|

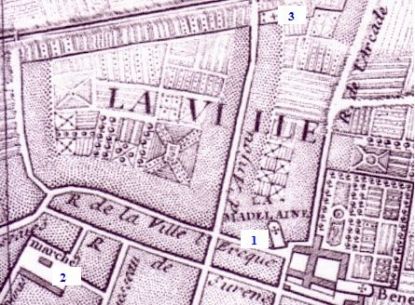

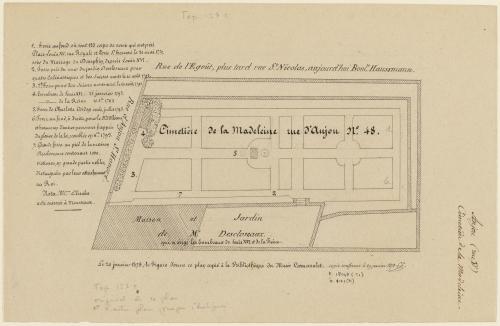

The revolutionary period, in particular the Terror, was hard on the Paris graveyards. Many people died in massacres and at the Guillotine who had to buried in the already full graveyards. When the body counts started to rise, the Parisians needed somewhere to pile up their dead. The site of the church of Sainte Madeleine, first opened in the 13thcentury was located roughly where 8 Boulevard Malherbes now stands. It had a very small cemetery and a slightly larger one was built in 1690, on land that was closer to the Faubourg Saint Honore, already a posh neighborhood. In 1720, the cure of la Madeleine sold a large tract of land to be convereted to a graveyard. The graveyard was built on a large rectangle of 45 by 19 meters surrounded by a wall. It filled up slowly at first, but in 1770 it received its first mass burial. On the occasion of the celebrations of the wedding of Louis the Dauphin and Marie-Antoinette, a show of fireworks was given to the people of Paris. This was a novelty, and more scary than exciting for many. There was a crush in the crowded streets and several hundred people died. These were buried in the Madeleine. The next large scale burial happened in August 1792, when the Paris revolutionaries, assisted by the Marseillais massacred the King’s Swiss Guards. Their mutilated bodies were thrown into the Fosse Commune at the Madeleine. By then it was summer, and the smell in the neighborhood became unbearable – someone reported it at the assembly, but it was decided that the risk of false rumours of a plague epidemic was too great if a fuss was made, and the subject was dropped. The rich inhabitants of the quartier would just have to put up with it. The location of the Madeleine was also very convenient for transporting bodies from the Place du Carousel and Place de la Revolution – the guillotine’s first two locations. Légende - Au recto, à gauche sur l'image, à l'encre, inscriptions correspondant à la numérotation de l'image : "1. Fosse au fond où sont 133 corps de ceux qui ont péri / Place Louis XV, rue Royale et Porte St. Honoré le 31 mai 1770, / soir du Mariage du Dauphin, depuis Louis XVI." ; "2. Fosse près du mur du jardin Descloseaux pour / quatre Ecclésisatiques et 500 Suisses morts le 10 août 1792." ; "3. 2e. Fosse pour 500 Suisses morts aussi le 10 août 1792" ; "4. Tombeau de Louis XVI. 21 janvier 1793. / -id- de la Reine 16 8bre 1793" ; "5. Fosse de Charlotte Corday seule, juillet 1793." ; "Fosse au fond, à droite, pour le Dc. d'Orléans / et beaucoup d'autres personnes frappées / du glaive de la loi ; comblée en Xbre. 1793." ; "7. Grande fosse au pied de la maison / Descloseaux contenant 1000. / victimes, en grande partie nobles, / distinguées par leur attachement / au Roi. / Nota. Mme. Elisabet / a été enterrée à Mousseaux.". Date et signature - Au recto, en bas à droite, à l'encre brune : "copie conforme le 29 janvier 1878 LL". - From the Musée Carnavalet. Eventually, in March 1794, the Madeleine was closed and the next victims of the Guillotine were buried elsewhere. But before then, more famous bodies were entered there, including the King and the Queen, many of their supporters and family members, Charlotte Corday – who benefitted from a single occupancy plot, the twenty-two Girondins (including Brissot) who died on 31 October 1793, and of course Manon Roland and Olympe de Gouges.

During the restoration, Louis XVIII built a chapel to the memory of his brother and sister in law. Small chapels were added later to commemorate the other victims of the Revolution.

0 Comments

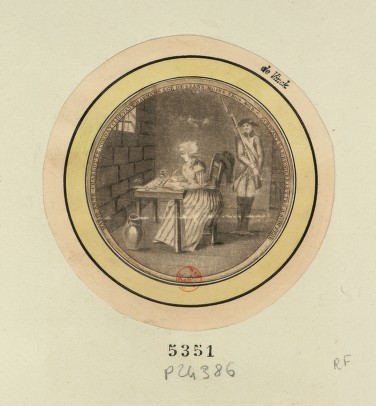

Charlotte Corday died at the guillotine in July 1793, a few weeks after Manon Roland’s arrest, and a few days after Olympe’s. Charlotte had come down from her native Vendee, in the north west of France, just below Britanny, to murder Jean-Paul Marat, the ‘friend of the people’ and leader, with Robespierre, of the Terror. She was an aristocrat, who left to her own devices, had ‘read everything’ in her parents’ library. She was a republican, who wanted to save the republic by ridding it of Marat, and not, as the English believed at the time, a royalist. She came to Paris, rang Marat’s door bell, was admitted to his bathroom where he was writing in the tub, to relieve a skin irritation, and she stabbed him. She was arrested immediately and tried very publically. A few days later she died. When we talk about women who were important actors in some historical event or other, very often there is a focus on what they looked like, in particular, whether they were pretty or not. (This, of course, does not simply apply to political women from the past but is still very much in force!) What's interesting about Corday's case, is that descriptions and portraits of her after she was caught are very different from earlier descriptions or portraits. Before the murder, Charlotte Corday was described as pretty, beautiful even, by all who saw her. Even Chabot, the Montagnard who thought her a horrifying accident of nature, and fancied he could detect plainly her criminal propensities painted on her face, still described her as having ‘spirit, grace, superb height and bearing,’ But the death of Marat changed the way she was perceived. Fabre d’Eglantine, actor and Danton’s private secretary, captured this reversal in his ‘Moral and physical portrait’ of Corday for the daily newspaper Le Moniteur Universel. “This woman who has been called very beautiful was not beautiful. […] she was a virago, fleshy and not fresh, without grace, dirty, as are nearly all female philosophers and blue stockings. Her face was covered in red patches, and featureless. Height and Youth are proof indeed! That is all it takes to be beautiful while on trial. Moreover this observation would not be needed if it were not for the general truth that any woman who is beautiful and knows it cares for life and fears death.” |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed