|

When Manon Roland was at the prison of Sainte Pelagie, she found at first the company a bit too loud for her tastes: the prison was full of prostitutes and thieves whose ribald jokes she could hear through the thin walls of her cell. So when an old acquaintance Louise Petion was brought to Ste Pelagie, Manon was saddened, of course, but also relieved: she now had some company.

Unfortunately their friendship was tinged with tragedy. In September 1793, when she heard of the arrest of her daughter, Louise Catherine Angelique Ricard, veuve Lefevre, came to Paris to petition for her release. She was in turns arrested, and take to the Conciergerie. Almost immediately she was tried and condemned to the guillotine on the grounds of defending the re-establishment of monarchy. She is reputed to have claimed, when asking for her daughter's release, that Brissot and Petion and the proscribed Girondins were true republicans, and that if the French people wanted a king, they should have one. She was executed on 24 September 1793, at the age of 56, her daughter was still in Ste Pelagie. When Manon visited with her friend, she would have been dealing with the loss of her mother, but also been fearing for her husband. Jerome Petion had escaped with Buzot, Manon's lover (although the relationship was a secret, so Manon could not tell Louise that he was that). Petion and Buzot died together in a suicide pact. Their bodies were discovered in a forest, eaten by wolves. Louise-Anne Lefevre eventually came out of Ste Pelagie and, after the Terror, was granted a widow's pension. Her son, Jerome, lived on and pursued a military career under Napoleon.

1 Comment

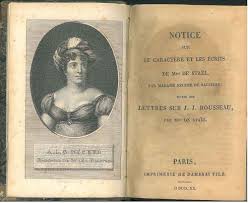

I was alerted by Eveline Groot, who gave a great talk this week at the Braga Colloquium on Women and the Canon, to yet another slight in the history of philosophy against a woman. This time, it's against Germaine de Stael, a writer who saw her share of slights in her life time, including some from Manon Roland and Sophie de Grouchy. But what Eveline Groot found is a 20th century historian of philosophy (or philology), who chooses to minimize the impact and import of Stael's philosophical commentary on Rousseau. Writing in 1915 in Modern Philology (13:7), G.A. Underwood claims that in her reading of Rousseau, Madame de Stael saw only the sentimentalist of the New Heloise, and not the rationalist of the On Social Contract, and that her Notice sur le Caractere et les Ecrits de J.J. Rousseau demonstrate 'little beyond an enthusiasm for Rousseau's ideas' (adding that the enthusiasm itself was significant'. Underwood concludes the introduction to his paper on Stael's interpretation of Rousseau by announcing that: 'The thesis will be that Rousseau leads Madame de Stael to become absorbed in her feelings'. The conclusion of the paper reads as follows: Such is the somewhat undeveloped Rousseauism of Madame de Stael when she began writing. It is an emphasis on temperamental inclination rather than a ripened criticism. A continuation of this study would show how in her mature and original work Madame de Stael gradually thought out to definite literary and philosophical tenets those ideas of Rousseau to which she was so strongly attracted. So one may well wonder why Underwood decided to write the article showing that in her early work, Stael was not a proper philosopher, but yet another female with inflamed emotions, rather than study the philosophical tenets he agrees she later came up with.

We can add G.A. Underwood to the list of scholars for whom, when it comes to the study of women philosophers, the important work to be done is to show how uninteresting and un-philosophical their work was. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed