|

In the spring 1792, Sophie de Grouchy, Marquise de Condorcet wrote to her friend Etienne Dumont, speech writer for Mirabeau, and translator for Jeremy Bentham, sending him some of her manuscripts for feedback. "Here are the inchoate manuscripts I mentioned to M.Dumont, or rather the indecipherable sketches. I have lost the eighth letter on sympathy. As to the other mess, it contains as yet only a few weak traces of a development of character and passions, and that is not yet strengthened by any of the circumstances that make a novel interesting. One of the main causes of my laziness when it comes to working on it is 1) difficulty in obtaining good advice (will some arrive from overseas!) 2) the fear of not having the means of executing the ideas which, in other hands could enrich the subject matter, but in mine, will probably make it less. If M.Dumont were to dine here this Tuesday, I would be in a better position to take heed of his advice, but also, they might be more frank if they are in writing. There is no need, I know, to ask him to speak to no-one of that which I send him." Letter to Dumont, spring 1792. Apparently, Dumont did not reply, and either he did not come to dinner, or the conversation did not turn to Sophie's writings.

"You are a merciless man for poor authors, especially a for a shameful author like a woman. What would it have cost you to tell me whether what you'd seen from my drafts deserved to be developed? I give you my word you would have had no grief from it." 19 May 1792. Why did Dumont not reply? Perhaps, despite his friendship for Sophie, he was not entirely persuaded that women should waste their time in literary pursuits, or that their contributions would be particularly good. Or perhaps he did not wish to spend his leisure time doing for free what he did for a living! Fortunately, the Letters on Sympathy were already fully drafted, and six years later she published them, together with her translation of Smith's Theory of Moral Sentiments. Unfortunately, we know nothing of the novel. Was she discouraged by Dumont's refusal to talk about it, and did she give in to the laziness she refers to in the first letter?

0 Comments

Manon Roland, we saw, did not like to write in her own name. Her reasons were as follows:

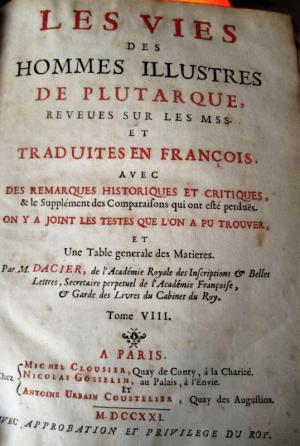

"Never have I had the slightest temptation of becoming an author; very early, I saw that any woman who would earn this title lost much more than she gained. Men do not like her, and her own sex criticize her: if her works are bad, she is mocked, and quite rightly. If they are good, they are taken from her. If one is forced to recognize that she did produce the best part of it, her character, her morals, her behavior and her talents are dissected to the extent that her wit’s repute can be balanced against the weight given to her weaknesses." And she made it clear to others that she knew just how inappropriate it would be for her to become a published author in her own name: “I know full well, Sir, that silence is woman’s ornament; the Greeks thought so and Mrs. Dacier wrote it, and despite our century’s general opposition to this sort of morality, three quarters of sensible men, husbands especially, still live by it.” (Manon Roland, 21 March 1789, letter to Varenne de Fenille), The anecdote Roland alludes to is reported as follows: Mrs Dacier, when asked to autograph the album of a learned German traveller, seeing the names of some very famous writers and scientists above hers, chose to copy this verse from Sophocles out of modesty. (Encyclopediana, Paris: Panckoucke, 1741.) Anne Dacier was in fact a classical scholar of some note, who worked first with her father, and then with her husband on a number of translation of Greek and Roman texts. She became famous for her translation of Homer, and for her preface to it, which was translated into English. She also wrote on aesthetics. Madame Roland was well aware of Dacier's success as an author. When, as a child, she'd read Plutarch's Parallel Lives she used the nine-volume integral translation produced by Anne and Andre Dacier in 1721. (Note, however, that only Andre Dacier is acknowledged as author on the title page).  Until a few weeks before she died, Manon Roland didn't want to publish in her own name. But she did publish either anonymously, or under her husband's name, 'helping' him with his work: "For twelve years of my life, I worked alongside my husband, as I ate, because the one was as natural to me as the other. If some part of his work was cited, because it was found to be more gracefully written; if some academic trifle such as he liked to send out was accepted by one of the learned societies he was a member of, I was happy for him, and I did not take particular notice whether the piece was one of mine. And often he ended up persuading himself that he had been on a particularly good streak when he'd written this or that passage which in fact came from my pen. [...]" When Roland was named minister of the interior, she kept on writing for him. She found it easy as 'she loved her country' and was 'enthusiastic for liberty'. Only once, she tells us, did she allow herself to be amused by her ghostwriting, when she penned a letter from the minister to the Pope, demanding the release of French artists imprisoned in Rome. #ThanksForTyping Elizabeth Vigee le Brun, the famous portrait painter of the late eighteenth century, was married to a man who saw her art as his private source of income. Finding that what she earned from painting portraits was not enough, he decided that she ought to teach. She recorded her reaction in her memoirs: "I agreed to his request without taking the time to think about it, and soon, a number of young ladies came to me, to whom I shewed how to make eyes, and noses and ovals, which I had to correct all the time. This took me away from my work and was a tremendous bore". One of her students, according to Guillois, was Sophie de Grouchy. Her biographer doesn't say when she had these lessons, but looking at the dates when Vigee le Brun was teaching, it must have been during the early years of Sophie's marriage to Condorcet, before the Revolution, when the couple were living in the Hotel des Monnaies in Paris and Sophie was attending lectures at the Lyceum, a school for the public set up by Condorcet and La Harpe. Although Sophie may have been one of Vigee Le Brun's irritating students, having to have her eyes and noses redone by the master, she nonetheless became a very decent miniaturist herself. We have several of her self portraits (including one in the nude). Sophie was in fact such a successful miniaturist that during the Terror she supported herself, her daughter, sister and her nurse by going around the prisons of Paris and painting the portrait of prisoners for their families. On two occasions, Guillois tells us, she avoided arrest by drawing the soldiers come for her for free.

Looking through some documents, I came across a pastel miniature portrait of Manon Roland, drawn, apparently, at the Conciergerie. There is no signature, and I have not been able to trace any information about it. But doesn't it just look like one of Sophie's? In his testament to his daughter, Condorcet tells us that his wife, Sophie de Grouchy, as well as her Lettres sur la Sympathie, wrote other texts in moral philosophy.

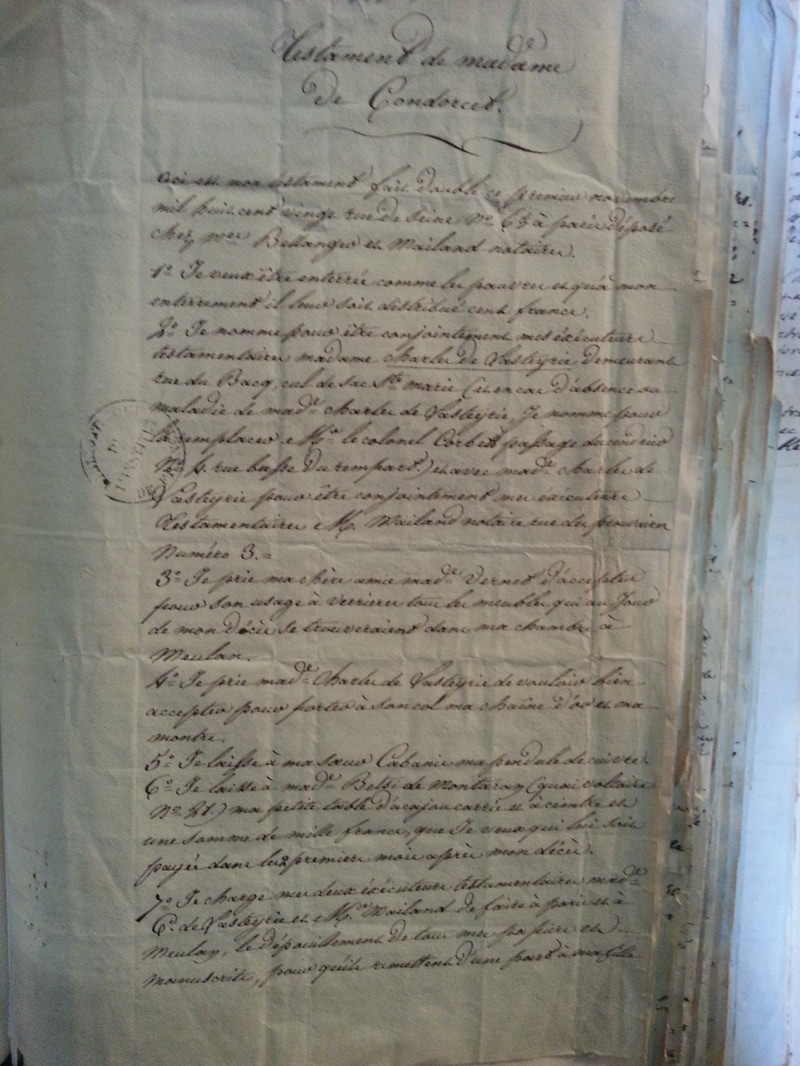

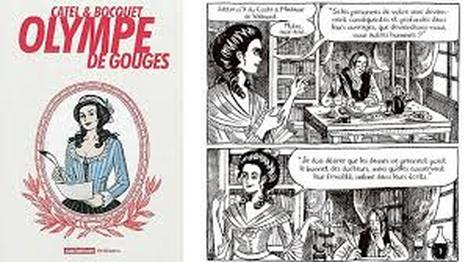

These are apparently lost, along with her manuscript of the Lettres. In the summer 2015 I visited the Bibliotheque de l'Institut in Paris, on the Quai de la Monnaie, where Condorcet and Grouchy used to live, and which houses all the papers related to the Academie Francaise. I was hoping to find some trace of her papers. I found her will, stating that she left her papers to her daughter, Eliza, and her sister, Charlotte Cabanis. Her executor was Madame de Lasteyrie, Lafayette's daughter. Next stop the Cabanis archives? When I work on a new historical author, I like to look for inspiration in fiction, art or cultural artefacts. To get in the mood for Christine de Pizan I watched Dreyer's 1928 The Passion of Joan of Arc and spent ages poring through medieval recipes in Le Menagier de Paris. When it comes to Olympe, there are several fictionalised biographies, but they are, to be honest, all a bit dreary. Catel and Bocquet's graphic novel, Olympe de Gouges, on the other hand, is truly inspirational. The history is detailed and as accurate as can be expected in a fiction, the character of Olympe is likeable and really fits the tone of her writings. The black ink drawings which become darker and less detailed as the story gets bleaker, really bring Paris, especially, to life. Also, it's a long book (488 pages) so you can really get stuck into it! Olivier Blanc, biographer of Olympe de Gouges, reports on Geneanet his struggles to maintain a truthful Wikipedia page on Olympe de Gouges:

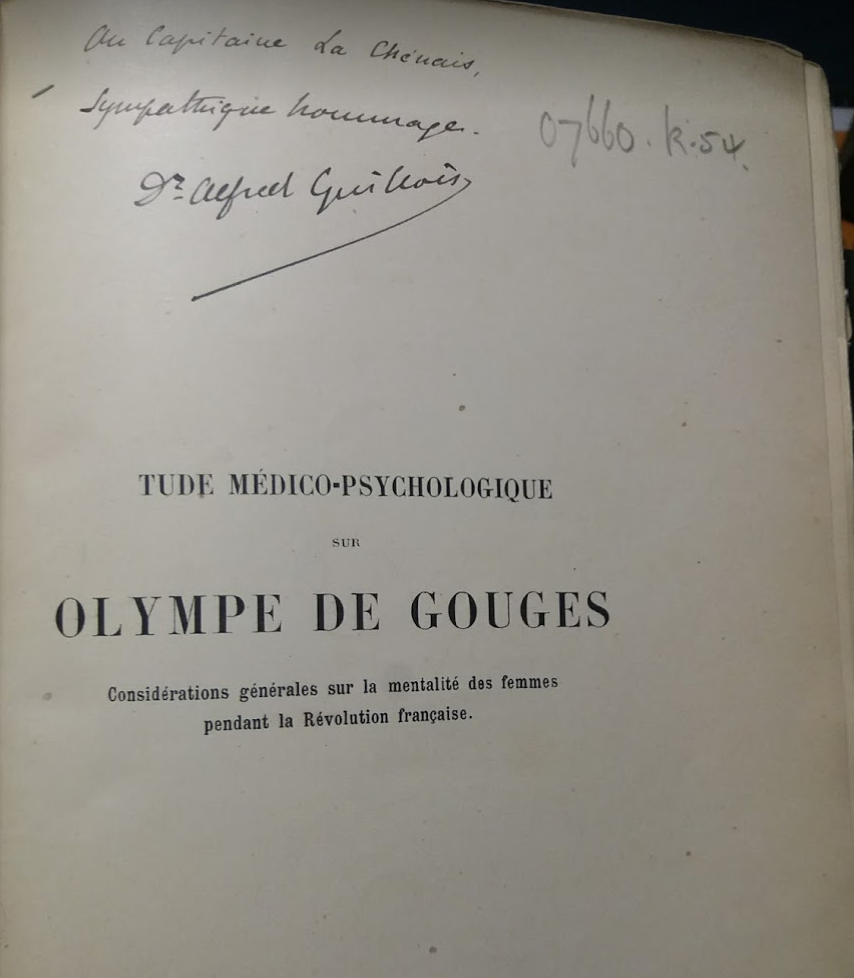

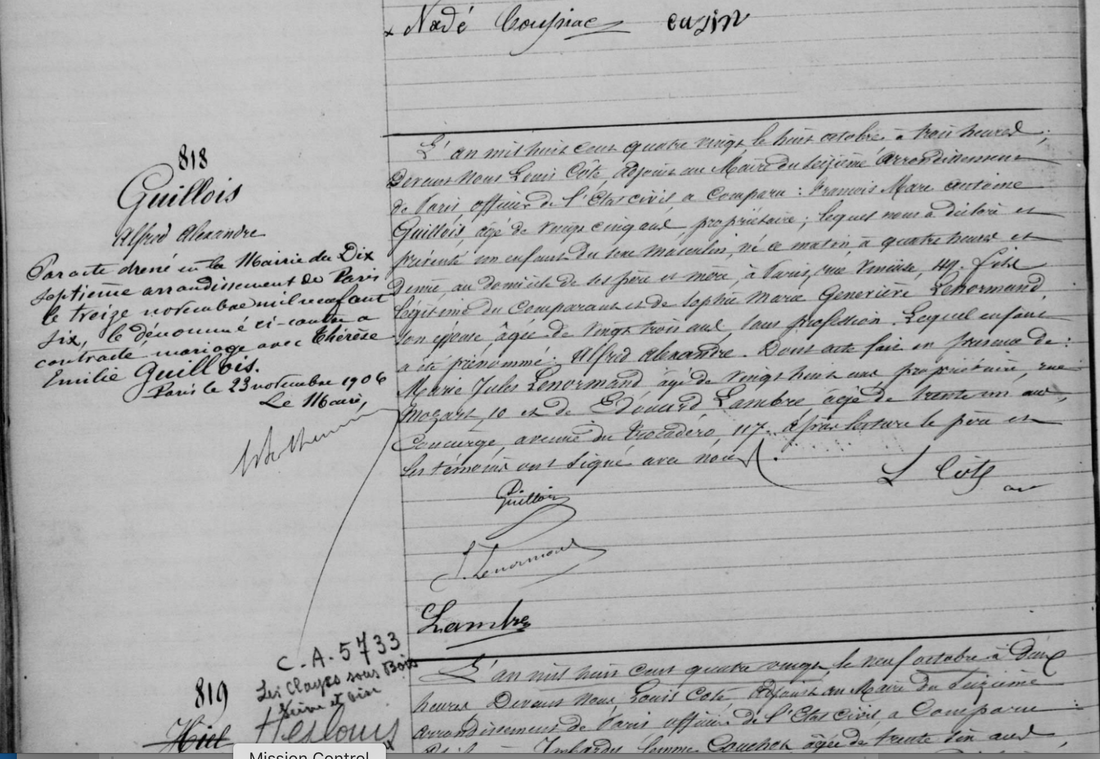

The gist, for those of you who don't read French, is that there are still people who care about the Jacobine/Girondist rift strongly enough that they are prepared to sabbotage each others' Wikipedia entries on the Revolution. Who said historians were boring? "A une époque où je pensais que l'encyclopédie en ligne Wikipedia était un projet sérieux, j'avais rédigé une première notice sur Olympe de Gouges, qui, depuis, a été grossie de toutes sortes d'informations bizarres, de caviardages et de censures. Comme souvent sur Wikipedia, des piratages discrets et intentionnels se sont agrégés à la notice d'origine. Le plus grave est la tentative de révisionnisme anti-Olympe de Gouges dirigé par Danielle Bleitrach (ex-rédatrice de ROUGE) et l'ineffable Florence Gauthier, qui s'inscrit dans un révisionnisme très actif depuis dix ans sur les pages Wikipédia relatives à la Révolution françaises. Il faut savoir que ces pages sont contrôlées par des militants promoteurs des thèses ultra-jacobines sur la révolution et la Terreur qui, par conséquent, rejettent ou dénaturent ce qu'ont représenté en leur temps Condorcet ou Olympe de Gouges. Les notices lourdes et niaises , toujours médiocres de Wikipédia Portrail révolution sont régulièrement modifiées, caviardées et surchargées de contre-vérités et d'interprétations qui n'ont aucun sens, Concernant l'appartenance d'Olympe de Gouges aux Club des Amis des Noirs, les censeurs-flibustiers de Wikipédia refusent par calcul à Olympe de Gouges l'honneur d'avoir appartenu de cette illustre société anti-esclavagiste. Or selon Brissot, Olympe de Gouges était bien membre des Amis des Noirs: "J'ai, écrit-il, cité quelques unes des femmes qui faisaient partie de la Société des Amis des Noirs. Je ne dois pas oublier, parlant d'elles, Olympe de Gouges, encore plus célèbre par son patriotisme et son amour de la liberté que par sa beauté et plusieurs ouvrages écrits parfois avec élégance, toujours avec une noble énergie. ADMISE DANS NOTRE SOCIETE (DES AMIS DES NOIRS), les premiers essais de sa plume furent consacrés aux malheureux que tous nos efforts ne pouvaient arracher à l'esclavage". Les papiers Brissot, en espérant qu'ils n'ont pas été pillés aux Archives nationales, comportait encore en 1993 l'extrait ci-dessus, tiré des "Mémoires" partiellement inédits de Brissot. Voir aux Archives nationales le dossier 446 AP 6 (lettre du 20 novembre 1792), et le dossier 446 AP 15 où il est encore question d'Olympe dans un extrait inédit des mémoires de Brissot, extrait dont est tiré la citation ci-dessus. Je ne suis pas retourné voir ce fonds qui, depuis, a été visité par M. Marcel Dorigny de la Société des Etudes robespierristes, lequel s'est intéressé à Brissot pour discréditer les Girondins." Sophie de Grouchy's first biographer was the civil servant, part-time historian Antoine Guillois. His book, La Marquise de Condorcet, sa famille, son salon, ses amis, portrays Sophie as a 'superior woman' praised for her beauty, her virtue and her intellect. Guillois dedicates his work to Sophie's grand nephew, the Vicomte de Grouchy. Olympe de Gouges also had a biographer named Guillois, a young medical student who chose to write his thesis on women's psychology during the revolution, focusing on one case, a woman clearly suffering from paranoid delusions, according to his expert diagnostic. Would it be too much of a coincidence if the two Guillois were related? It's by no means an uncommon name. In fact, in my searches, I discovered some Guillois of that period based in Turkey! But as it turns out, they are father and son, and here's the evidence on Guillois Junior's birth certificate (courtesy of a Guillois descendant , Jacques le Normand.

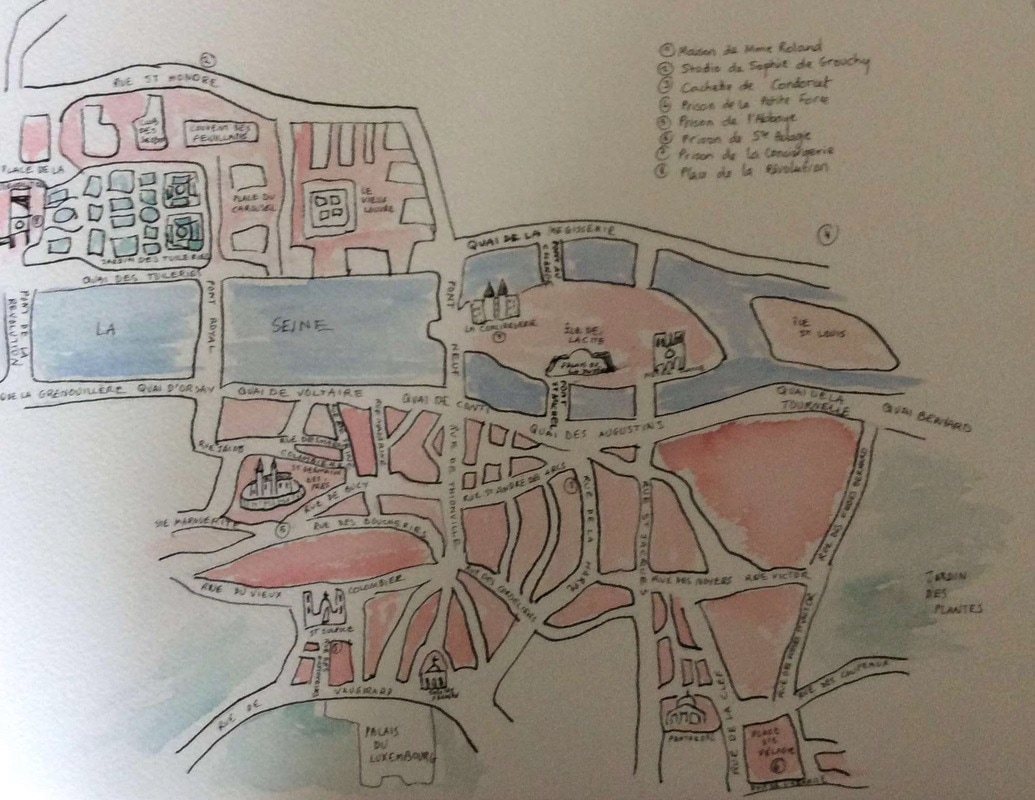

On 30 December last year, I took a walk in Paris with my daughter and her friend, to identify some of the places where Olympe de Gouges, Manon Roland and Sophie de Grouchy had lived or worked. We found very few actual buildings as many were destroyed when Paris was redesigned in the 19th century. We did find, however, the building on the Faubourg St Honore where Sophie de Grouchy set up her studio in 1793, when her husband, Condorcet was in hiding on the Rue des Fossoyeurs (we also found this building). Someone was entering the St Honore building, so we decided to sneak in behind them. We looked around, finding little of interest, Were we expecting discarded paint brushes or watercolour stains? But we were very pleased to have gotten that far. There was a small courtyard, a staircase, and a door under the stairs (locked, of course) that may well have led to the studio. Of course when it came to coming out again the door was not only locked, but the electrical mechanism for opening it was stuck! We pressed and pressed that button to no avail for a whole five minutes until it eventually did work.

Gouges, Roland and Grouchy all did a lot of walking around Paris, between 1789 and 1793. We tried to retrace their steps, sticking to the streets that dated from that period, and avoiding the new boulevards when we could. But come five o'clock we went for the metro (it was winter, after all!). When I came home I tried to replicate the map of the streets they would have walked, based on maps drawn around that time. The image above is a (poor) photograph of the map, with the places we visited listed at the top. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed