|

On 26 July 1789, Manon Roland wrote the following to her friend Louis-Augustin Bosc d'Antic: No, you are not free; no one is yet. The public trust has been betrayed. Letters are intercepted. You complain of my silence and yet I write with every post. It is true that I no longer offer up news of our personal affairs : but who is the traitor, nowadays, who has any other than those of the nation? It is true that I have written you more vigorously than you've acted. But if you are not careful, you will have done nothing but raise your shields. [...] Bosc d'Antic was a thirty year old botanist, who had just founded the first French Linnean society. But as a close friend of the Rolands, he was also a republican, and keen for France to change. In 1791, he became Secretary of the Jacobin's club. It is not clear what role he played before then. Manon Roland mentions 'his districts' - the old parishes, which under the Commune became 'Sections' - which leads one to suppose that he had been elected at the Assembly of June 89, sworn to give France a Constitution. His name does not feature, however, among the 300 Parisian members. Certainly, however, he and Roland's two other correspondents at the time, Lanthenas and Brissot, were active and influential. And they listened to her, asking for her advice and opinion on what to do. Brissot even published some of her letters in his new paper, Le Patriote Francois.

Clearly Manon was worried that the Revolution would peter out, because her friends did not act firmly enough. She was only just recovering from a life threatening illness, and still nursing her husband, so could not come to Paris herself to see to it that things were done properly. * The 'illustrious heads' she says must be tried are the king's brother and the king's wife, who were then believed guilty of a failed coup d'Etat. ** Decius, is Decimus Brutus, not the Emperor Decius. *** "You are f..." is in French "Vous etes f...". She no doubt wrote, or intended it to be read 'foutus', which means exactly what my translation suggests.

0 Comments

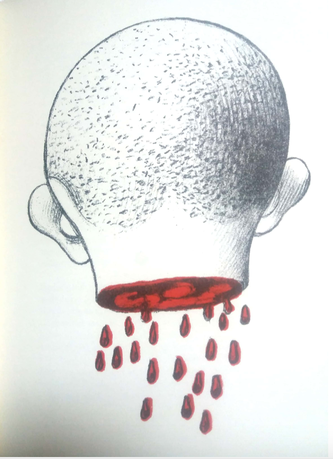

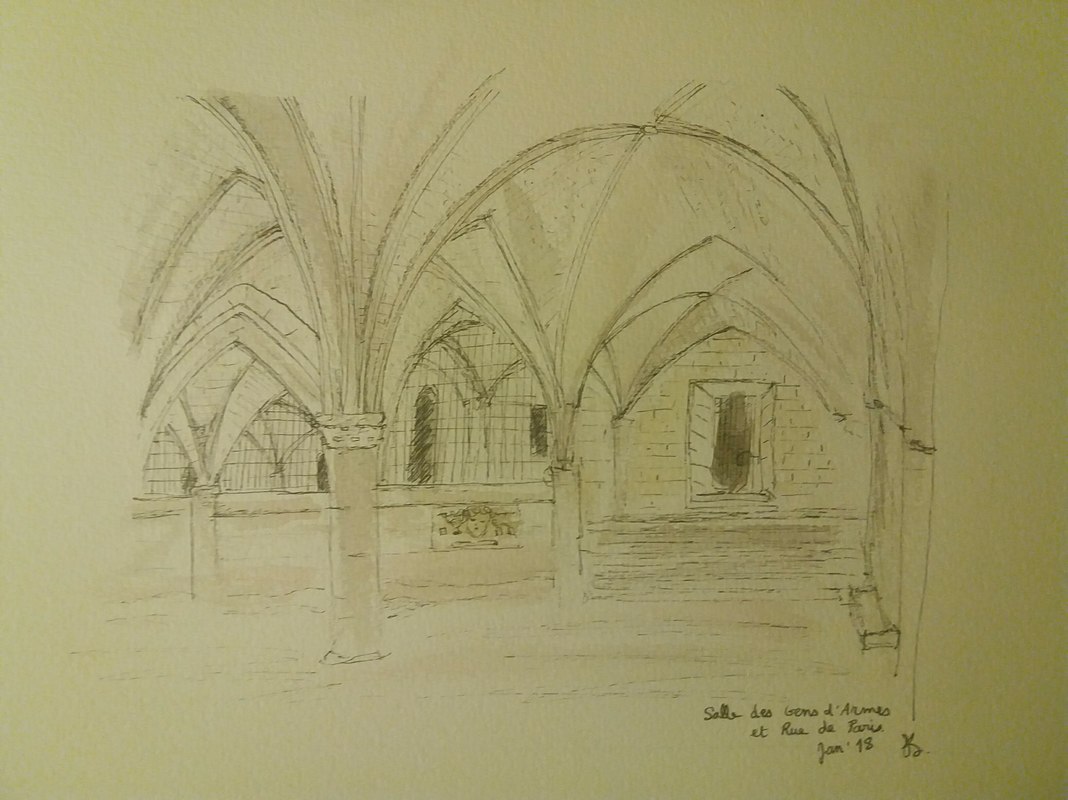

During a recent visit to the Conciergerie, I picked up a prettily bound book, entitled Note sur le supplice de la guillotine. The book contained a short essay of that title by Cabanis, five drawings by the artist Cueco, and a discussion of the moral and political philosophy of the guillotine by French philosopher Yannick Beaubatie. For the main part, Cabanis's article, written 1799 (an IV) argues against recent articles that claimed that the torment of the guillotine ought to be abolished because it cannot be proven that the guillotined do not feel pain. The articles (by members of the medical profession, Cabanis's own colleagues), cite as evidence witnesses's reports of decapitated heads moving in such a way as to suggest that they responded to the situation, and attempted to communicate. One example they cite is that of Charlotte Corday, whose decapitated head was slapped by one of Sanson's valets, after which it apparently reddened as if in shame and indignation. Cabanis answers that while he was not present at any decapitation (as he did not have the stomach for it) he was present at the testing of the machine and certifies that death must be instanteanous. He then goes on to discuss the philosophical question of where pain resides, and the medical phenomenon of bodily movement after death. At the end of the essay, Cabanis offers his moral and political reflections: the death penalty, he claims, ought to be abolished. But if it is not, the guillotine has to go. Not because it causes pain to its victim, but because it is too swift so that as a performance of a punishment it cannot serve its rightful purposes. Beaubatie takes this up in a fascinating discussion. In particular, he notes a resemblance between Cabanis' s reservations about the guillotine and Beccaria's utilitarian theory of punishment. Beaubatie notes further that Beccaria and Cabanis both frequented the Helvetius home, although two years apart. What Beaubatie does not note, however is the strong resemblance between Cabanis's thought and that of his sister in law and long term friend and collaborator Sophie de Grouchy. Cabanis's principal reason for thinking that the guillotine should not be used is not - as Beaubatie claims - that it cannot serve as an exemple or detterrent, but that it does not allow enough time for spectators to react emotionally in such a way that would help their sympathy grow. The guillotine’s work is done in less than a minute. That it did not occur to Beaubatie, in his commentary written in 2002, to look to his long term philosophical correspondent Sophie de Grouchy for influence, as well as to Beccaria (whose path with Cabanis crossed, but two years apart) is a sign of how much work has been done over the last fifteen years in recovering the works and influence of women philosophers. The gift shop of the Conciergerie is situated in a narrow room at the back of the largest medieval room in Europe, La Salle des Gendarmes. The narrow room is called Rue de Paris, after "Monsieur de Paris", an affectionate nickname for Charles0Henri Sanson, the executioner of the Revolution.

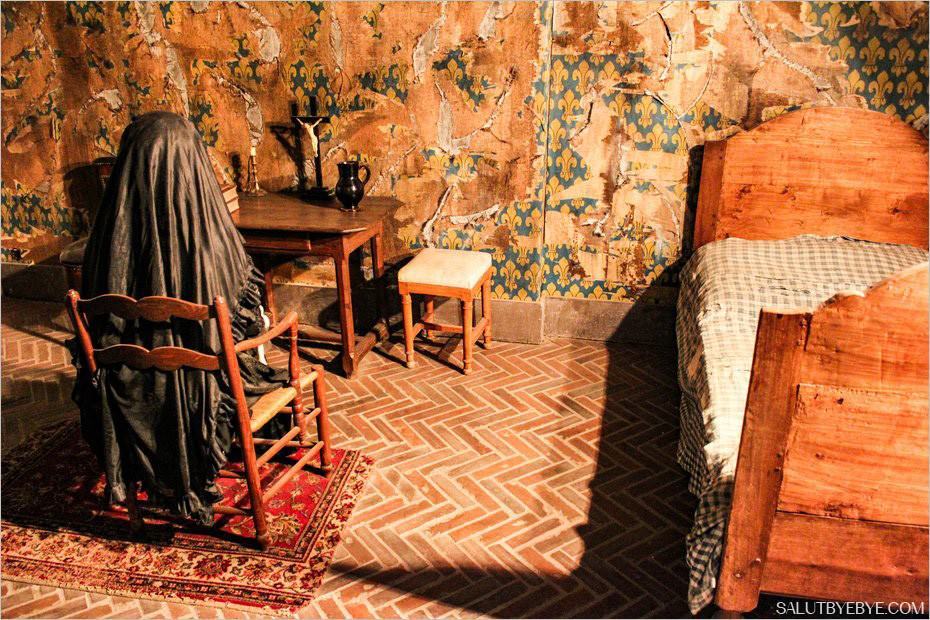

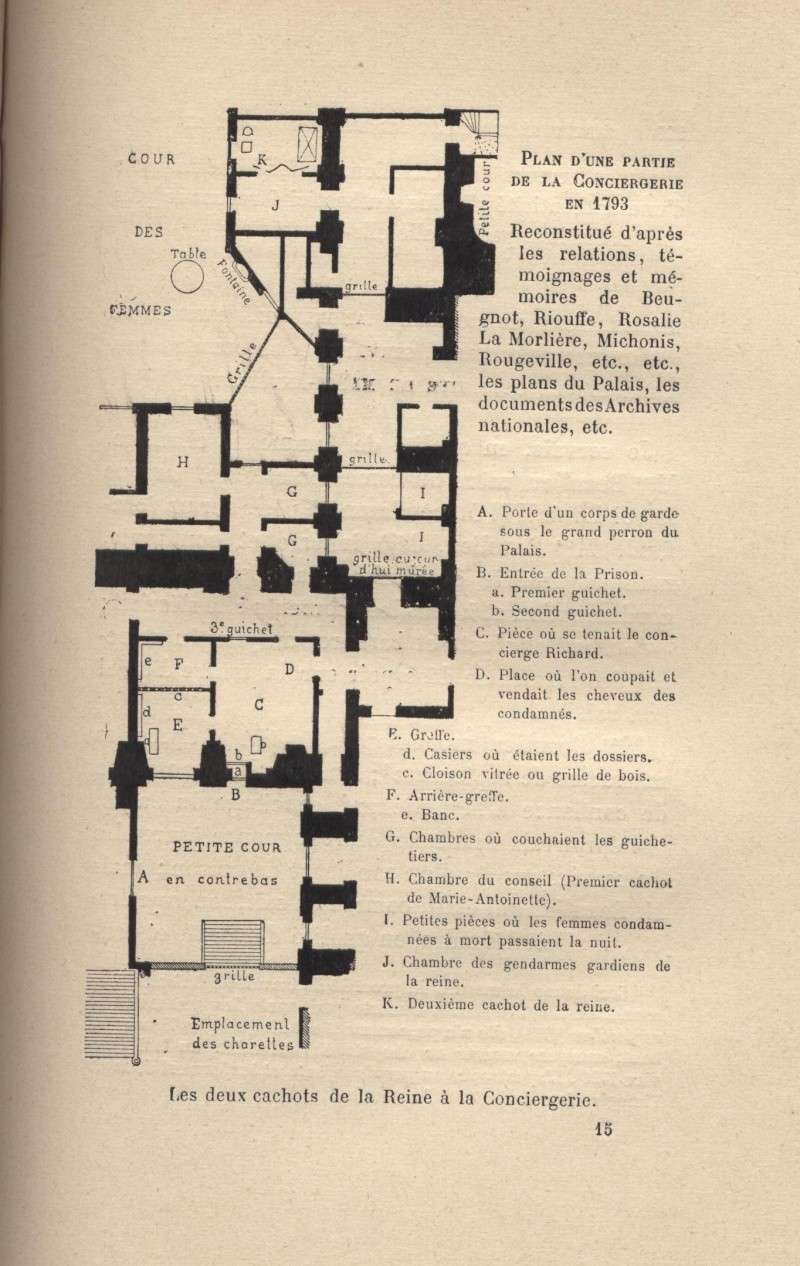

The Rue de Paris was what prisonners who could not afford to pay for a private cell walked through in order to reach the large room where they would stay until their trial along with hundreds of others. Private cells were called 'A la Pistole', because it cost a Pistole per night to stay there, a Pistole being a Louis d'Or, so a substantial amount of cash. Those who could not afford this were called 'Pailleux' because the room where they stayed was covered with (dirty) straw. Men and women were kept separately, and aside from Marie Antoinette's cell, and the women's courtyard, the Conciergerie has only reconstituted the living quarters of the male prisoners. This leaves us to speculate as to how women were accommodated. We know that Manon Roland was not rich, but yet she spent her last nights at the conciergerie on a bed - given her by another prisoner - rather than in the straw. On 2 November 1793, Olympe de Gouges was tried, and declared herself to be pregrant. She was examined by a team of two doctors and a midwife who found the signs to be inconclusive (it was too early to tell). She was executed the next day. Where did the examination take place? Either in her cell, which is reputed to have been the same as Marie-Antoinette's second cell, or in the infirmary. Marie-Antoinette was moved from one cell to another when she attempted to escape through a trap door, on her way between her first cell and the women's courtyard. The second cell was isolated from the others. A wall was built to cut it in half and guards were posted in the other half to prevent any further attempted rescue. This was the cell Olympe was taken to, as she had to be kept 'au secret', unable to communicate with anyone who might have taken a letter to her friend Cubiere (who could still have saved her, perhaps). Because this cell was Marie Antoinette's it was preserved. But the rest of that floor was transformed, in part for Louis XVIII to build a chapel in Marie-Antoinette's memory. The infirmary no longer exists, but it was described by one of the inmates of the prison, Le Conte de Beugnot as a long room, 25 by 100 pieds (around 8 by 32 meters), with a vaulted roof, grilles on both sides and illuminated by two narrow windows. Looking through old maps and descriptions tells us very little as to where the infirmary might have been, except that it was supposedly just outside of Marie Antoinette's cell. Still, I decided that I knew the Conciergerie well enough to have a shot at finding traces of the infirmary. For one thing, I knew where there was a narrow window that was close to Marie-Antoinette's second cell. The turett was clearly part of the 19th century building, but it seemed as though the window below it may have existed in a previous incarnation of the first floor. So off I went with my team of investigators - my daughter, who'd already participated in the Revolutionary Paris tour and helped research this post ; my mother, who's often finding information for me, my son, whose first visit to the Conciergie this was, and who was mostly extremely patient, and my nephew, whose excellent detecting skills proved to be invaluable Although the Conciergerie is one of my favourite buildings in Paris and one I know well, I don't think I had noticed until now how much of it was recent. Despite its looming medieval towers, and the large medieval room, most of it dates from the 19th century, and very little remains of the revolutionary period. This may be because a lot of the cells were constructed during the revolution, in a hurry, in order to accommodate the increasing number of prisoners. The first thing we noticed was that the building of the chapel had meant the destruction not only of the floor it was on, but that part of the top floor was also missing. Marie Antoinette's cell itself was clearly marked out as older, with a brick floor, slightly lower than the floor of the chapel. This was where the infirmary supposedly begun. But where did it go? We walked out to the women's courtyard, where women went to walk, and talk, and wash their clothes in the fountain. The turret where I'd seen the narrow window was on the wrong side, i.e. near the Palais de Justice and not apparently connected to the building where Marie Antoinette's Cell was. After some walking around and a fruitless attempt to question a man who worked in the museum (what? he did not know the entire, precise history of the building?!) the children worked out that there must have been another turret, roughly opposite the existing one, and at a place where the infirmary would have passed. We still have but a very vague view of where this place was. But at least we've had a shot at reconstructing it. More importantly, perhaps, we came out with a much stronger understanding of how elusive the past is, even when it is set in stone. The ghosts of the revolution may still walk the corridors of the Conciergerie, but these are not the same corridors that we walk as tourists.

Every year for Christmas and New Year we dread the loss of the celebrities we love, and reminisce those who died during the year. Apparently it was very much the same in Eighteenth century France, if Manon's letters are anything to go by. On 2 January 1777, she wrote to her friend Sophie Cannet: Rousseau is not dead. He did not take a fall, as it was reported, and was not even even ill. I would have been annoyed had he disappeared before I got to see him. Were it not for certain troubles I cannot seem to shake, there are some things I might try, I would not write, as his wife refuses to accept that I am the author of my own letters, but... but... I must leave such projects to a later time. Unfortunately Manon never got to put these plans into action as Rousseau did die a year and a half later. On 6 July 1778, she sent the news to Sophie's sister, Henriette: Jean-Jacques is dead. I was given the news yesterday at dinner. Immediately, I felt my appetite disappear, my stomach tighten and heave at the thought of eating anything. Why? ... The best of Rousseau stays with us; anything else is but released from pain. His life is filled, his spirit and his sentiments are still here, so why am I so saddened? |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed