|

One of Olympe de Gouges’s role model was Madame d’Eon. Another was Ninon de L’Enclos, philosopher and courtesan of the seventeenth century. L’Enclos was an Epicurean philosopher. In a letter to Saint-Evremont, she wrote: It would be useless to press the arguments, repeated a hundred times by the Epicureans, that the love of pleasure and the abolition of pain are the primary and most natural inclinations noticed in all people. Wealth, power, honor, and virtue contribute to our happiness, but the enjoyment of pleasure, let us call it voluptuousness, to sum up everything in a word, is the true aim and purpose to which all human acts are inclined. (Letter to the modern Leontium) She developed her philosophy in her correspondence with Saint-Evremont and the Marquis de Sevigne. She offered a naturalistic and mechanistic metaphysics, ethics and theory of love. In an unsigned 1659 pamphlet, The Coquette Avenged, she argued that one could be virtuous without the help of the church. This view caused as much scandal if not more as her lovers. Recent biographers, such as Martial Debriffe, Ninon de Lenclos; La belle insoumise. (Paris: France-Empire, 2002) have begun to give Ninon the place she deserves as a philosopher and as a proto-feminist. But as far as the 19thcentury her reputation was divided. Male historians regarded her almost universally as a courtesan first, a libertine, who scandalized France by taking as many lovers as a man in her position would have. So when Olympe claims her as a model, these same historians understand that she wanted to make her fortune as a high class prostitute: With her love of adventure she was soon thrown in a whirlwind of romantic intrigues. She became the soul of all the epicurean clubs, and claimed the honour of being called the Ninon of the 18thcentury. She could have succeeded in achieving the same notoriety, says M. Desessarts in his Proces de la Revolution, if her most fiery and impetuous passions had not caused her to wither early.” There’s a common fallacy here, which comes of judging a woman’s ambitions through a man’s gaze. Olympe did not wish to be like Ninon because men saw her as a beautiful prostitute! Olympe, they say, became a writer because she no longer looked good enough to be a courtesan. But what these historians fail to see, blinded by Ninon’s sexual reputation, is that Ninon was all along a talented author, and that this is clearly what attracted Olympe’s attention. Her 1788 play Moliere chez Ninon, gives us a better idea of what it was Olympe saw in Ninon, aside from the fact that she was a daring author. Mlle LE ROI - She does not dissimulate enough, nor is she hypocritical enough, to hide her way of life from us, she does not make of us her confidants yet she is unconcerned by what we may perceive. The phrase ‘a good man in the guise of a woman’ recalls Olympe’s admiration of Madame d’Eon, the 18thcentury trans-woman who fought and won duels in London. But the qualities of honesty, and straightforwardness, the lack of concern for gossip and the ability to relate to all, regardless of class are almost certainly also what Olympe admired and sought to emulate. Many of her writings enjoin the readers to take her as she is, and warn them that she will not pretend to be otherwise than nature has made her.

0 Comments

If women philosophers of the 17thcentury are occasionally brushed off as being not ‘proper philosophers’, but ‘learned maids’ , those of the 18thcentury, at least in France, were from the earliest records, classified as salonières. So Madame de Stael, the author of 30 published works, novels, plays, philosophical and political reflections is best known for the fact that she held a salon in which famous men came to talk. In fact, her output was a little bigger than that of her lover and most famous associate, Benjamin Constant. As to the difference in quality – who knows? Until recently her works have not been studied by philosophers, whereas Constant’s have. A look at Jules Michelet’s Women of the Revolution (1855) shows what the implications of calling women salonières were. This volume is comprised of portraits that Michelet had sketched in his History of the French Revolution (1847-1853, 9 volumes). Sophie de Grouchy is described as a Salonière, a beautiful woman who was skilled at entertaining republicans, and who, moreover, was the dutiful wife of one of the revolution’s greatest intellectual, Condorcet. One senses that Michelet thinks we should be grateful that she looked after this national genius, and enabled him to shape the future of the republic. But to him she was no more than that. Manon Roland, a ‘femme de coeur’ is given an example of womanly republican virtue. She is just as Rousseau wanted women to be – domestic, ruled by their heart, and entirely given to nurturing the virtues of the republic in their family. But Manon, Michelet adds, is rather more muscular and less ethereal than Rousseau’s Julie, for instance. And when she sees that being nurturing and domestic is no longer enough, she acts – she exerts her political influence through her salon. Michelet does not mention Olympe’s salon, and does not seem to be aware of it, picturing her in crowds, among the women of the people and making much of her supposed ignorance: “She was quite illiterate.” He wrote. “It was even said that she could neither read nor write at all.” However noble he may have thought her, this is what stands out. Olympe, the writer, could not read or write. But the most telling chapter in Michelet’s book is not on individual salons, or famous women, but on the moral downfall of the Girondins. This is towards the end of the volume, whereas the more flattering descriptions of individual women are closer to the beginning. In 1793, Michelet said, the Girondins were giving in either to suicide or to depravation: gambling, and orgies. Many women, whether professional prostitutes or milliners were involved. But it was not just the lowly prostitutes who finished off the brave Girondins. Michelet goes on to elaborate on the way women can and did cause the downfall of men. “women, especially, and even the best, in such a case, exert a dangerous influence to which there is no resistance. They influence by their graces, but still more often by the touching interest they inspire, by their frights which they wish calmed, and from the happiness they really feel at receiving support from you. […] These ladies were very skillful, being careful not to show the after-thought. The day, good, moderate, and mild republicans would be seen in their salons. The second day, Feuillants and Fayettists would be presented to you.” And before you knew it, he continues, the charming salonist had turned your royalist. And even ‘true love’ Michelet continues, contributed to the downfall of the Gironde: “The love of Mademoiselle Candeille was conducive to the destruction of Vergniaud. This pre-occupation of the heart increased his indecision and his natural indolence. It was said that his mind seemed to be wandering elsewhere, and they were right. This mind, at a time when the country should have claimed it entirely, inhabited another soul.” Julie Candeille was a successful composer and famous actress – who had taken on the role of Mirza in Olympe de Gouge’s abolitionist play. Her acting career ended in 1798 and she concentrated on music till her death in 1834. Pierre Victurnien Vergniaud was an orator for the Gironde. He was the last of the 22 Girodins to be executed on 31 October 1793.

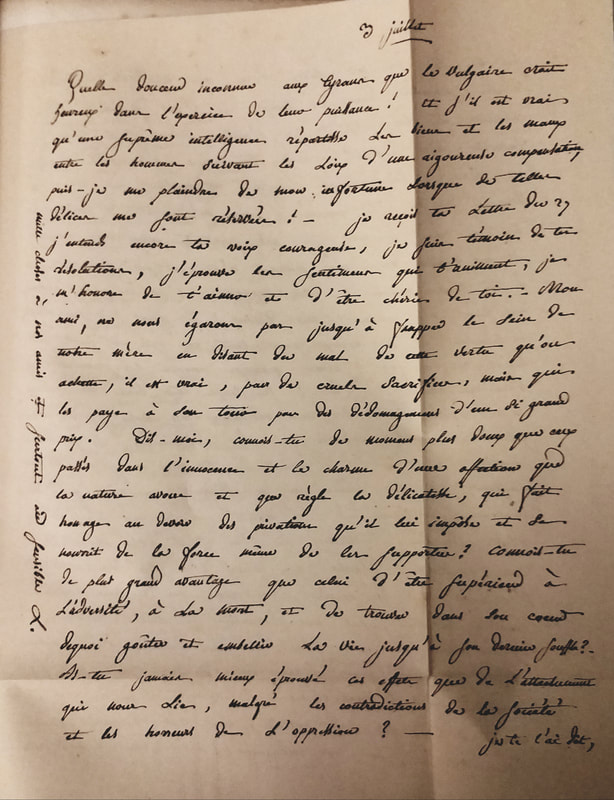

The text below is extracted from Manon Roland’s second letter to her lover Buzot, on 3 July 1793, from the prison of Sainte Pélagie. Do you know a greater advantage than that of being superior to adversity, to death, et to find in one’s heart the means to enjoy and embellish life until one’s last breath? – Have you ever felt these effects from the attachment that ties us together, in spite of all the contradictions of society, and the horrors of oppression? – I told you so: this is why I enjoy my captivity. – I am proud to be persecuted in those times where good character and honesty is proscribed, and even without you, I would have born it with dignity; but with you, it becomes sweet, and dear. The villains think to hurt me by putting me in irons… Insane! What do I care whether I live here or there? Don’t I go everywhere with my heart, and isn’t my constriction me in a cell meant that I am his entirely? […] The rest of the letter casts some light on how she dealt with the fact that she was still married and that her husband, Jean-Marie Roland, was broken-hearted by her emotional desertion. She describes her state of mind when she was arrested: I won’t say I went out of my way to meet them (the men who came to arrest her), but it is very true that I did not run from them. I did not stop to think whether their fury would extend to me, but I thought that if it did, it would give me an occasion to serve X (Roland) through my statements, my constancy and firmness. I delighted in finding a way of being useful to him while at the same time being yours more completely. I would like to sacrifice my life to him in order to earn the right to breathe my last breath for you alone. Except for the terrible unrest when I learnt of the decree against the proscribed, I have never enjoyed such great calm than in this strange situation, and more completely once I learned that nearly all were safe, and once I saw that you were working in freedom to liberty at preserving that of your country. Vincent Ogé was a wealthy man of colour from Saint Domingue, a quarteron, in the terminology of the times. He found himself in Paris in 1789, and decided to stay after meeting first with Julien Raimond, and like him becoming a member of the Societé des Amis des Noirs. The Society, lead by Brissot, had previously been campaigning for abolitionism. However, they decided to support first the claim of men of colours to full political rights. Ogé and Raimond together petitioned the Assembly, but failed to convince it. With Brissot’s approval, Ogé decided that the next step was rebellion.

he travelled first to England, where her received support from Clarkson, then to Louisiana, where he is said to have purchased fire arms, and finally back to Haiti, where he led 300 men in a revolt. The revolt was quashed in less than a month. Ogé died on the wheel on 6 February 1791. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed