|

When Brissot decided that he would set up his republican colony in France, rather than America, he first approached his friends Bosc and Lanthenas. The latter had some money and was enthusiastic about the idea – although he might have preferred the original plan of going to America. Bosc and Lanthenas suggested the include the Rolands in the plan. Their current way of living, between Lyon where Roland worked, and their idyllic country house, le Clos, together with their shared republican dreams made them perfect for the project. Brissot was introduced, and the friends corresponded. It was decided that they would contact a few others and try to put together enough money, in installments, to buy land and set up the colony. Brissot drafted a plan for what he called an agricultural society, or society of friends. The aim of the society would be twofold: to ‘regenerate’ its own members by cultivating the earth, and to regenerate the local community through a ‘rural education’. The first part of the plan would be to buy property, a land vast enough to house twenty families, each in its own simple and luxury free house, and with room to grow. The land should be in the countryside, contain a wooded area, water, be close to a mountain, and served by a large road. The plan says nothing about how the rural life would help ‘regenerate’ the members of the society. Maybe he felt there was no need, and that anyone interested would already believe in the healing powers of the simple, rural life. This was certainly true of Manon, who even before she was married, and while she still lived in Paris, claimed that the Spartans led the best lives, because they lived in the country, simply, without any luxury. She embraced, and sought to reproduce, whenever she could, the life led by Rousseau’s Julie at Etanges, simply, luxury free, industrious, and always with an eye to the needs and education of the men, women and children working the land she lived on. At le Clos, she even participated in the Vendanges when the season came, picking grapes alongside her peasant neighbours, making friends with them and treating them as equals. When the Great Fear happened, and those who had locked their doors against those who did not, she was secure enough in her relationship with the poor of Le Clos not to run away. Another reason why Brissot may not have felt the need to explain what was in it for the colonists lies in the title of the document in which he details his plan: a society of friends. Brissot had ties with the Quakers of England, whose philosophy and way of life he admired, and when he travelled to America, it is the Quakers he sought, both because he regarded them as a model and because of their work against slavery. His brother in law had immigrated to Philadelphia, a Quakers town, so there were possibly ties to the sect from that side of the family too. Another possible clue to Brissot modeling his proposal on Quakers communities is the content of the educational program the colonists were to dispense to the locals – one in which religion was taught but in very simple, rational terms. Members of the society, when they were not labouring the earth, or reading philosophy, would teach peasants ‘the purest morals, the simplest religious beliefs and how to work with their hands.’ Although the colons were to live simply one thing they would not have to compromise about was reading materials. Brissot takes care to specify in his plan that the colony will house a good library held in common. Should we talk about a colony when they were in fact not planning on leaving the country? It seems so – and moreover that what they intended was a colony in the strong sense, i.e. they wanted to colonize the people living around them, teach them to be other than they were, more virtuous, more efficient in their work, and better republicans. But at the same time they had no intention of living among the peasants as equals, or of integrating the peasants more closely into their communities. The community was one of teachers, who would benefit from a more rural lifestyle, but not peasants. Agriculture and philosophy might live side-by-side, but not together. This separation of status between the colonists and the colonized is reflected in Jean-Marie Roland’s letter to Champagneux in early 1792 – by which time all the land had been bought and all had given up on the dream: I was as sure of this as my existence - to create a monument to patriotism and the useful arts, such as does not exist even in Paris [...] we would have made a community such as never existed before in the provinces, which could have become famous and would have rewarded our pains with either reputation or profit. Perhaps this was not Brissot’s intention, but it seems that for Manon’s husband at least, there was a third aim, beyond self-improvement and improvement of the local peasantry: fame and wealth for the founders.

0 Comments

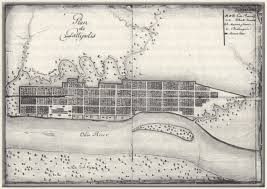

In 1788 Brissot travelled to America in order to investigate the possibility of removing his family there, and also in order to try and make himself known: Brissot did not wish to give up his literary career, and if he were to move to a large unknown country, he would need the support of influential people. In that sense, his trip was not successful – he did not feel he had made enough of an impact to risk moving his name and career to the other side of the ocean. But the dream remained. When he wrote up his travel notes, which were published in 1792, he emphasized what he saw as the parts of American life worth reproducing: the Americans, he thought, lived well because their lives were simple and virtuous, and everything in it arranged according to reason. This was the dream he was after, and with which he infected his friends, the Rolands, Lanthenas, and Bancal. In a sense, it may have seemed safer to stay than to go. Those who moved to America, taking advantage of the dubious Scioto company, selling worthless land in Ohio, tended to be those who had either tried to make a life for themselves in France and failed, or those who had little hope of succeeding where they were. FelicitéBrissot, writing to her brother in Philadelphia, warns him of the possible arrival of several men they know, and of their various moral failings – one is selfish, another stupid, and a third so bad tempered that he has alienated everyone who could help him. She adds, charitably, that they are young and that therefore they may benefit from the move, but worries nonetheless about the effect of these men on the American communities (in particular the one she thinks of as intellectually limited, because he would, she thinks, encourage gossip). For those who care about the future of France, and who think that they are in a position to benefit the nation through their character, ambition, knowledge, then it is best that they stay and attempt to bring the American model to the new Republic, rather than draining it of its most promising elements in order to join those it has already rejected. Towards the end of 1789, land and building that had belonged to the church were put for sale to private buyers, as a way of reducing the national debt. This was an opportunity for Brissot to put his plans for a colony into practice without leaving the country. There were several reasons why that may have seemed like a good plan to him. First, his trip to America had not been the personal success he had hoped it would be, so that if he moved there, he would not be known as a writer, and could not count on the help he would surely need to establish himself in that profession. Secondly, France was now a desirable place to be for the reason America was: it was on its way to becoming a Republic, a land of freedom. Brissot first approached his friends Bosc and Lanthenas. The latter had some money and was enthusiastic about the idea – although he might have preferred the original plan of going to America. Bosc and Lanthenas suggested he include the Rolands in the plan. Manon Roland became the prime mover behind the plan, which, unfortunately, was never realized.

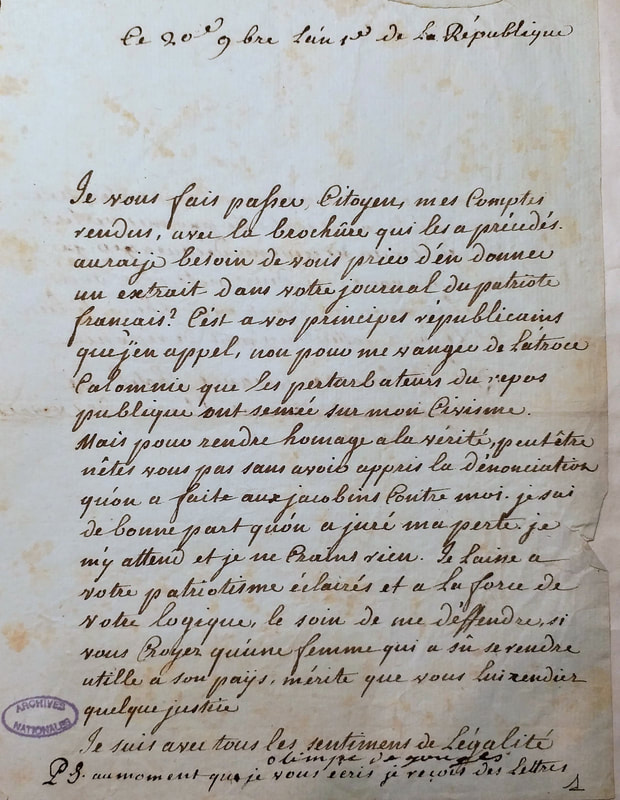

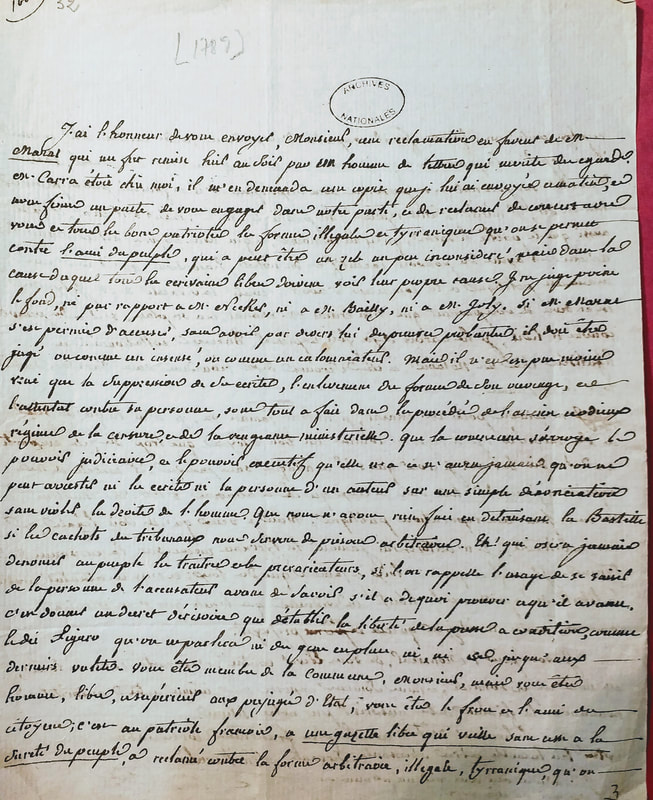

On 20thNovember 1792, Olympe de Gouges wrote to Jacques Pierre Brissot, editor of Le Patriote Francais, sending him a set of documents and asking that he should extract them in his paper. She had been denounced at the Jacobins club and feared for her safety. In the PS, she says that she has also received threatening letters and would like to set up a meeting with Brissot to discuss her situation. Gouges had in fact been denounced at the Jacobins by Leonard Bourdon, for having written against the Jacobins's actions leading to the massacres of 10 August and 2 September 1792. The Jacobins, she claimed, especially Marat and Robespierre, were entirely responsible for inciting popular violence. Interestingly, Manon Roland had blamed Danton for the same thing. But from inside the Government, Manon knew, or suspected, that it was Danton who'd ordered the signal to start the massacre, while Olympe, as a public writer and philosopher, knew that it was the speeches and writings of Marat and Robespierre that had prepared the people to react to that signal. The two documents that Olympe sent Brissot can be found on Clarissa Palmer's excellent site : Court correspondence. A principled report and my last words to my dear friends, by Olympe Degouges [sic], to the National Convention and to the People. On a denunciation made to the Jacobins, against her patriotism, by Monsieur Bourdon Prognostic of Maximilien Robespierre, by an Amphibious Animal published 5 November 1792, in which she attacks Robespierre and Marat for inciting the people to violence on August 10 and September 2. Below is a translation of the letter to Brissot and a photograph of the actual letter taken at the Archives Nationale on 5 June 2019 (446AP/7-18) Note that the letter and the signature are in different hands, as Gouges was using a secretary. Note also that she signs herself 'Olimpe', not 'Olympe'. 20 November, year 1 of the Republic In the Archives Nationales, I found a set of letters from Louise Keralio to Jacques Pierre Brissot. The letters are kept in a folded paper, which notes that one of the letters is about Marat. The letter in question is undated, but from the reference to Marat’s denunciation of Necker means that the letter must be have been written towards the end of October 1789. Here is a – translated – extract: It is my honour to send you, Monsieur, a claim on behalf of M. Marat which was handed me yesterday evening by a man of letter who deserve our consideration. M. Carra was at my home, and asked me for a copy that I sent him this morning, and we made a pact to win us over to our side and to [?] with you and all good patriots against the illegal and tyrannical acts that have been allowed against the ‘Ami du Peuple’ whose zeal is perhaps a little inconsiderate, but for in cause all free writers should recognize their own. I do not judge of the content with respect to M.Necker, M.Bailly or M. Joly. If M.Marat allowed himself to make accusations without probable proofs, he must be judged either as a madman or a slanderer. It is nonetheless the case that to suppress his writings, and to attack his person belond entirely to the ancient and odious regime of censorship and ministerial revenge. […] One cannot put a stop to the writings or the person of an author on a simple denunciation without violating the rights of man. We have done nothing by destroying the Bastille if the tribunal’s lock-ups serve as arbitrary prisons. Louise Keralio was then already a friend and correspondent of Brissot – they had advertised each other’s journals, and praised each other’s work and ideas. Keralio had not, however, met Marat, and had only read a few articles by him. She supposes that Marat is a good citizen whose zeal has carried him beyond acceptable limits. But what she cares about is that the French Press should be treated legally, and not tyrannically. She cites Beaumarchais’ Figaro, jesting that the press should be free, provided it does not mention important people, religion, or anything contentious. She begs Brissot to use his influence to interfere on behalf of Marat, l’Ami du Peuple, and make sure that he is asked to present his proofs so that if he has them, it is known that he did not slander Necker, Bailly and Joly, and that if he doesn’t, the reputation of these three will be cleared in the eyes of all.

Marat quickly came to be regarded as a threat by the Girondins – especially after he voiced his opinion that the best way to safeguard the revolution would have been to cut off six hundred heads. He went into exile, came back, was tried, imprisoned for a month, and acquitted before he became one of the leaders of the Terror. In September 1792, he tried to have Brissot arrested. One wonders if Brissot looked back then, on Louise Keralio’s petition three years earlier, that he should stand up for Marat… Marat was murdered in July 1793, by Charlotte Corday, who’d decided that by killing Marat she could put a stop to the Terror and protect the republic. In 1789, Keralio wrote Brissot the following letter: Mademoiselle de Keralio is very satisfied by what [Monsieur Brissot de Warville] said today about the influence of women. It is very much part of Melle de Keralio’s principles that women should not make a great spectacle of themselves. […] A love of publicity is bad for modesty, from the loss of that comes a distaste for domestic work, and from idleness, principles are forgotten and from lack of morals arise all of public disorders. What did Brissot write to Keralio to make her thank him for his ‘little lesson’ and assure him at length that she did not think women should do politics? Vicky Mistacco suggests that we can guess somewhat what he said from his published response to women’s presence in the Assembly where he describes the women who walked to Versailles as 'revolting' and their entering the Assembly to deliver the King as a religious transgression. Brissot’s sexism was particularly insidious because he was a great supporter of individual women, an admirer of their work. He was close to Keralio, but also to Manon Roland, and had been very interested in Olympe de Gouges’ s work, promoting her play on slavery, and invited her to join his Society for the Friends of the Blacks. When such an ally also argues, politely, with restraint, that women should not do politics openly, then it is difficult not to listen. We are often led to wonder why a person who is politically sound, and who is apparently unthreatened by strong and talented women, can turn out to hold sexist views. In most cases, we have no way of knowing. But Brissot, in the Memoirs he wrote in the prison de l’Abbaye (in the cell Manon Roland had just vacated, and where she’d begun her own Memoirs) gives us an insightful account of his own sexism. He describes his attitude to politically engaged women in 1782, when he was visiting Geneva. Because it is such a rare moment of clarity coming from someone who was sexist, I reproduce it entirely: […] politics seemed a heavy and boring science, unsuitable for a pretty woman. To please and to entertain was the great art that women were to learn their entire life. And if the philosophy I professed forced them to take up other studies, it was of the virtues that could render a wife or a mother’s company useful and pleasant for her spouse and children. In a word, a woman given to politics seemed to me a monster, or at least, a new kind of ‘precieuse ridicule’.” So Brissot tells us that his views were absurd – he might have said they were also harmful, dangerous, even. And he attributes them to a weaker commitment to the truth than was needed, but also to his fashionable love for Rousseau – either way, he was carried by the whirlwind of prejudice.

Louise Keralio, historian, novelist, and journalist has been accused of sexism because of her emphasis on domestic virtues and political silence for women. (She has also been accused of misogyny because of an anonymous tract that we have no reason to think she wrote The Crimes of Queens). * Keralio emphasizes that women have a duty assigned them by nature to prefer domestic work to politics, and that this is essential to the well-being of the nation. In a letter to Brissot she wrote: A great love of publicity harms modesty. And from the loss of this great good comes distate for domestic work, and from lack of work, the forgetting of principles, and from loss of morals, all public disorders. But Keralio was definitely also of the opinion, at least in 1789, that France could only gain from letting her help shape the revolution. And she did not wait to be asked, but started a newspaper, Le Mercure National. Before that, she had been working on an anthology project, intending to publish forty volumes of works by French women writers, starting from Heloise. She had to give up after 6 volumes, due to lack of funds. But what she says in the early volumes is significant. Her account of Heloise, in particular, sheds light on her own ambitions. Heloise, she says, was a natural genius, superior in intellect to everyone of her contemporaries, regardless of sex. Yet, there was another account of Heloise from a strong influence on Louise Keralio: Rousseau’s. Rousseau’s heroine, in Julie or the New Heloise, starts off, like the real Heloise as the bright student of a philosopher. But when she discovers her true purpose, domesticity, she gives up all thoughts of feeding her intellect and devotes herself to her children, husband, and the neighbours, becoming the guarantor of virtue and stability at home and in the village. We tend to think that the shackles of domesticity have always held us back, that we are fighting the same gender stereotypes that our foremothers fought, from prehistoric times onwards. That we are fighting stereotypes is true, as it is that we are fighting off male domination. But the stereotypes were not always what they are.

In the 18thcentury, women were not necessarily thought of as ideal mothers, or virtuous wives. This is something that came from Rousseau, who revived the ideals of motherhood (making sure also that it couldn’t reach too great heights). This, as also his claim that mothers should feed their children themselves instead of employing the services of wet-nurses, was felt as liberating by some women. They were given a role in society that they didn’t have before. They were no longer just an extra pair of hands in the family business, or an ornament for the rich. They were the guarantors of virtue in the home and the republic. So it's no great wonder that a woman like Keralio who admired both the historical Heloise for her intellect and Rousseau’s New Heloise, for the advance in women’s place in society she represented at the time, appears somewhat muddled to 21th century feminists! * Thanks to Vicki Mistacco for sharing her research on Louise Keralio, and in particular for pointing me toward the letter to Brissot and the influence of Heloise of Argenteuil. In 1783 Olympe wrote her first play, Zamore et Mirza, ou l’heureux naufrage, and submitted to the Comédie Française. The actors liked it and accepted it. Unfortunately, her later dispute with Beaumarchais over Le Marriage Innatendu de Chérubin, meant that the Comédie just sat on her play and refused to put it on. The contract she had signed with them meant that it could not be played elsewhere in Paris. So Olympe took the play elsewhere, with her own theatrical troup, which included her son, and performed it in private theatres and in the provinces. In 1786, she had the play printed for the fist time. Two years later, she printed it again, with a postface, her “Réflections sur les hommes nègres” in which she explained what the philosophy behind the play was. Why are black people treated like animals, she asked? [I] clearly observed that it was force and prejudice that had condemned them to this horrible slavery, that Nature had no part in it and that the unjust and powerful interest of the Whites was responsible for it all. In 1788, Olympe was already sensing a change for the better in politics, and felt it her duties to show the world that if they wanted to redress injustice, slavery was the place to start: When will work be undertaken to change it, or at least to temper it? I know nothing of Governments' Politics, but they are fair, and never has Natural Law been more in evidence. They cast a benevolent eye on all the worst abuses. Man everywhere is equal. As she pointed out in January 1790, in an open letter to an (anonymous) American colonist attacking her play, at the time she wrote Zamore and Mirza, there was no organised French abolitionist movement. The Societé des Amis des Noirs did not yet exist. She ponders in that letter, whether it was her play that caused Brissot and the others to create that society, or whether it was just a happy coincidence: I can therefore assure you, Sir, that the Friends of the Blacks did not exist when I conceived of this subject, and you should rather suppose that it is perhaps because of my drama that this society was formed, or that I had the happy honour of coincidence with it. In fact, Brissot did take note of the play, and in the winter 1789, he made use of his growing influence to persuade the actors of the Comédie Française, finally to put it on. Unfortunately, the actors bore a grudge, so they arranged for the play to be put on on the last day of the year, after which Parisians would be returning to their family homes to celebrate the New Year. The contract required that a play make a certain amount of money in the first three days if it was to stay on the program. The first night was a success – but a political rather than an artistic one. People came to support it and to protest against it, and they were so loud about it, that few could hear the actors. Fortunately the text was in print, and reviewers at the time noted that they’d had to refer to the printed version to know how the play ended. Those who protested against the play most vociferously were the colonists, who had strong financial interest in the laws regarding slavery staying as they were. One such colonist wrote to Gouges, imputing that she was but the tool of Brissot’s society, and that her play was a call for the slaves of America to revolt. Gouges responded in an open letter, (1790) arguing, as we saw, that it was she, not Brissot, who’d first given voice to the abolitionist in France, and that her play did not incite revolution, but that it enjoined the French people and the colonists to see that all men were equal and abolish slavery, and the slaves to trust in the new laws and wait for a better future. Two years later, these accusations came back when the slaves and the free people of colour of Saint-Domingue revolted. According to Brissot, both the English revolution and Macaulay’s History were a significant influence on the American Revolution: The Americans lit their reason with the torch of those men, who were enlightened in a century when nobody was. It is enough to be convinced of it to read the excellent history of Miss Macaulay, and to compare what this excellent woman says about the sevellers(sic) whose principles she set out so well, to all the public writings of Americans during the troubles. Macaulay, encouraged by the warm friendship of her correpondents, and the success of her history in America decided to travel to that country, for the purpose of writing about the American Revolution. During that time she was hoping to gather material for her book, but also to find support for the publishing of it. In that, Brissot tells us, she was disappointed: She was admired everywhere she went, but no one paid a subscription for her History. Deceived in her speculation, and in the support she had excepted, she came back discgusted by the Americans. Her anger was unfounded. At peace, empoverished Americans only thought of rebuilding their farms and cultivating their lands. They only read newspaper, which, despite their cheapness, they could ill afford. Few books, aside from the Bible, were being sold in America, and if you look at the list of subcribers for Gordon’s History of America, you will be surprised to find that three quarters were English. Macaulay died shortly after her trip. One might be tempted that she would have received more support had she been a man – she could, like Paine, have become the cossetted darling of the Americans. However, Paine went to America before the war, before the Americans became strapped for cash. Brissot experienced something similar to Macaulay – when he travelled to America to find a place to settle with his family, he tried to enlish patrons, people who would help him establish himself there as a writer. He too came back disappointed.

Jacques-Pierre Brissot, Manon Roland’s close friend and republican ally, also visited England. Brissot was a lower-middle class provincial who trained as a lawyer, but came to Paris and decided to become instead a writer and journalist. One of his first jobs was for the Scotsman Samuel Swinton, the editor of the Courier de l’Europe which reported on English politics in several languages. Brissot was his French editor. It is in that capacity that he first travelled to England in 1779 at the age of 25. This first journey was short – two weeks – but it gave him a taste for England. This taste became more pronounced as the young writer came up against the stringent French censorship laws, and again when in 1782, he married Felicite Dupont, who translated English writers Goldsmith and Dodsley, and who had spent some of her childhood in London. The couple moved to London shortly after they married. Brissot, who was hoping to establish himself as a writer there was disappointed. As a foreigner, I was snubbed, he says, except by a few individuals, the principal one being Catharine Macaulay. Catharine Macaulay (1731-1791) was only fifty-one when Brissot met her. Yet, he describes her as a very old woman: Imagine a woman with lead on her face, missing teeth, wrinkles badly hidden with rouge, and whose decrepitude showed beneath her always fashionable and elegant get up. Next to her the brilliant figure and freshness and health of her husband, still an adolescent! It looked as if a child was hugging a corpse. Macaulay’s marriage to a twenty-five year old (hardly a teenager!) and good looking man had of course been badly received, and even Brissot, who admired her greatly and defends her against other accusations (such as that she was not the author of her own works) finds this difficult. But even then Brissot tries to dispel the calumnities by arguing that it was the family of her husband (his brother was some sort of medical innovator or quack) that was really objectionable. Macaulay’s most famous work was her History of England in eight volumes. Brissot thought that work remarkable, and beleived that she deserved the laurels she had taken from David Hume. To objections that she could not, as a woman, really be the author of that work, Brissot replied that the evidence that she was laid in her conversation: ‘It has all the characteristcs, he said, of the dignity, the republican energy breathed by her History.’ |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed