|

In the 18thcentury, a total of 6 548 195 Africans children and adults embarked on vessels to be sold as slaves, and a total of 5 654 009 disembarked on the other side. 1 141 059 were destined to be sold to French planters (960 603 made it that far), 2 570 366 for England (and 2 169 659 made it alive) 2 235 417 for Brazil and Portugal (with 1011 417 arriving alive) and 189 342 to the United States. [1] (Note that the United States only existed for the last 21 years of the 18thcentury, so most of the slaves brought to the Americas were in that century were ‘owned’ by Europeans). [1]Numbers obtained from the Transatlantic Slave Trade Database and ‘World Population Growth’ by Max Roser and Estaban Ortiz-Ospina, 2017. Current estimates of slavery in the 21stcentury range from 21 to 40 millions, with the majority of cases being forced to engage in sex labor. These numbers, however, are subject to controversy. The often quoted 27 million was a speculative number arrived at in the 1990s by Kevin Bales. The NGO responsible for the higher figure is Walk Free, who produces an annual Global Slavery Index This number, however, is indicative of ‘modern slavery’ which includes a number of different categories such as bonded labour, forced marriage, child labour, and sex trafficking. These ways of treating human beings, while highly objectionable, do not, however, always constitute slavery. And even if were tempted to redefine slavery, or ‘modern slavery’ to include all of these categories no matter what the circumstances, the numbers would still be unrepresentative when compared to 18thcentury numbers, as forced marriage, child labour, sex trafficking and prison labour were mostly deemed acceptable. (Thanks to Laura Brace for alerting me to the controversy about modern slavery data).

Another way of looking at this is through proportions. There are now 7.5 billion people in the world but less than a billion (0.8) in the 18th century. This means that at worst, the percentage of slaves in this century is just under 1% of the population (which is a huge amount) and at best less than 0.3% (which is still a huge amount). Given the fact that we are comparing ourselves to a century where child labour and forced marriage were very common, it makes more sense to take the lower figure (which may be more accurate). According to the reliable numbers we get from the Transatlantic Slave Trade database, in the 18thcentury, the slave population amounted to 0.8% of the population. But this percentage only takes into account the number of slaves transported in the 18thcentury, and not the number of slaves in a country at any one time. For a more accurate comparison, we would need to know how many were enslaved, taking into account not only survival rates from the transportation but also children born in slavery. So the proportion of slaves to free people was a little higher in the 18thcentury than it is now.

0 Comments

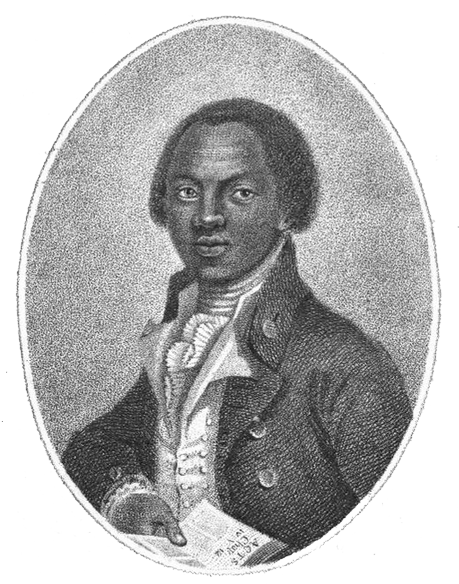

Many republican philosophers of the French Revolution, including Olympe de Gouges, Manon Roland and Sophie de Grouchy, understood the liberty they fought for as the absence of domination, rather than, as later liberal thinkers would, the absence of interference. The two are distinct in several ways, but one way in which they are is this: someone who is dominated, under the power of another, whether a slave, or a wife, or even a child, may well be free from interference at the same time = - but this does not make them free. This point is clearly illustrated by the narrative of Olaudah Equiano, 18thcentury African writer and abolitionist, who toured England in the 1780s, speaking, amongst other places, in Newington Green, Mary Wollstonecraft’s home at the time. In 1789, Equiano published his Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the Africanand Wollstonecraft reviewed it for the Analytical Review(she was on the whole enthusiastic but felt the discussion of his religious beliefs at the end was rather boring). Equiano had been sold as a child to an English navy officer, and when they were not at sea, he lived in his master’s London house, where he was taught to read and write, and even baptized by the lieutenant’s daughter. Because he was treated kindly, and accepted as one of the family by his master’s daughter, Equiano developed a sense of security, thinking of himself as something other than a slave: For though my master had not promised it to me, yet, besides the assurances I had received that he had no right to detain me, he always treated me with the greatest kindness, and reposed in me an unbounded confidence. And yet, one day, after months of fighting alongside each other, the lieutenant sold him. Equiano was told to board a barge from where he would join a ship sailing to Montserrat in the Caribbean: I made an offer to go for my books and chest of clothes, but he swore I should not move out of his sight; and if I did he would cut my throat, at the same time taking his hanger. I began, however, to collect myself; and, plucking up courage, I told him I was free, and he could not by law serve me so. But this only enraged him the more. The ship captain introduced himself as his new master, leaving no doubt, this time, as to what the relationship would be: 'Then,' said he 'you are now my slave.' I told him my master could not sell me to him, nor to any one else. 'Why,' said he,'did not your master buy you?' This is a clear example of someone who thought they were free, because they were allowed to educate themselves and work for money (even though Equiano gave his wages to his master, he seemed to have been under the illusion that it was for his upkeep, and he managed to retain enough to buy books). The lieutenant did not interfere with his efforts to better himself; he encouraged him by letting him be educated with and by his daughter. He acted kindly and generously. And yet, at a moment’s notice, with no explanation, he sold him off to a violent man, to an uncertain (but certainly miserable) fate. And even then it took young Olaudah a while to realize that he had not been, at any point, free, that his sense of freedom had been but an illusion, and that all along he had been under the power of his master, depending on his goodwill (or laxity). As soon as that good-will was exhausted, simply because the master needed money, the lack of freedom became painfully apparent.

|

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed