentary and a response to Adam Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments in which the Scottish philosopher argued that morality arises out of our reactive attitudes and the sympathythat human beings naturally feel for each other. For Grouchy sympathy develops from the first relationship an infant experiences, that is from the proximity with another living body, and the dependence it develops with it. Because sympathy is developed through contact with others, it is natural that the Letters discuss crowd psychology: Amongst the effects of sympathy, we can count the power that a large crowd has to affect our emotions [...]. Here are, I believe, a few causes of these phenomena. First, the very presence of a crowd acts on us through the impressions created by faces, discourses, or the memory of deeds. The attention of the crowd commands ours, and its eagerness, forewarning our sensibility of the emotions it is about to experience, sets them in motion. This passage is reminiscent of the Roman Stoic philosopher Seneca’s Letter to Lucilius, in which he describes the powerful – and worrying – effect that crowds can have on the wisest, calmest of individuals. He writes how, on occasions when the emperor forced him to attend gladiator shows, his blood was raised and he too wanted to shout that one should die and another live. To consort with the crowd is harmful; there is no person who does not make some vice attractive to us, or stamp it upon us, or taint us unconsciously therewith. Certainly, the greater the mob with which we mingle, the greater the danger. Grouchy tried to pinpoint the cause of this response. It is the overwhelming presence of living bodies, all in one place, all speaking, moving, twitching in their own way, but at the same time all focusing their attention on the same point, which both confuses us and takes over our own sense of direction: we too want to look where they look, and we too are getting excited with the anticipation of what will happen there. The description of the effect of crowds in the Letterson Sympathyalso touches on the paradox of tragedy – why do we enjoy tragedy so, if we find other’s pain distasteful? The question is as old as Aristotle, who saw in tragedy a way to educate one’s emotion, to learn to understand and manage them. This is also where Grouchy is going here: In any case, we know that the spectacle of physical suffering is a real tragedy for the masses, a tragedy they seek only through a dumb curiosity, but whose sight sometimes arouses the kind of sympathy which can become a passion to contend with (Letter 4). No doubt Grouchy also has the spectacle of the public execution in mind here. When she first drafted the letters, executions were most commonly hangings, and they were always public, in France as elsewhere. People came to watch, and bought snacks and souvenirs, as they would at the theatre. And as we know, a year after writing this, she mingled with the crowds going to the guillotine, in order to visit her husband in hiding. Not many in the eighteenth century agreed that women should be writers of anything other than gossipy letters. But even those who did found it hard to agree as to when was the best time for a woman to become a writer. A woman who had the misfortune not to be married or have children could write at any time, provided she did not disturb her relatives. Hence Jane Austen would get up early, before her family’s breakfast, and write at the dining table. Afterwards there was household tasks to attend to, of course, and any other time she could take up a pen was devoted to writing letters to family members who were away. Considerations of respectability only applied to respectable women, of course. So Olympe de Gouges, widowed, living under her assumed name instead of her husbands (Aubry), bringing up her boy alone, assisted financially by her lover, and pursuing a career as a playwright could write when she wanted to. This is probably why her biographer lists over 140 pieces penned by Olympe in the last five years of her life. (Her writing career began 1788 and she died in 1793) Little is known of Sophie de Grouchy’s writing habits, except for a report from her aunt that as a twenty year old, staying in a convent finishing school in Normandy, she spent so much time reading and translating that she made herself ill and damaged her eyesight. Given that the social life of the school was quite active – the idea was for the young women to be presented to society and hopefully find husbands – Sophie probably worked during the night, by candlelight. The only obstacle standing between her and her work then was her social life, and it is likely that even when she married and became a mother this carried on, i.e. that her activities as a saloniere were the only thing that stopped her from writing when she wanted to. Her daughter, Eliza, had a wetnurse, so that Sophie was not bound by the usual duties of motherhood. Manon Roland was firmly opposed to wet-nursing, being a follower of Rousseau, and a middle class woman, less able to ‘adopt’ a nurse, i.e. invite a woman to become a permanent member of the family and live under their roof until she could be retired. Manon also had some duties at home. Even though she had servants, they had to be trained, supervised, their work had to be done for them when they were sick and big jobs, such as laundry, had to be shared, and dinner had to be ordered, and prepared by herself when she wanted something done in a particular manner. And most importantly, children – in her case a daughter, Eudora – had to be educated following Rousseauian precepts. But none of this, Manon reflected, ought to take particularly long, so that a good mother and housewife ought still to have plenty of time for study and writing. Those who know how to organize their work always have leisure time. It is those that do nothing that lack the time to do anything. Moreover it is not surprising that women who spend their time in useless visiting and who think they are badly dressed if they have not spent a great deal of time at their mirror, find their days too long through boredom and too short for their duties. But I have seen those we call good housewives become unbearable to the world and even their husbands through a tiresome attention to little things. Manon’s stance was not unlike that of Mary Wollstonecraft, who claimed that a married middle class woman with children was in an ideal position, once her children were at school and no longer needed her full time attention, to take up science, literature or the arts. And did they pursue a plan of conduct, and not waste their times in following the fashionable vagaries of dress, the management of their household and children need not shut them out from literature, nor prevent their attaching themselves to a science, with that steady eye which strengthens the mind, or practicing one of the fine arts that cultivate the taste (VRW). Both in Roland and Wollstonecraft’s case, however, the life plan that would allow women to write while mothering young children relied very much on a reformed, republican and proto-feminist model of family life in which only necessary household duties were perfomed - the ‘vagaries of dress’ to be avoided and ‘if men do not neglect the duties of husbands and fathers’. I expect a woman to keep her family’s linen and clothing in good order, to feed her children, order, or herself cook dinner, this without talking about it, keeping her mind free and ordering her time so that she is able to talk of something else, and to please, at last, through her mood, as well as the charms of her sex So what would an 18th woman who wanted to write but had no expectations that a revolution would bring about major changes in her household duties do? This was the case of Hannah Mather Crocker, born in Boston in 1752, writer of several books and pamphlets, including “Observations on the Real Rights of Women” a work in which she cites Wollstonecraft amongst others. Crocker, although she had always been philosophically inclined, only began to write in earnest once her ten children had left home, remarking that this period in a woman’s life was : a fully ripe season to read, write, meditate and compose, if the body and mind are not enfeebled by infirmities. In other words, if bringing up ten children hasn’t left you a mental and physical wreck, now is the time to pursue a literary or philosophical career!

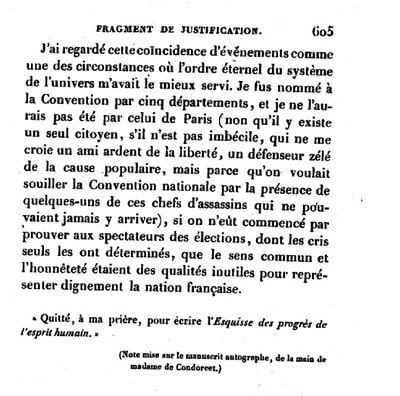

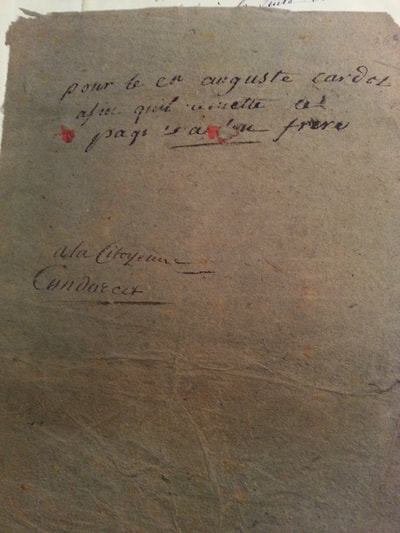

On 19 June 1792, the Jacobin club of Marseilles wrote to Jerome Petion, the mayor of Paris warning him that the King, with his corrupt civil list, was a threat to French Liberty, and that they were ready to come and lend a hand. A few days later, a deputation of 500 Marseillais set off for Paris on foot – over 700 km. Their leader, a captain from Montpellier, sang for them a war song celebrating the Revolution, written by Rouget de Lisle. On 30 July, the Marseillais entered Paris singing that same song. One can only imagine what 500 hungry, thirsty, and possibly ill soldiers suddenly entering the Capital must have been like. And of course, they had come for a reason, to confront the King and defend Liberty. So it’s no surprise perhaps that on 10 August, they took part in the massacre of the Swiss guards in the Tuileries. But before they did, 400 of them made a stop at the Hotel des Monnaies, the home of the Condorcets. The building is not small, nonetheless, making space for, and serving 400 scruffy soldiers must have been a challenge. But if it was, Sophie met it well. According to her biographer, Guillois, she was the ‘Queen of the party’, and that: she charmed them so well that she could have, had the Gironde listened to her, saved, with the help of the Marseillais, Coutnry and Liberty. While in hiding, Condorcet started to write an apology (Justification) which was meant to explain and justify his role in the revolution, and show that he had been wronged by his persecutors, the Jacobins. Sophie, sensing that this work would be of little value philosophically or personally, urged him to give it up, and instead to turn back to a work he had begun several decades before: a history of the progress of human nature. Although we do not have any hard evidence that they wrote together, it seems likely that some of the passages in particular are hers, and that others are the product of a collaboration between husband and wife. We do not have a final manuscript that corresponds to the first edition by Grouchy, which suggests that she added some paragraphs herself. The only existing manuscript, dedicated to Sophie, is very messy, and would have required much editing to make sense of the marginal annotations and in text corrections. Several of the differences concern women and the place of the family in human progress. Perhaps these were ideas she and Condorcet had discussed and that she knew he wanted included. Perhaps these were points she had suggested to him in their discussions. In March 1794, Condorcet run away from his hiding place in order to avoid getting his hostess arrested. He died a few days later in a village prison, but was not identified until several months after his death, so that his wife remained ignorant of his whereabouts. When several months later his remains were identified, the Convention commissioned three thousand copies of his new book, Esquisse d’un Tableau des Progrès de l’Esprit Humain from Pierre Daunou. Sophie de Grouchy prepared the edition and it was published in 1795. This edition was reprinted and revised at least twice by Grouchy (alone and with collaborators in 1802 and 1822), and it was translated into English the year it was first published, and John Adams owned a copy In 1847, the Académicien François Arago, noted that the 1795 edition contained passages which were absent from Condorcet’s final manuscript, produced a new edition with extensive revisions, which, he said, was closer to the original manuscript which he’d obtained from Grouchy and Condorcet’s daughter, Eliza O’Connor, and which he thought more accurate because in Condorcet’s hand. Arago’s edition is now regarded as authoritative. Not only was Grouchy’s name deleted from the work – where it did belong, perhaps as co-author and at the very least editor – but with it the emphasis she had brought on the role of women and the family in human development.

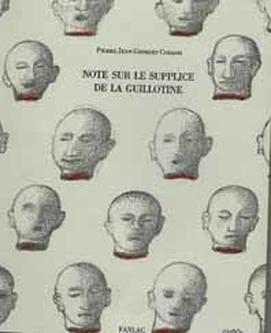

During a recent visit to the Conciergerie, I picked up a prettily bound book, entitled Note sur le supplice de la guillotine. The book contained a short essay of that title by Cabanis, five drawings by the artist Cueco, and a discussion of the moral and political philosophy of the guillotine by French philosopher Yannick Beaubatie. For the main part, Cabanis's article, written 1799 (an IV) argues against recent articles that claimed that the torment of the guillotine ought to be abolished because it cannot be proven that the guillotined do not feel pain. The articles (by members of the medical profession, Cabanis's own colleagues), cite as evidence witnesses's reports of decapitated heads moving in such a way as to suggest that they responded to the situation, and attempted to communicate. One example they cite is that of Charlotte Corday, whose decapitated head was slapped by one of Sanson's valets, after which it apparently reddened as if in shame and indignation. Cabanis answers that while he was not present at any decapitation (as he did not have the stomach for it) he was present at the testing of the machine and certifies that death must be instanteanous. He then goes on to discuss the philosophical question of where pain resides, and the medical phenomenon of bodily movement after death. At the end of the essay, Cabanis offers his moral and political reflections: the death penalty, he claims, ought to be abolished. But if it is not, the guillotine has to go. Not because it causes pain to its victim, but because it is too swift so that as a performance of a punishment it cannot serve its rightful purposes. Beaubatie takes this up in a fascinating discussion. In particular, he notes a resemblance between Cabanis' s reservations about the guillotine and Beccaria's utilitarian theory of punishment. Beaubatie notes further that Beccaria and Cabanis both frequented the Helvetius home, although two years apart. What Beaubatie does not note, however is the strong resemblance between Cabanis's thought and that of his sister in law and long term friend and collaborator Sophie de Grouchy. Cabanis's principal reason for thinking that the guillotine should not be used is not - as Beaubatie claims - that it cannot serve as an exemple or detterrent, but that it does not allow enough time for spectators to react emotionally in such a way that would help their sympathy grow. The guillotine’s work is done in less than a minute. That it did not occur to Beaubatie, in his commentary written in 2002, to look to his long term philosophical correspondent Sophie de Grouchy for influence, as well as to Beccaria (whose path with Cabanis crossed, but two years apart) is a sign of how much work has been done over the last fifteen years in recovering the works and influence of women philosophers. In May 1792, before Mary Wollstonecraft set out for Paris, where she was to act as a war journalist for her publisher Johnson, a French translation of her Vindication of the Rights of Woman came out. Before traveling she wrote to her sister: "I shall be introduced to many people, my book has been translated and praised in some popular prints". So who was the author of this translation that was so favorably reviewed?

La Défense des Droits des Femmes was translated anonymously. Isabelle Bour suggested that it might have been translated by a member of the Girondin circle. This is quite plausible as we know that the Girondins did defend to some extent women's rights. Condorcet published an article arguing that women should be given equal political rights to men in 1791, so that Wollstonecraft's book would have struck him as important and topical. So who was close enough to Condorcet to share his views on women and citizenship, knew enough English to read the Vindication and was an experienced translator? Sophie de Grouchy, of course. We have already speculated as to whether she had read anything by Wollstonecraft, and whether she could have met her. This is another possibility to add to the mix. Although Madame de Stael is well known, as a historical figure and a writer, she remains very much in the background of the research I have conducted so far on the women of the French Revolution. I mentioned Roland's quip about her salon in my last post. This is as close as the two women got. Stael and Gouges never met, and although she and Grouchy moved in similar aristocratic and international circles, they were certainly not friends. Germaine de Stael was the daughter of Jacques Necker, a Swiss banker appointed by Louis XVI as finance minister in 1777. Necker held this post until 1781, when he was dismissed for having hidden the debts of France in his reports. He was recalled briefly in 1788, but dismissed again on 12 July 1789. Camilles Desmoulins, in the famous speech rousing the French people to revolt, invoked the King's treacherous treatment of Necker. Necker comes across as something of a quiet hero of the revolution, a man who did his best to resist the decadence of the French regime and serve the people. This is certainly how his daughter saw him. However, to see him as such we must leave out the story of how he became minister in the first instance. In 1776, Turgot was minister of finances, and Condorcet, director of the mint, his right hand. This was a difficult period for the French economy, marred by the flour wars, the rising price of grain which resulted in famines, and the ensuing revolts. Turgot attempted to deal with the crisis by getting rid of a number of regulations (including pricing) which had a throttling effect on the production of bread. But before he could succeed (or fail) he was dismissed and replaced by Necker. People in Turgot and Condorcet's circle believed that Necker had had a hand in his dismissal, privately misrepresenting to the King what Turgot was doing. Condorcet, when Turgot was dismissed, did not want to continue in his position. But the King ordered him to stay. This background of political squabbling may explain why Grouchy and Stael never became friends. Each was loyal to her husband or father. The rift grew bigger when the Condorcet's close friend and ally, Mirabeau took over from Necker in the heart of the French people. Necker left France, and after 1789, had no role to play in revolution. Stael fled Paris in 1792, after the September massacres, and took her salon to her chateau in Switzerland. When Napoleon came into power, he took an instant dislike to her, and she had to exile herself again. As powerful figures in French literary circles, however, Stael and Grouchy could not ignore each other. And when Grouchy's Letters on Sympathy came out in 1798, Stael wrote to her, admitting that she envied both her style and the depth of her analysis. It is not clear whether Sophie de Grouchy took the homage seriously.

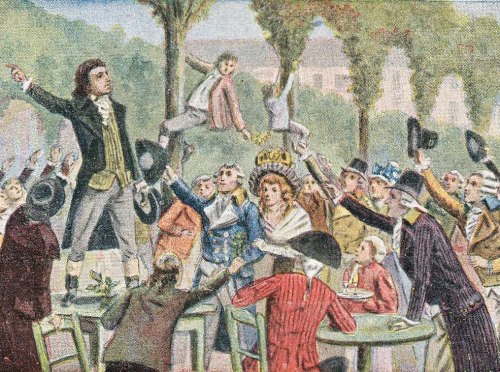

Wilhelm von Humboldt, who visited Sophie in 1799 reported the letter in his Journal Parisien. "She showed me a letter which Madame de Stael had written about her book to which she gave exaggerated praise" In July 1791, just as Le Republicain was getting ready to print its first issue, the King, who'd try to run away from France with his family, was caught in Varenne, recognised because of his likeness to the profile printed on a coin. He was brought back to Paris, and the Assembly, much relieved that they wouldn't have to do anything truly radical, decided to keep him on as the head of a constitutional monarchy. This roused the republicans, and Brissot, often their spokesperson, drafted a petition to have the king removed from office. The word spread and on 17 July a huge crowd gathered on the Champ-de-Mars for the purpose of signing the petition. The Champ-de-Mars, now the site of the Eiffel Tower, was then a large empty space which had been chosen to celebrate the first 'Fete de la Federation' on 14 July 1790. As is often the case in large gatherings, a few detractors made trouble, there was a fight, and possibly a death or two. This was enough for the Assembly to declare court martial and the army, headed by La Fayette, fell onto the crowd with their bayonettes.

It is unknown how many died or were wounded, but the event is refered to as the Champ-de-Mars Massacre. Both Sophie and Manon were in the crowd, both with their daughters. The Marquis de la Fayette, famous for his role in the American Revolution had been a close friend of Grouchy before her marriage to Condorcet, and was generally in sympathy with Brissot and his friends. This, of course was the end of the friendship. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed