|

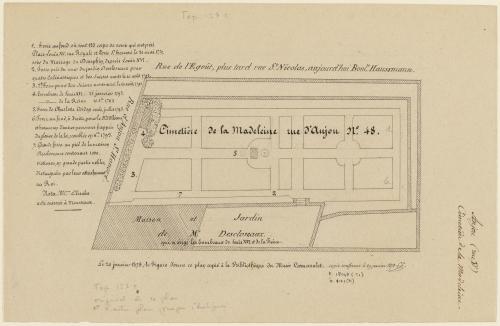

The revolutionary period, in particular the Terror, was hard on the Paris graveyards. Many people died in massacres and at the Guillotine who had to buried in the already full graveyards. When the body counts started to rise, the Parisians needed somewhere to pile up their dead. The site of the church of Sainte Madeleine, first opened in the 13thcentury was located roughly where 8 Boulevard Malherbes now stands. It had a very small cemetery and a slightly larger one was built in 1690, on land that was closer to the Faubourg Saint Honore, already a posh neighborhood. In 1720, the cure of la Madeleine sold a large tract of land to be convereted to a graveyard. The graveyard was built on a large rectangle of 45 by 19 meters surrounded by a wall. It filled up slowly at first, but in 1770 it received its first mass burial. On the occasion of the celebrations of the wedding of Louis the Dauphin and Marie-Antoinette, a show of fireworks was given to the people of Paris. This was a novelty, and more scary than exciting for many. There was a crush in the crowded streets and several hundred people died. These were buried in the Madeleine. The next large scale burial happened in August 1792, when the Paris revolutionaries, assisted by the Marseillais massacred the King’s Swiss Guards. Their mutilated bodies were thrown into the Fosse Commune at the Madeleine. By then it was summer, and the smell in the neighborhood became unbearable – someone reported it at the assembly, but it was decided that the risk of false rumours of a plague epidemic was too great if a fuss was made, and the subject was dropped. The rich inhabitants of the quartier would just have to put up with it. The location of the Madeleine was also very convenient for transporting bodies from the Place du Carousel and Place de la Revolution – the guillotine’s first two locations. Légende - Au recto, à gauche sur l'image, à l'encre, inscriptions correspondant à la numérotation de l'image : "1. Fosse au fond où sont 133 corps de ceux qui ont péri / Place Louis XV, rue Royale et Porte St. Honoré le 31 mai 1770, / soir du Mariage du Dauphin, depuis Louis XVI." ; "2. Fosse près du mur du jardin Descloseaux pour / quatre Ecclésisatiques et 500 Suisses morts le 10 août 1792." ; "3. 2e. Fosse pour 500 Suisses morts aussi le 10 août 1792" ; "4. Tombeau de Louis XVI. 21 janvier 1793. / -id- de la Reine 16 8bre 1793" ; "5. Fosse de Charlotte Corday seule, juillet 1793." ; "Fosse au fond, à droite, pour le Dc. d'Orléans / et beaucoup d'autres personnes frappées / du glaive de la loi ; comblée en Xbre. 1793." ; "7. Grande fosse au pied de la maison / Descloseaux contenant 1000. / victimes, en grande partie nobles, / distinguées par leur attachement / au Roi. / Nota. Mme. Elisabet / a été enterrée à Mousseaux.". Date et signature - Au recto, en bas à droite, à l'encre brune : "copie conforme le 29 janvier 1878 LL". - From the Musée Carnavalet. Eventually, in March 1794, the Madeleine was closed and the next victims of the Guillotine were buried elsewhere. But before then, more famous bodies were entered there, including the King and the Queen, many of their supporters and family members, Charlotte Corday – who benefitted from a single occupancy plot, the twenty-two Girondins (including Brissot) who died on 31 October 1793, and of course Manon Roland and Olympe de Gouges.

During the restoration, Louis XVIII built a chapel to the memory of his brother and sister in law. Small chapels were added later to commemorate the other victims of the Revolution.

0 Comments

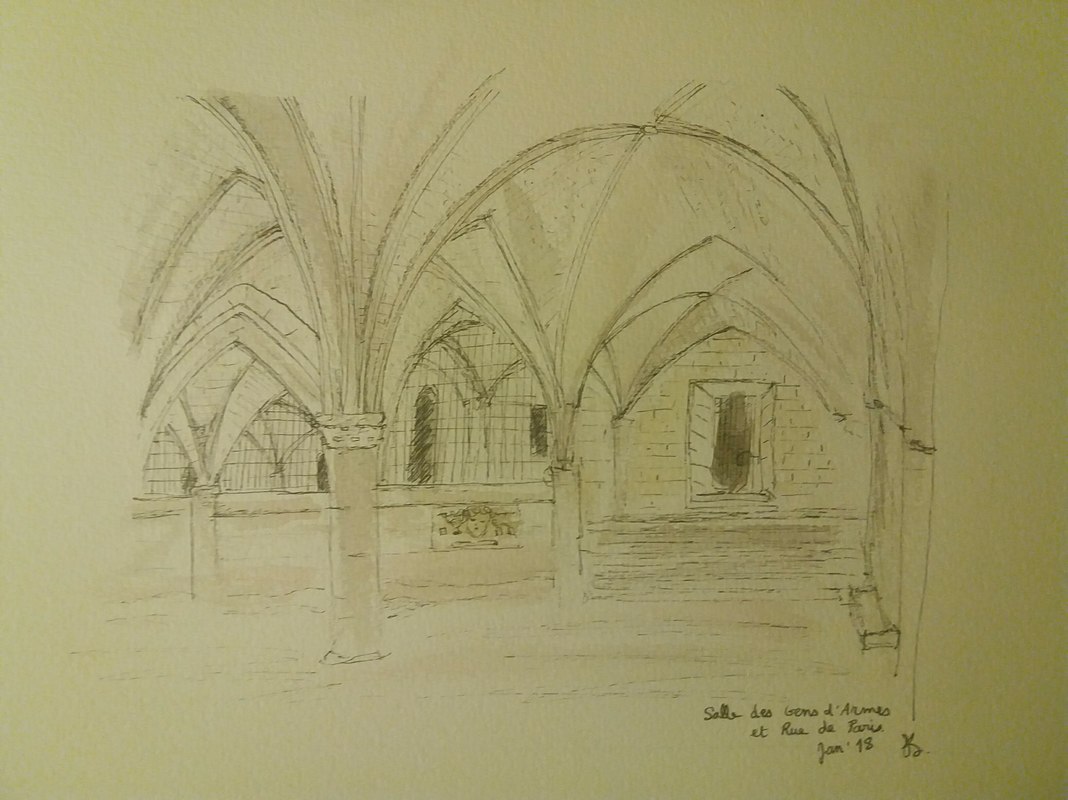

The gift shop of the Conciergerie is situated in a narrow room at the back of the largest medieval room in Europe, La Salle des Gendarmes. The narrow room is called Rue de Paris, after "Monsieur de Paris", an affectionate nickname for Charles0Henri Sanson, the executioner of the Revolution.

The Rue de Paris was what prisonners who could not afford to pay for a private cell walked through in order to reach the large room where they would stay until their trial along with hundreds of others. Private cells were called 'A la Pistole', because it cost a Pistole per night to stay there, a Pistole being a Louis d'Or, so a substantial amount of cash. Those who could not afford this were called 'Pailleux' because the room where they stayed was covered with (dirty) straw. Men and women were kept separately, and aside from Marie Antoinette's cell, and the women's courtyard, the Conciergerie has only reconstituted the living quarters of the male prisoners. This leaves us to speculate as to how women were accommodated. We know that Manon Roland was not rich, but yet she spent her last nights at the conciergerie on a bed - given her by another prisoner - rather than in the straw.  Cities don't stay still. Their shapes change. Rivers move, neighborhoods are destroyed to make way for new roads, and buildings fall down and are replaced with little or no respect for the people that once lived there, or the things they said and did. Paris underwent a great deal of change in the 19th century. In 1853, Napoleon III commissioned his prefect, Haussmann, to redesign Paris so that it would be beautiful, united and airy. The old Paris was dirty and unhealthy - there were too many people living in confined spaces, and a lot of sickness and death. But it was also easier to ferment revolt in dark and narrow streets. In June 1832 and May 1848, the streets of Paris had been the scene of much fighting, with barricades being set up in the narrow passages, piles of furniture and debris, upturned paving stones. This would no longer be possible in Haussman's wide boulevards. Haussman worked on the Rive Droite first. But his most drastic redesign was perhaps the Ile de la Cite, where the Conciergerie, the last prison of those who were executed in the Revolution, stands. Between 1859 and 1867 the Capital was transformed from a nest of narrow breeding disease and discontent, to a network of large, airy boulevards, connected by the remaining truncated streets.

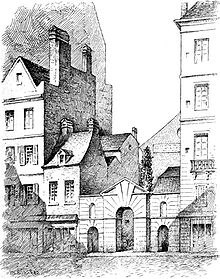

The first boulevard constructed was the Rue de Rivoli, lounging the Seine river on the Rive Droite. This is by far the fasted way from the Conciergerie, on the Ile de la Cite, to the place de la Concorde, previously Place de la Revolution. In other words, had this road existed in 1793, Manon Roland and Olympe de Gouges would have had a much more comfortable journey from their prison to the guillotine. In 1870, Haussman was dismissed. The Parisians had had enough of their city being constantly turned upside down, and his projects were expensive. Nonetheless, they were continued until 1927. And seven years after Haussman's dismissal, the Boulevard St Germain was constructed. Many buildings were taken down in order to make space for this, including the prison where Manon Roland was first taken, L'Abbaye. The space where the prison building once stood is now occupied by a restaurant from a chain specialising in Belgian mussels. Just as Olympe de Gouges did, Sophie de Grouchy had to relocate to the suburbs during the Terror. In 1793, the Jacobin Chabot had issued an order to arrest her husband, Condorcet. Condorcet had gone into hiding in the house of Madame Vernet, on the Rue des Fossoyeurs (now the Rue Servandoni). Their property was confiscated by the government, and Sophie, together with her young daughter, her nanny and her sister Charlotte, moved to a house on the Grande Rue D'Auteuil, not far from where Madame Helvetius lived. Several times a week, Sophie walked into Paris to visit her husband. As she did not want to be recognised, or to attract anybody's attention to Condorcet's hiding place, she came dressed as a peasant woman, pretending to be with the crowds of farmers come to sell their goods to the starving capital. Once through the gates, she would lose herself in the crowds come to see that day's executions at the Place de la Revolution (now Place de la Concorde), then cross the river to reach the left bank, and walked towards the church of St Sulpice, and beyond that to the street where her husband was hiding. Often she would bring him books, or notes that he needed for his work - as he'd had to leave home in a hurry. She would also stay and encourage him, and work with him. His last work, the Sketch of human progress, was almost certainly something they worked on together. After seeing her husband, Sophie would walk back across the Seine towards the Rue St Honoré, where she rented an underwear shop and the half-floor above it. Putting Auguste Cardot, younger brother of her husband's secretary, in charge of the shop, she set up a studio in the alcove and worked on her miniatures from there. Thus she insured that she had sufficient income to see to the needs of her husband, her family and herself until she could claim back some of what the government had seized.

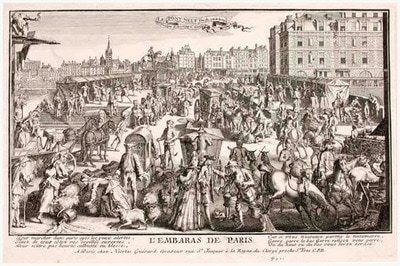

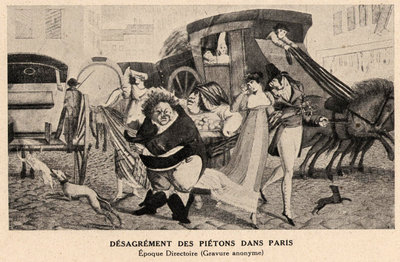

By the time the Terror kicked in, living in Paris was no longer a safe option for those who'd been at all involved with the opposition party and many retired to the nearby countryside. One very popular place was Auteuil, where Madame Helvetius ran her famous salon where philosophers, mathematicians, poets and politicians gathered. Both Sophie de Grouchy Olympe de Gouges moved there. But of course one still had business in Paris. Olympe had to travel there to visit her printer, and make sure her latest tracts were pasted and distributed where she wanted them to be. This meant first getting to Paris, and then through the busy streets to her printer's in the 6th arrondissement. This is Olympe's own description of one particular trip to Paris from Auteuil:

I live in the countryside. I left Auteuil this morning at eight and winded my way to the road that goes from Paris to Versailles where one can often find those famous roadside cafés that inexpensively gather passers by. No doubt an unlucky star was pursuing me that morning. I reached the gate and I could not even find the sad, privileged, hackney coach. I rested on the steps of that insolent edifice that secreted clerks. Nine o’clock chimed and I continued on my way; I spotted a coach, took my place, and arrived at a quarter past nine, according to two different watches, at the Pont-Royal. I took the hackney coach and flew to my printer, rue Christine, for I could only go so early in the morning: when I am proofreading there is always something to do, if the pages are not too tight or too full. On 30 December last year, I took a walk in Paris with my daughter and her friend, to identify some of the places where Olympe de Gouges, Manon Roland and Sophie de Grouchy had lived or worked. We found very few actual buildings as many were destroyed when Paris was redesigned in the 19th century. We did find, however, the building on the Faubourg St Honore where Sophie de Grouchy set up her studio in 1793, when her husband, Condorcet was in hiding on the Rue des Fossoyeurs (we also found this building). Someone was entering the St Honore building, so we decided to sneak in behind them. We looked around, finding little of interest, Were we expecting discarded paint brushes or watercolour stains? But we were very pleased to have gotten that far. There was a small courtyard, a staircase, and a door under the stairs (locked, of course) that may well have led to the studio. Of course when it came to coming out again the door was not only locked, but the electrical mechanism for opening it was stuck! We pressed and pressed that button to no avail for a whole five minutes until it eventually did work.

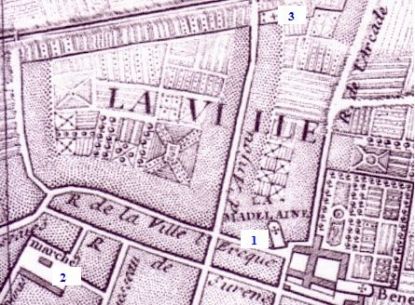

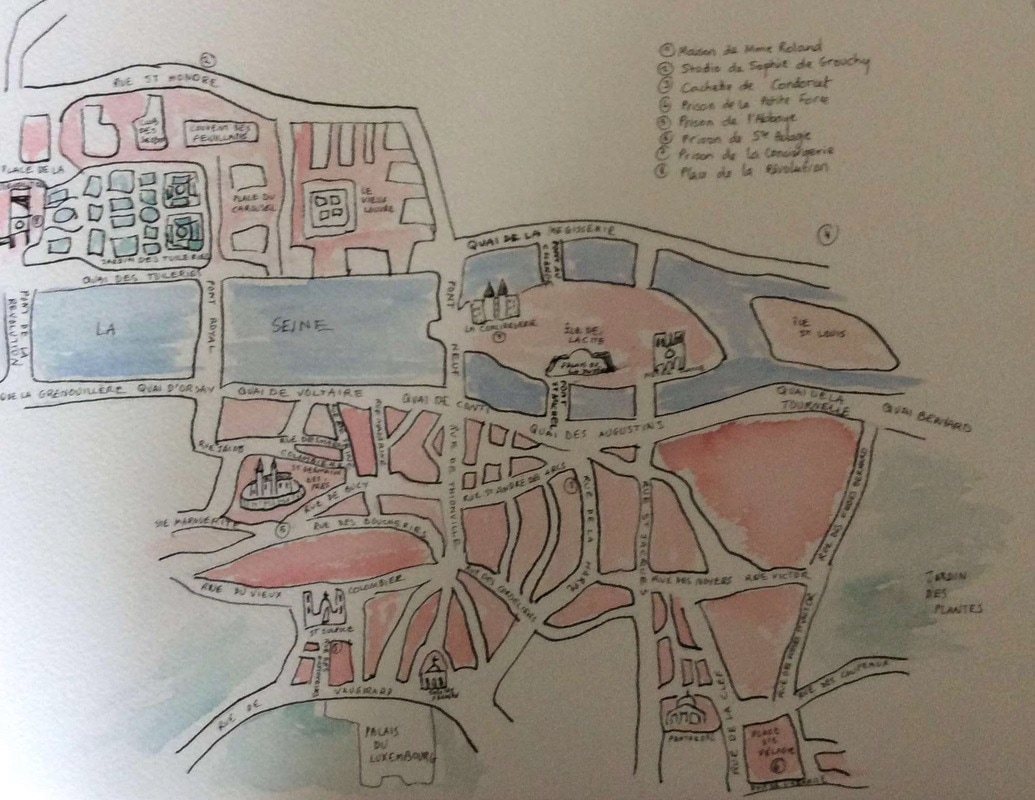

Gouges, Roland and Grouchy all did a lot of walking around Paris, between 1789 and 1793. We tried to retrace their steps, sticking to the streets that dated from that period, and avoiding the new boulevards when we could. But come five o'clock we went for the metro (it was winter, after all!). When I came home I tried to replicate the map of the streets they would have walked, based on maps drawn around that time. The image above is a (poor) photograph of the map, with the places we visited listed at the top. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed