|

Because I'm very jet=lagged from my trip to the APA in Vancouver, this week instead of a post I will share part of a less philosophical project - a series of portraits of women philosophers at work, paired with fictional extracts from their diaries. So here is Sophie de Grouchy, depicted writing her Letters on Sympathy and with a fictional extract from a diary from January 1794. Silk stays, linen shifts, neck ruffles. It’s all in order. Cardot clearly has a way with women’s underwear. He has a way with the customers too - charming, and not intimidating, so that they feel they can ask him for their intimate needs, or that of their mistresses in some cases still - not all class privilege is gone! I must remember to pick up a new shift for my old nanny before I go. And shirt sleeves for my sister, Charlotte. None of us want stays - one good thing about the revolution is that we have loosened our underwear! Also, I could not possibly walk all the way from Auteuil dressed like a lady. I will take off my peasant dress, now I’m here, and put on my work clothes which are waiting for me upstairs, in the studio. I have three commissions to catch up on. Two that pay, and one for free, a portrait of a young girl who is at the Conciergerie, for her mother. I could not bear to charge her for it. I am late though, and I wouldn’t be if it were not for those men who came to arrest me and Cardot last week. I spent days painting their portraits, just so they would leave us alone. Not that they had any grounds to arrest us. I am no longer married to Condorcet, and Cardot is working for me, not for my husband, nor for his brother, my husband’s secretary. I do enjoy the painting - when it’s not for a brute of a police man. I miss the writing. Of course, I help my husband (I still call him that - the divorce is on paper only). Everyday I see him, which is most days except when I think I might be followed, or at the weekend, I spend an hour or so reading what he has written, and discussing it with him. I dare not take it with me - I don’t want it discovered in a search and destroyed. But I know I will have to look after it, eventually, and keep it safe until it can be published and until Condorcet can come out of hiding. I say we work together - and we do - but of lated I feel most of my efforts are directed to helping him feel better. He is not looking after himself, and his spirits are depressed. His landlady, his saintly landlady, is helping of course. And most of the time, he dares not refuse the food she offers him. But there is only so much she can do. Only so much I can do too. I keep telling him that soon it will be over, and that he'll come back home to me and our daughter, but it seems he does not have the patience to wait any more.

0 Comments

The Code Napoleon, first modern civil code which spelt out the laws regarding marriage, and inheritance in its first part and, although it has been revised several times since its publication in 1804, is still very influential in French civil life.

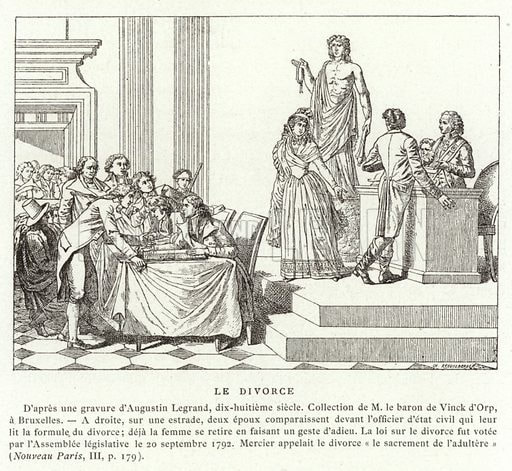

One of the principal aims of the new code was to free the family from the shackles of the church and prejudice. Marriage is described as a contract whereby men and women acquire certain rights and duties pertaining to each other and their children. It is possible to see this project as in part defending women’s positions, by making it a public, rather than a private matter. In particular the reforms of the divorce law, while making it harder for a marriage to be dissolved by mutual agreement, also made it nearly impossible for a man to divorce his wife once she was no longer young. But the code is nonetheless very asymmetrical – husbands owe wives protection, but wives owe husbands obedience (article 214) and a wife is obliged to live where her husband decides (215) and cannot plead in her own name unless she has her husband’s permission (216). A woman, but not a man, must wait ten months to remarry after the dissolution of a first marriage (228). While both husband and wife can ask for divorce on grounds of adultery, a woman can only ask for it in case where her husband had moved his mistress into the common home (230). In cases of divorce, the father is given the management of the children (287) except in special circumstances decided by the court. And although many articles refer to both paternal and maternal authority over minor children, there is a whole section dedicated to Paternal Power. One of the main writers of the Code, and the one responsible for the section of family law (I Of Persons) was Jean Etienne Marie Portalis (1746-1807). Portalis, a lawyer from the South East of France, was chosen by Napoleon to help carry out the project begun by Cambaceres under the Directoire of codifying civil law. Portalis was very concerned that the mew Revolutionary laws should not overturn the laws of nature and morality, and this was particularly clear in his treatment of the family part of the civil code. In his Preambule he talks of marriage as a ‘natural order’ that had been in the past sanctified by religion and needed to be recognized by the law. Part of this natural order was the need for one party in the ‘marriage contract’ to be in charge, and that had to be the husband, who was naturally superior to his wife and naturally destined, through his experience and wisdom to have authority over their children. In discussions of the code at the Council of State, Portalis worried about any addition to the marriage law that would have the effect of placing ‘the wife above the husband, or put the power over children into the wife’s hands instead of the husband.’ He concluded that ‘any stipulation against the authority of a husband on the person of his wife or children must be forbidden’, that public right must be confined by public order and morality, and that the main object of family law was to confirm the husband’s rightful place as the head of the conjugal society. After Condorcet's death, Sophie kept up her salon, first in Auteuil, in the house next to Madame Helvetius, and later in Meulan, close to the castle of Villette where she had grown up. The house she bought had been built in 1642 by Anne of Austria for the religious order of the Annonciades. It was several storeys high and set in the countryside, between the town and the castle of Villette. The nuns who’d occupied it had been evicted 5 years previously and the house had already exchanged hands a few times. Sophie called it the ‘Maisonnette’ or little house, despite its generous size. One of the rooms was a large salon where she could host her philosophical circle, and there were several bedrooms upstairs for guests. (for more on the purchase and the set up of the house, see Madeleine Arnold-Tetard's excellent blog.) Sophie’s salon was a place where she could discuss her ongoing work with close friends such as Cabanis, it was a meeting place for the Ideologues, and it also played a role in facilitating other’s literary careers. Karl Benedikt Hase, a Byzantine expert who came to play an important role in the literary world of 19thCentury Paris, was first introduced to this world by a chance meeting with Sophie de Grouchy. Having walked on foot to Paris from Weimar, and arriving a poor student, he was recommended to various people for his knowledge of Ancient Greek, and brought to Meulan by Sophie’s lover, Fauriel: I already talked about Madame Concordet in one of my letters. I got to know her by chance; she wanted to learn German and a certain Fauriel, private secretary to the police minister, with whom I sometimes spend the evenings, sent me to her. It was the 28th Frimaire; look up the date and underline it, it is one of the most important in the life of your friend. I’ll admit it – the clear mind of this wonderful woman, her joy in the all-pervasive progress of humanity to a marvellous goal, her knowledge of the great moments of the revolution, in which she herself played a not insignificant role (on the day before the 10th August, when Concordet, her husband, played host to 400 Marseillese, she was the queen of the party), perhaps also her friendly attitude towards me – for my significant progress in French pronunciation, which has astonished everyone, was thanks to my reading French tragedies aloud to her – could not fail to have an effect on me. In the Ancient Regime, a French marriage could only be annulled through a special dispensation from the pope. In 1792, divorce became legal. It was possible to divorce in two ways. First, a couple could decide they simply no longer wanted to be married. In this case, they simply had to wait six months after submitting a demand for divorce, and the divorce would be accepted after that period. One spouse could also ask for divorce for cause of cruelty, desertion, infidelity. Until the Napoleonic period, divorce was quite easy to obtain. Napoleon made it harder, and by 1816 it was no longer legal. The first divorce laws were drafted after 10 August 1792, when the republic was proclaimed. This was in spite of the Constitutional committee having decided that the Constitution of 1791 would remain, only with amendments pertaining to the King’s role (which would be deleted). But divorce was very much on everybody’s minds, and had been since 1789 when the freeing of France from despotism was likened to the freeing of a woman from marriage to a tyrannical husband. One defender of the Revolution wrote that France, ‘a nation for so long oppressed by despotism and its laws, all of a sudden becoming mistress of its own destiny, aspires for liberty…” (Comte D’Antraigue, quoted in Suzanne DesanThe Family on Trial in Revolutionary France. Berkeley: University of California Press. 2004, 15). So from the beginning the French saw strong connections between the state and the family, the public and the private. As soon as the revolution started, the public debate on marriage laws, which had already existed but been contained by the laws and the all powerful clergy, amplified. Women’s clubs throughout France discussed divorce, and the Cercle Social in Paris, and its women only offshoot, Le Club des Amis de la Verité, led by Etta Palm d’Aelders, spearheading the discussion.

In 1792, the divorce law was pronounced. Between January 1793 and June 1795, the assembly received large quantities of petitions – two thirds of which were written by women (sometimes badly written, depending on their social class and level of education) for divorces. 6000 divorces were pronounced during the course of these two and a half years. Women who petitioned typically expressed their wishes in terms of oppression and tyranny, and all those who petitioned were determined, one way of another to free themselves from the marriage chains. Republican freedom truly took its place in the family. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed