|

Looking for mentions of Sophie de Grouchy in the 18th century press, I came up against an extremely unpleasant text which would find a home today on the worst alt-right threads. These were unpleasant to translate, and I expect they'll be unpleasant to read - unless you are accustomed to aforementioned threads - so brace yourselves. The text comes from a royalist journal by a M. Suleau, who, having praised aristocratic ladies for their anti-revolutionary attitude goes to lists exceptions: There are of course, exceptions amongst the old, the ugly, the infirm, whatever class they belong to. I have carefully verified that of all the women who harnessed themselves to the cart (or more correctly, the tipcart) of the Revolution, there is not a single one that does not belong to this disgusting category. Francois-Louis Suleau is described in the French Wikipedia article dedicated to him as a passionate defender of monarchy, a provocateur, one who would not accept compromise and bravely attempted to convince first Mirabeau, then Danton and Robespierre to preserve the monarchy.

Readers will no doubt be sad to hear that this noble individual came to a violent and inglorious end at the age of 34, massacred by the crowds in front of the Tuileries on August 10 because they'd mistaken him for another - more influential - counter revolutionary journalist.

0 Comments

Although she became a political thinker at a very early age – eight, if we believe her memoirs, being the age she discovered Plutarch and decided she too was a republican – Manon did not become interested in politics until the Revolution. That is, she was interested in political theory, but felt that these were so distant from the shenanigans at Versailles that her interest had to remain political. In the early 1780s, Manon Roland had lost all illusions that the world would ever be ruled in a just manner. In 1783, she wrote to her friend Champagneux: Virtue, liberty, are only to be found in the hearts of a small number of decent people; to hell with the others and all the thrones in the world! But from the very start of the revolution, when she was recovering from pneumonia and writing powerful letters to her friends in Paris, advising and admonishing as to what had to be done, Manon became fully involved. She wrote letters and newspapers articles, and helped Jean-Marie find a position for himself that would allow them to participate more fully. As soon as it became possible the Rolands moved to Paris. In June 1791, she wrote to her friend Bancal explaining her transformation: While peace lasted, I kept myself to the tranquil role and the kind of influence that seem to me proper for my sex. But when the King’s departure declared war, it struck me that we must all devote ourselves without reserve; I went and joined the Fraternal Societies, persuaded that zeal and right thinking can sometimes be very useful in times of crisis. I cannot keep to my home and am visiting all my acquaintances in order to excite us for the greatest actions. In 1777, the Académie of Besançon proposed an essay competition with the following question: How can educating women contribute to the improvement of men? Such competitions were common at the time, a way both for the provincial academies to make themselves known throughout the country, and for fledgling writers to get published. Competitions were especially rife during the decades preceeding the Revolution, with 357 between 1770 and 1779, that is, more than 35 per year. As well as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose career as a writer took off when he won the Academy of Dijon competition with his Discourse on the Arts and Sciences in 1749, many famous names of that time entered and won academic competitions, such as Jean-Francois Marmontel, novelist and friend of Olympe, Jacques Pierre Brissot, Abbe Gregoire and Jean-Paul Marat to edit. Manon’s first mention of her academic project to her friend Sophie Cannet is very brief, and almost blustery – look at all the crazy things I’m trying to do, she seems to say – none of them will come to anything: 14 January 1777 In April she sent it the Academy, and in June, still waiting for an answer, she told her friend about it: 21 June 1777 It turned out nobody won. Bernardin de Saint Pierre, Rousseau’s disciple, and author of the novel Paul and Virginie, got an honorary mention.

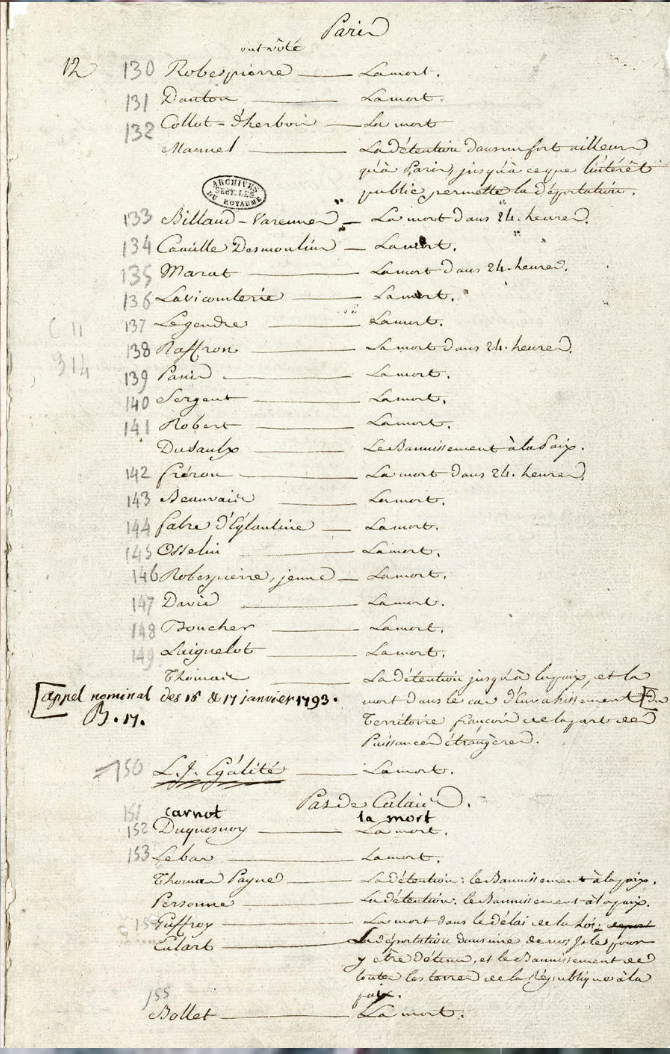

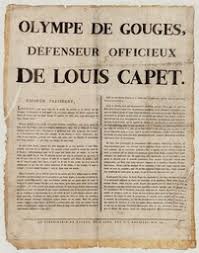

On 15 January 1793, Louis Capet, previously King of France, is found guilty by an overwhelming majority of the 749 deputies. Two days later, the deputies are asked to vote for a penalty. 346 vote for the death penalty. Others, including Thomas Paine, who had been offered honorary French citizenship, vote for exile, or for imprisonement. . One citizen, who had not voted, argued against the death penalty. Olympe de Gouges started by offering herself as Louis’s unofficial advocate on 16 December, arguing at first that while as a King, he had done harm to the people of France by his very existence, once Royalty had been abolished, he was no longer guilty. As king, I believe Louis to be in the wrong, but take away this proscribed title and he ceases to be guilty, in the eyes of the republic. This proposal, written as a letter to the Convention, was then printed as a placard and distributed throughout Paris. The Convention disregarded the letter. Sèze was made Louis’ advocate, and the argument that Gouges put forward was not taken into consideraton. Louis Capet, stripped of his title, was still tried for high treason, i.e. for actions he had performed while he was still King of France. Olympe did not stop at this. On 18 January, after the King had been found guilty, but before his death had been voted, she put up another placard addressed to the Convention and to the people of Paris, entitled “Decree of Death against Louis Capet, presented by Olympe de Gouges.” In this piece she also attempted to dispel the mistaken impression that she was in fact a royalist. Louis dead will still enslave the Universe. Louis alive will break the chains of the Universe by smashing the sceptres of his equals. If they resist? Well! Let a noble despair immortalize us. It has been said, with reason, that our situation is neither like that of the English nor the Romans. I have a great example to offer posterity; here it is: Louis' son is innocent, but he could be a pretender to the crown and I would like to deny him all pretension. Therefore I would like Louis, his wife, his children and all his family to be chained in a carriage and driven into the heart of our armies, between the enemy fire and our own artillery. (http://www.olympedegouges.eu/decree_of_death.php) Here Gouges is appealing to a well-known fact about the workings of royalism: a King cannot die. The holder of the title may die, but the title passes automatically to the next contender, without, even, the necessity of sacrament. The immortality of the king was such an important precept that a Chancelier, when a monarch died, could not wear mourning. Bossuet captured the phenomenon thus in his Mirror for Kings: Letting Louis live, she would go on to argue in her final published piece, 'Les trois urnes'. would have made it clear that he was no longer a threat to the republic - as no one individual is. To execute him is both to betray a certain lack of confidence in whether the people have truly succeeded in aboloshing the monarchy, and perpetuate that doubt, as after Louis's death, his title is transferred to his descendent.

|

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed