|

Manon Roland did not live through a pandemic. But she did spend several months in forced isolation, when she was arrested and sent to prison, first at l'Abbaye, then at Sainte Pelagie. Did her experience bear any resemblance to ours, who have to self-isolate at home while Covid19 weakens and hopefully goes away? Certainly there are many points in common: Fearing for her friends' lives – check: those of them who were not also in prison were running, and in fact many of them died. Fearing for her own – check: and quite rightly too, as she was guillotined after 5 months of prison. Having to stay away from her loved ones to protect them – check: the motive for her arrest was that she might give away the whereabouts of her husband and other Girondins, including her lover Buzot, so she had to make sure that she kept her contacts with them very discreet indeed. Being confined to a small indoor space, without all her work stuff – check: Though her first cell was fairly comfortable, she was moved somewhere smaller. And though she had some books sent to her, and was able to buy pens and papers, most of things were inaccessible under seals. Knowing the world around her was falling to pieces because its leaders were mad and not having a clear idea of when it would all be over – check: she saw the Terror as the death of the Revolution and did not think the republic would ever recover. How did Manon cope with isolation? Not being ill, and being completely isolated from anyone she may have had to care for or homeschool, such as her daughter, Eudora, she could use the time pretty much at her own discretion: I plan to use the leisure of my captivity by retracing my personal life from my earliest childhood until now. To go back thus, on every step of one's career is to live a second time. And what better is there to do in prison than to take one's existence elsewhere through a happy fiction or interesting memories? How did she manage to settle down to work in such circumstances? Manon tells us that her education, which mixed Plutarch with omelet making, and dancing lessons with Latin was an ideal way of preparing for a varied life, and especially useful for knowing how to make the best of a very unpleasant situation: This mixture of serious study, pleasant exercise and ordered domestic tasks, seasoned by mother's wisdom, rendered me fit for everything. This seemed to predict the vicissitudes of my fortune and helped me bear them. [...] I am nowhere out of place. So when she first arrived at l'Abbaye, her first prison, she immediately set about to organize herself, so that she would be comfortable and able to work: Up at noon, I examined how I would settle in my new home. I covered a small and mean table with a white cloth and placed it under the window, intending to use it as a desk, resolved to eat at the corner of the hearth in order to keep my work space clean and tidy. But before you ask yourself how you could be more like Manon, and make your quarantine more productive and tidier at the same time, remember that Manon died at the guillotine. Don't be like Manon. Stay safe.

0 Comments

In her Memoirs Manon Roland questions the idea that it is wrong that women should serve as their husband's official secretaries. It is natural that husband and wife should work together she says. It is better for a woman to use her skills and intelligence drafting political pamphlets and letters than intriguing in her salon. Unfortunately, the other Jacobins did think that Roland was intriguing in her salon as well as drafting documents, and that the documents she drafted she did so in secret. Marat called her study a 'boudoir', suggesting that it was the entrance to her private quarters, where she entertained male visitors. The boudoir (a sort of sitting/dressing room, sometimes with a writing desk) was a boundary between the public and the private domain. While a 'salon' was a room used for entertaining visitors, and was as such very public, especially in the home of politically active people, the boudoir was more private and could only receive personal and close friends. But is was not as private as the bedroom, where only family and lovers could be entertained. The Marquis de Sade exploited this ambiguity of the boudoir in one of his books – La Philosophie dans le boudoir (sometimes badly translated as Philosophy in the Bedroom), the boudoir being the place where we can both debate public ideas, and perform private acts.

While we continue to investigate the lives, deeds and works of the great women of the French Revolution, let's not forget that some of these women were married, and that their husbands sometimes also contributed to the political events of their times. This is not, sadly always the case, and sometimes, what we have are rather petty disputes between men who were not as good at their jobs or deserving of their honour as they might have been!

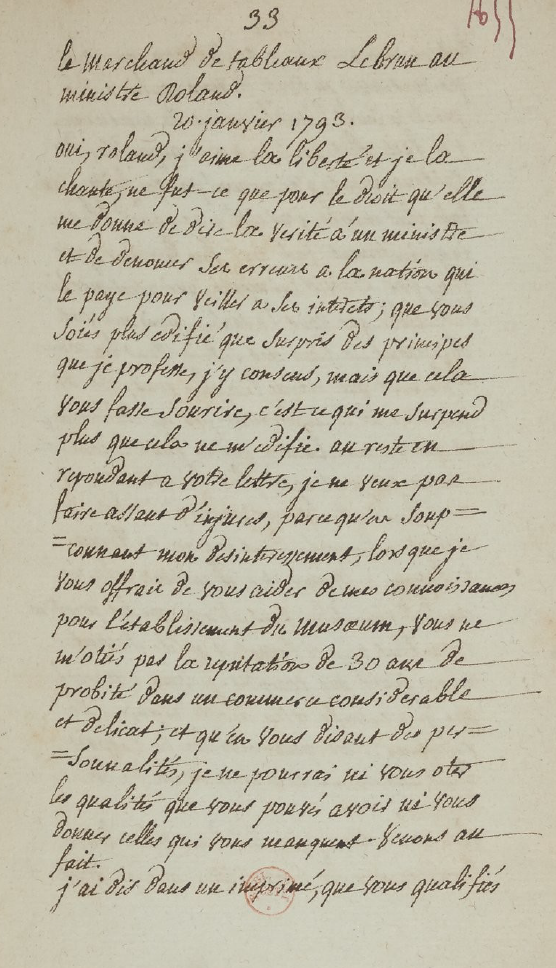

This is partly true of an exchange between Jean-Marie Roland, Manon's husband, and Charles Lebrun, husband to the celebrated painter Elizabeth Vigee-Lebrun. Lebrun was an ambitious art-dealer, supported entirely by his successful wife's earnings and works. However, Vigee Lebrun, who was Marie Antoinette's favorite portraitist, had gone into exile in the early days of the revolution. When she left, she took only 80 louis with her and left most of her fortune with her husband. While abroad she worked and continued to send her some of her substantial earnings to Charles. In order for that money not to be confiscated, Charles asked for a divorce – this was on paper only, and married life resumed as soon as she returned from her 12 year exile. Jean-Marie Roland was minister of the interior – but we know that a lot of his decisions were made by his wife, and that she wrote several influential letters for him. The two husbands came to fight over the question of how to look after the art confiscated from the aristocrats and the clergy. Lebrun thought he should be given the job and paid handsomely to do it. Roland thought this was not a priority. Lebrun published a pamphlet which Roland found insulting and even threatening, and Lebrun responded with an epistolary meltdown, accusing Roland of not being a true republican. I owe the details of this story to Bette W. Oliver's book, Surviving the French Revolution (chapter 4). Here is the first page of Lebrun's letter below, courtesy of Gallica When Manon Roland was at the prison of Sainte Pelagie, she found at first the company a bit too loud for her tastes: the prison was full of prostitutes and thieves whose ribald jokes she could hear through the thin walls of her cell. So when an old acquaintance Louise Petion was brought to Ste Pelagie, Manon was saddened, of course, but also relieved: she now had some company.

Unfortunately their friendship was tinged with tragedy. In September 1793, when she heard of the arrest of her daughter, Louise Catherine Angelique Ricard, veuve Lefevre, came to Paris to petition for her release. She was in turns arrested, and take to the Conciergerie. Almost immediately she was tried and condemned to the guillotine on the grounds of defending the re-establishment of monarchy. She is reputed to have claimed, when asking for her daughter's release, that Brissot and Petion and the proscribed Girondins were true republicans, and that if the French people wanted a king, they should have one. She was executed on 24 September 1793, at the age of 56, her daughter was still in Ste Pelagie. When Manon visited with her friend, she would have been dealing with the loss of her mother, but also been fearing for her husband. Jerome Petion had escaped with Buzot, Manon's lover (although the relationship was a secret, so Manon could not tell Louise that he was that). Petion and Buzot died together in a suicide pact. Their bodies were discovered in a forest, eaten by wolves. Louise-Anne Lefevre eventually came out of Ste Pelagie and, after the Terror, was granted a widow's pension. Her son, Jerome, lived on and pursued a military career under Napoleon. When Brissot decided that he would set up his republican colony in France, rather than America, he first approached his friends Bosc and Lanthenas. The latter had some money and was enthusiastic about the idea – although he might have preferred the original plan of going to America. Bosc and Lanthenas suggested the include the Rolands in the plan. Their current way of living, between Lyon where Roland worked, and their idyllic country house, le Clos, together with their shared republican dreams made them perfect for the project. Brissot was introduced, and the friends corresponded. It was decided that they would contact a few others and try to put together enough money, in installments, to buy land and set up the colony. Brissot drafted a plan for what he called an agricultural society, or society of friends. The aim of the society would be twofold: to ‘regenerate’ its own members by cultivating the earth, and to regenerate the local community through a ‘rural education’. The first part of the plan would be to buy property, a land vast enough to house twenty families, each in its own simple and luxury free house, and with room to grow. The land should be in the countryside, contain a wooded area, water, be close to a mountain, and served by a large road. The plan says nothing about how the rural life would help ‘regenerate’ the members of the society. Maybe he felt there was no need, and that anyone interested would already believe in the healing powers of the simple, rural life. This was certainly true of Manon, who even before she was married, and while she still lived in Paris, claimed that the Spartans led the best lives, because they lived in the country, simply, without any luxury. She embraced, and sought to reproduce, whenever she could, the life led by Rousseau’s Julie at Etanges, simply, luxury free, industrious, and always with an eye to the needs and education of the men, women and children working the land she lived on. At le Clos, she even participated in the Vendanges when the season came, picking grapes alongside her peasant neighbours, making friends with them and treating them as equals. When the Great Fear happened, and those who had locked their doors against those who did not, she was secure enough in her relationship with the poor of Le Clos not to run away. Another reason why Brissot may not have felt the need to explain what was in it for the colonists lies in the title of the document in which he details his plan: a society of friends. Brissot had ties with the Quakers of England, whose philosophy and way of life he admired, and when he travelled to America, it is the Quakers he sought, both because he regarded them as a model and because of their work against slavery. His brother in law had immigrated to Philadelphia, a Quakers town, so there were possibly ties to the sect from that side of the family too. Another possible clue to Brissot modeling his proposal on Quakers communities is the content of the educational program the colonists were to dispense to the locals – one in which religion was taught but in very simple, rational terms. Members of the society, when they were not labouring the earth, or reading philosophy, would teach peasants ‘the purest morals, the simplest religious beliefs and how to work with their hands.’ Although the colons were to live simply one thing they would not have to compromise about was reading materials. Brissot takes care to specify in his plan that the colony will house a good library held in common. Should we talk about a colony when they were in fact not planning on leaving the country? It seems so – and moreover that what they intended was a colony in the strong sense, i.e. they wanted to colonize the people living around them, teach them to be other than they were, more virtuous, more efficient in their work, and better republicans. But at the same time they had no intention of living among the peasants as equals, or of integrating the peasants more closely into their communities. The community was one of teachers, who would benefit from a more rural lifestyle, but not peasants. Agriculture and philosophy might live side-by-side, but not together. This separation of status between the colonists and the colonized is reflected in Jean-Marie Roland’s letter to Champagneux in early 1792 – by which time all the land had been bought and all had given up on the dream: I was as sure of this as my existence - to create a monument to patriotism and the useful arts, such as does not exist even in Paris [...] we would have made a community such as never existed before in the provinces, which could have become famous and would have rewarded our pains with either reputation or profit. Perhaps this was not Brissot’s intention, but it seems that for Manon’s husband at least, there was a third aim, beyond self-improvement and improvement of the local peasantry: fame and wealth for the founders.

In 1788 Brissot travelled to America in order to investigate the possibility of removing his family there, and also in order to try and make himself known: Brissot did not wish to give up his literary career, and if he were to move to a large unknown country, he would need the support of influential people. In that sense, his trip was not successful – he did not feel he had made enough of an impact to risk moving his name and career to the other side of the ocean. But the dream remained. When he wrote up his travel notes, which were published in 1792, he emphasized what he saw as the parts of American life worth reproducing: the Americans, he thought, lived well because their lives were simple and virtuous, and everything in it arranged according to reason. This was the dream he was after, and with which he infected his friends, the Rolands, Lanthenas, and Bancal. In a sense, it may have seemed safer to stay than to go. Those who moved to America, taking advantage of the dubious Scioto company, selling worthless land in Ohio, tended to be those who had either tried to make a life for themselves in France and failed, or those who had little hope of succeeding where they were. FelicitéBrissot, writing to her brother in Philadelphia, warns him of the possible arrival of several men they know, and of their various moral failings – one is selfish, another stupid, and a third so bad tempered that he has alienated everyone who could help him. She adds, charitably, that they are young and that therefore they may benefit from the move, but worries nonetheless about the effect of these men on the American communities (in particular the one she thinks of as intellectually limited, because he would, she thinks, encourage gossip). For those who care about the future of France, and who think that they are in a position to benefit the nation through their character, ambition, knowledge, then it is best that they stay and attempt to bring the American model to the new Republic, rather than draining it of its most promising elements in order to join those it has already rejected. Towards the end of 1789, land and building that had belonged to the church were put for sale to private buyers, as a way of reducing the national debt. This was an opportunity for Brissot to put his plans for a colony into practice without leaving the country. There were several reasons why that may have seemed like a good plan to him. First, his trip to America had not been the personal success he had hoped it would be, so that if he moved there, he would not be known as a writer, and could not count on the help he would surely need to establish himself in that profession. Secondly, France was now a desirable place to be for the reason America was: it was on its way to becoming a Republic, a land of freedom. Brissot first approached his friends Bosc and Lanthenas. The latter had some money and was enthusiastic about the idea – although he might have preferred the original plan of going to America. Bosc and Lanthenas suggested he include the Rolands in the plan. Manon Roland became the prime mover behind the plan, which, unfortunately, was never realized.

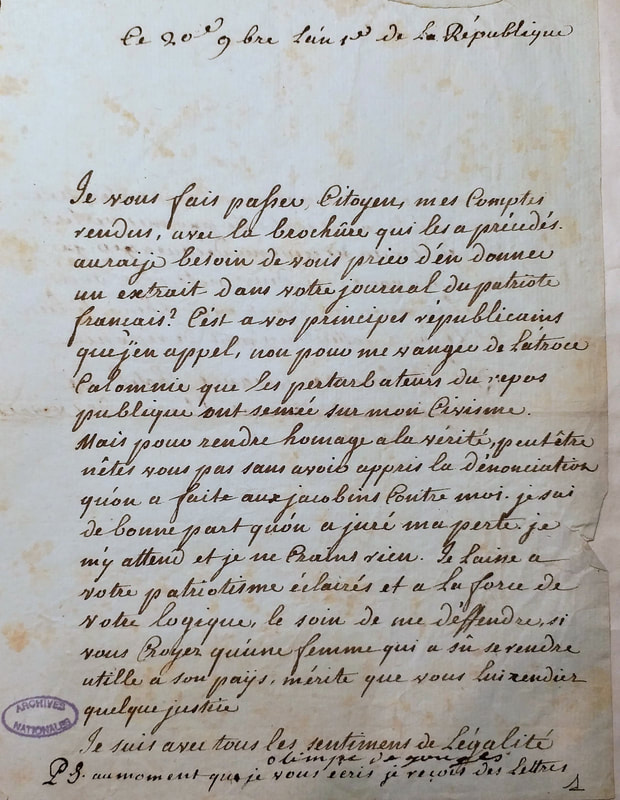

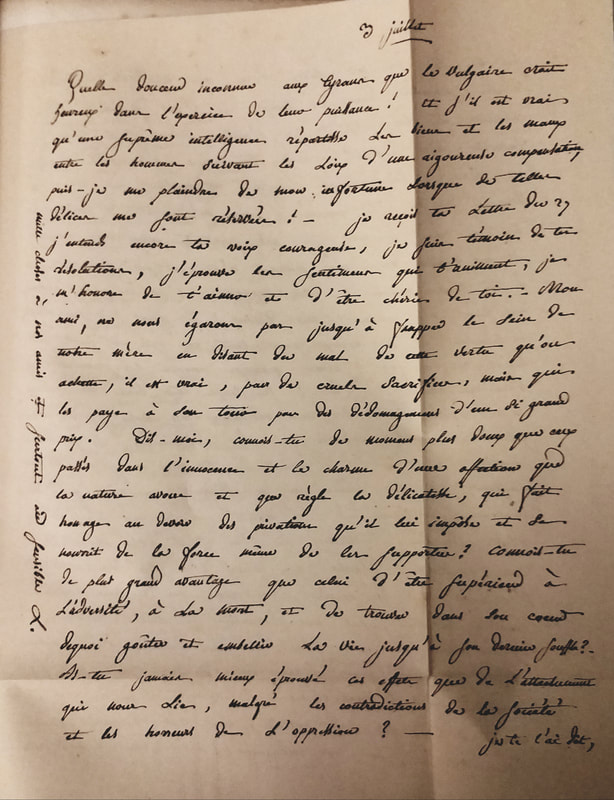

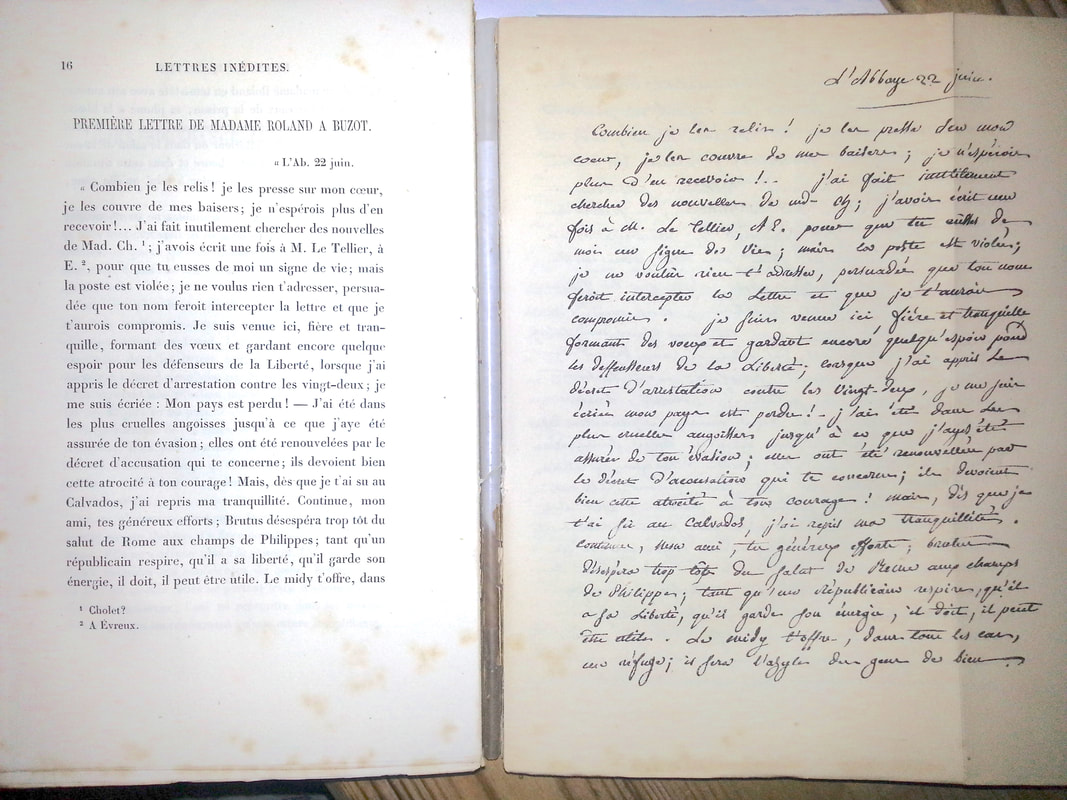

On 20thNovember 1792, Olympe de Gouges wrote to Jacques Pierre Brissot, editor of Le Patriote Francais, sending him a set of documents and asking that he should extract them in his paper. She had been denounced at the Jacobins club and feared for her safety. In the PS, she says that she has also received threatening letters and would like to set up a meeting with Brissot to discuss her situation. Gouges had in fact been denounced at the Jacobins by Leonard Bourdon, for having written against the Jacobins's actions leading to the massacres of 10 August and 2 September 1792. The Jacobins, she claimed, especially Marat and Robespierre, were entirely responsible for inciting popular violence. Interestingly, Manon Roland had blamed Danton for the same thing. But from inside the Government, Manon knew, or suspected, that it was Danton who'd ordered the signal to start the massacre, while Olympe, as a public writer and philosopher, knew that it was the speeches and writings of Marat and Robespierre that had prepared the people to react to that signal. The two documents that Olympe sent Brissot can be found on Clarissa Palmer's excellent site : Court correspondence. A principled report and my last words to my dear friends, by Olympe Degouges [sic], to the National Convention and to the People. On a denunciation made to the Jacobins, against her patriotism, by Monsieur Bourdon Prognostic of Maximilien Robespierre, by an Amphibious Animal published 5 November 1792, in which she attacks Robespierre and Marat for inciting the people to violence on August 10 and September 2. Below is a translation of the letter to Brissot and a photograph of the actual letter taken at the Archives Nationale on 5 June 2019 (446AP/7-18) Note that the letter and the signature are in different hands, as Gouges was using a secretary. Note also that she signs herself 'Olimpe', not 'Olympe'. 20 November, year 1 of the Republic The text below is extracted from Manon Roland’s second letter to her lover Buzot, on 3 July 1793, from the prison of Sainte Pélagie. Do you know a greater advantage than that of being superior to adversity, to death, et to find in one’s heart the means to enjoy and embellish life until one’s last breath? – Have you ever felt these effects from the attachment that ties us together, in spite of all the contradictions of society, and the horrors of oppression? – I told you so: this is why I enjoy my captivity. – I am proud to be persecuted in those times where good character and honesty is proscribed, and even without you, I would have born it with dignity; but with you, it becomes sweet, and dear. The villains think to hurt me by putting me in irons… Insane! What do I care whether I live here or there? Don’t I go everywhere with my heart, and isn’t my constriction me in a cell meant that I am his entirely? […] The rest of the letter casts some light on how she dealt with the fact that she was still married and that her husband, Jean-Marie Roland, was broken-hearted by her emotional desertion. She describes her state of mind when she was arrested: I won’t say I went out of my way to meet them (the men who came to arrest her), but it is very true that I did not run from them. I did not stop to think whether their fury would extend to me, but I thought that if it did, it would give me an occasion to serve X (Roland) through my statements, my constancy and firmness. I delighted in finding a way of being useful to him while at the same time being yours more completely. I would like to sacrifice my life to him in order to earn the right to breathe my last breath for you alone. Except for the terrible unrest when I learnt of the decree against the proscribed, I have never enjoyed such great calm than in this strange situation, and more completely once I learned that nearly all were safe, and once I saw that you were working in freedom to liberty at preserving that of your country. During her trial, and throughout her Memoirs, Manon Roland presented herself as a model wife to her husband. But reading through her recollections of the early days of hers and J.-M. Roland’s courtship, one is underwhelmed. Their courtship was long, their engagement business like – he was always hesitant and there is very little passion showing in Manon’s accounts. It was not a marriage of convenience: Jean-Marie Roland saw his wife as an equal in all respects, he did not attempt to dominate or curtail her, and they were partners in all their projects (except for the Memoirs which she wrote while she was in prison and he in hiding). There was a strong friendship between the two but perhaps not much more. Towards the end of her life, however, Manon did fall in love with a young Girondin (he was six years younger than her, while her husband was twenty years her senior), François Buzot. François was also married, and neither he nor Manon had any intention of breaking down their marriage. Nonetheless, Manon told Jean-Marie that she no longer loved him, and that she loved François. This is perhaps why, in the weeks before her arrest, she had planned to leave Paris. She needed some space to think. Manon's correspondence with Buzot was hidden from the public when the letters were first published, so that the image of her as a virtuous wife remained. But the truth came out in the 19thcentury: after all, all interested parties were dead. Below is a letter Manon wrote to Buzot shortly after she was imprisoned, and after the decree for the arrest of the Girondins had been issued. She had heard that Buzot, together with Jérome Pétion (whose wife was Manon 's neighbour at Sainte Pélagie, had managed to escape and that they were in the South-West of France, near Bordeaux. This is a love letter: she tells him how she covers his letters to her with kisses. But it is also a political letter: one that shows both hope and despair. She tells him that when she heard of the arrest of twenty-two Girondins, she thought France was lost. But then, she asks him to stay alive, because a republican ‘while he breathes, while he has his freedom, can and must be useful’. A few weeks after Manon’s death at the Guillotine, Buzot and Petion shot themselves in the woods of Saint Emilion. Their bodies were discovered later, eaten by wolves. In September 1787, Manon Roland was staying at Le Clos, the Roland family home in the countryside. She and her husband were about to take possession of the house, and she was beginning to renovate it, while Roland was working nearby in Lyon. Eudora, their daughter, was six years old. It’s very cold here, but our rooms are comfortable even without a fire, and one could easily spend the winter here. All that is missing are chairs, which will come on Friday, weather permitting, and the top of the book case, which would not fit on the first cartload. Our child is quite well behaved with me. I have established a schedule, and I think this is an excellent method. We wake up together at six: we get dressed, read catechism and do some needle work, all this together until eight. Then breakfast together, great happiness and play till half past nine. Then we go back upstairs and I write, while the child sews or knits till half-past eleven. Then play for her, but indoors, till twelve. At twelve, she chooses a book to read, then music lesson. Lunch at one. Play until three. Upstairs again then work or reading till five (keeping the readings short). A collation at five, then play till six, or later if we go out; otherwise we go in and she has another music lesson. She dines and goes to bed between seven and eight. I dine after eight and go to bed an hour later. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed