|

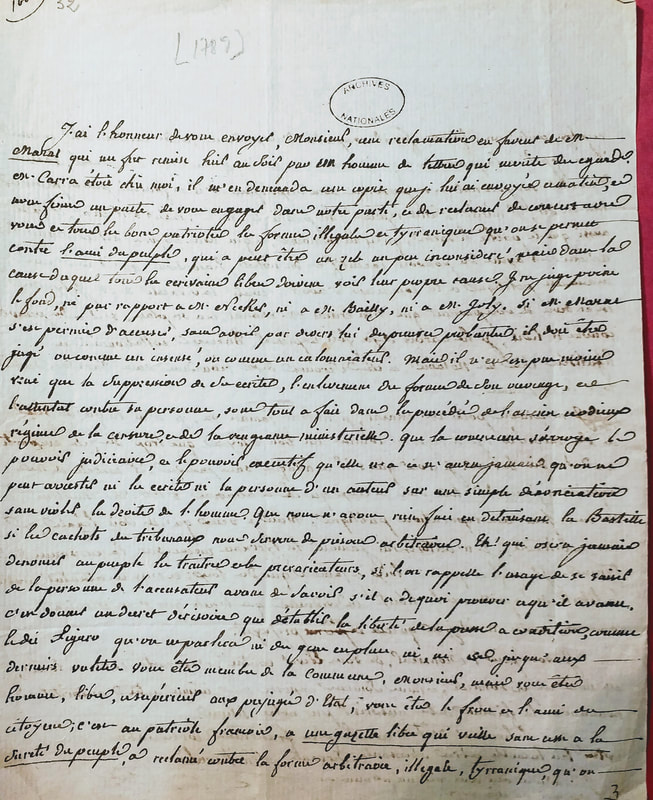

In the Archives Nationales, I found a set of letters from Louise Keralio to Jacques Pierre Brissot. The letters are kept in a folded paper, which notes that one of the letters is about Marat. The letter in question is undated, but from the reference to Marat’s denunciation of Necker means that the letter must be have been written towards the end of October 1789. Here is a – translated – extract: It is my honour to send you, Monsieur, a claim on behalf of M. Marat which was handed me yesterday evening by a man of letter who deserve our consideration. M. Carra was at my home, and asked me for a copy that I sent him this morning, and we made a pact to win us over to our side and to [?] with you and all good patriots against the illegal and tyrannical acts that have been allowed against the ‘Ami du Peuple’ whose zeal is perhaps a little inconsiderate, but for in cause all free writers should recognize their own. I do not judge of the content with respect to M.Necker, M.Bailly or M. Joly. If M.Marat allowed himself to make accusations without probable proofs, he must be judged either as a madman or a slanderer. It is nonetheless the case that to suppress his writings, and to attack his person belond entirely to the ancient and odious regime of censorship and ministerial revenge. […] One cannot put a stop to the writings or the person of an author on a simple denunciation without violating the rights of man. We have done nothing by destroying the Bastille if the tribunal’s lock-ups serve as arbitrary prisons. Louise Keralio was then already a friend and correspondent of Brissot – they had advertised each other’s journals, and praised each other’s work and ideas. Keralio had not, however, met Marat, and had only read a few articles by him. She supposes that Marat is a good citizen whose zeal has carried him beyond acceptable limits. But what she cares about is that the French Press should be treated legally, and not tyrannically. She cites Beaumarchais’ Figaro, jesting that the press should be free, provided it does not mention important people, religion, or anything contentious. She begs Brissot to use his influence to interfere on behalf of Marat, l’Ami du Peuple, and make sure that he is asked to present his proofs so that if he has them, it is known that he did not slander Necker, Bailly and Joly, and that if he doesn’t, the reputation of these three will be cleared in the eyes of all.

Marat quickly came to be regarded as a threat by the Girondins – especially after he voiced his opinion that the best way to safeguard the revolution would have been to cut off six hundred heads. He went into exile, came back, was tried, imprisoned for a month, and acquitted before he became one of the leaders of the Terror. In September 1792, he tried to have Brissot arrested. One wonders if Brissot looked back then, on Louise Keralio’s petition three years earlier, that he should stand up for Marat… Marat was murdered in July 1793, by Charlotte Corday, who’d decided that by killing Marat she could put a stop to the Terror and protect the republic.

0 Comments

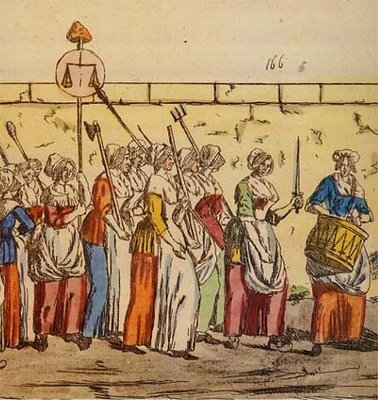

In 1789, Keralio wrote Brissot the following letter: Mademoiselle de Keralio is very satisfied by what [Monsieur Brissot de Warville] said today about the influence of women. It is very much part of Melle de Keralio’s principles that women should not make a great spectacle of themselves. […] A love of publicity is bad for modesty, from the loss of that comes a distaste for domestic work, and from idleness, principles are forgotten and from lack of morals arise all of public disorders. What did Brissot write to Keralio to make her thank him for his ‘little lesson’ and assure him at length that she did not think women should do politics? Vicky Mistacco suggests that we can guess somewhat what he said from his published response to women’s presence in the Assembly where he describes the women who walked to Versailles as 'revolting' and their entering the Assembly to deliver the King as a religious transgression. Brissot’s sexism was particularly insidious because he was a great supporter of individual women, an admirer of their work. He was close to Keralio, but also to Manon Roland, and had been very interested in Olympe de Gouges’ s work, promoting her play on slavery, and invited her to join his Society for the Friends of the Blacks. When such an ally also argues, politely, with restraint, that women should not do politics openly, then it is difficult not to listen. We are often led to wonder why a person who is politically sound, and who is apparently unthreatened by strong and talented women, can turn out to hold sexist views. In most cases, we have no way of knowing. But Brissot, in the Memoirs he wrote in the prison de l’Abbaye (in the cell Manon Roland had just vacated, and where she’d begun her own Memoirs) gives us an insightful account of his own sexism. He describes his attitude to politically engaged women in 1782, when he was visiting Geneva. Because it is such a rare moment of clarity coming from someone who was sexist, I reproduce it entirely: […] politics seemed a heavy and boring science, unsuitable for a pretty woman. To please and to entertain was the great art that women were to learn their entire life. And if the philosophy I professed forced them to take up other studies, it was of the virtues that could render a wife or a mother’s company useful and pleasant for her spouse and children. In a word, a woman given to politics seemed to me a monster, or at least, a new kind of ‘precieuse ridicule’.” So Brissot tells us that his views were absurd – he might have said they were also harmful, dangerous, even. And he attributes them to a weaker commitment to the truth than was needed, but also to his fashionable love for Rousseau – either way, he was carried by the whirlwind of prejudice.

Louise Keralio, historian, novelist, and journalist has been accused of sexism because of her emphasis on domestic virtues and political silence for women. (She has also been accused of misogyny because of an anonymous tract that we have no reason to think she wrote The Crimes of Queens). * Keralio emphasizes that women have a duty assigned them by nature to prefer domestic work to politics, and that this is essential to the well-being of the nation. In a letter to Brissot she wrote: A great love of publicity harms modesty. And from the loss of this great good comes distate for domestic work, and from lack of work, the forgetting of principles, and from loss of morals, all public disorders. But Keralio was definitely also of the opinion, at least in 1789, that France could only gain from letting her help shape the revolution. And she did not wait to be asked, but started a newspaper, Le Mercure National. Before that, she had been working on an anthology project, intending to publish forty volumes of works by French women writers, starting from Heloise. She had to give up after 6 volumes, due to lack of funds. But what she says in the early volumes is significant. Her account of Heloise, in particular, sheds light on her own ambitions. Heloise, she says, was a natural genius, superior in intellect to everyone of her contemporaries, regardless of sex. Yet, there was another account of Heloise from a strong influence on Louise Keralio: Rousseau’s. Rousseau’s heroine, in Julie or the New Heloise, starts off, like the real Heloise as the bright student of a philosopher. But when she discovers her true purpose, domesticity, she gives up all thoughts of feeding her intellect and devotes herself to her children, husband, and the neighbours, becoming the guarantor of virtue and stability at home and in the village. We tend to think that the shackles of domesticity have always held us back, that we are fighting the same gender stereotypes that our foremothers fought, from prehistoric times onwards. That we are fighting stereotypes is true, as it is that we are fighting off male domination. But the stereotypes were not always what they are.

In the 18thcentury, women were not necessarily thought of as ideal mothers, or virtuous wives. This is something that came from Rousseau, who revived the ideals of motherhood (making sure also that it couldn’t reach too great heights). This, as also his claim that mothers should feed their children themselves instead of employing the services of wet-nurses, was felt as liberating by some women. They were given a role in society that they didn’t have before. They were no longer just an extra pair of hands in the family business, or an ornament for the rich. They were the guarantors of virtue in the home and the republic. So it's no great wonder that a woman like Keralio who admired both the historical Heloise for her intellect and Rousseau’s New Heloise, for the advance in women’s place in society she represented at the time, appears somewhat muddled to 21th century feminists! * Thanks to Vicki Mistacco for sharing her research on Louise Keralio, and in particular for pointing me toward the letter to Brissot and the influence of Heloise of Argenteuil. In 1788, when he first presented his ‘What is the third estate’, the Abbé Sieyès declared that : “inequalities of sex, size, age, colour, etc. do not in any way denature civic equality” (Sieyes, Political Writings, 155). These, he said, like inequality of property, are incidental differences and cannot affect civic rights. But Sieyès, it turns out, was not so committed to equality, however, that he wanted to extend rights active citizenship to women. In his Préliminaire de la Constitution, written on 22 July 1789, he writes: All of a country’s inhabitants must enjoy the rights of passive citizenship: all have the right to the protection of their person, their property, their freedom, etc. But not all have the right to take an active part in the formation of public powers, all are not active citizens. Women, at least in the current state of things, children, foreigners, those that contribute nothing to supporting the public establishment must not actively influence the republic. Women did not remain silent. Then journal editor, Louise Keralio, responded four weeks later: We don’t understand what [Sieyès] means when he says that not all citizens can take an active part in the formation of the active powers of the government, that women and children have no active influence on the polity. Certainly, women and children are not employed. But is this the only way of actively influencing the polity? The discourses, the sentiments, the principles engraved on the souls of children from their earliest youth, which it is women’s lot to take care of, the influence which they transmit, in society, among their servants, their retainers, are these indifferent to the fatherland?... Oh! At such a time, let us avoid reducing anyone, no matter who they are, to a humiliating uselessness. Keralio is clearly angered by Sieyès’ formulation: in what sense are women not active, she asks? What is there of passivity in the work they conduct from the home, nurturing republican values and giving birth to new citizens? Like Manon Roland, she was a reader of Rousseau, and was convinced that there was a place for women in Republic that was central to the flourishing of the nation, even though that place was in the home rather than in the assembly. So she does not disagree with Sieyes that women should stay home, rather than participate in debates taking place in public fora, but she believes that the home is just as important a place for the making and cultivating of the republic than the assembly. Olympe de Gouges’s famous response was printed at the same time as Louis XVI ratified the constitution drafted by Sieyès, in September 1791. Man,” she asks “are you capable of being fair? A woman is asking: at least you will allow her that right. Tell me? What gave you the sovereign right to oppress my sex? Your strength? Your talents? Observe the creator in his wisdom, examine nature in all its grandeur for you seem to wish to get closer to it, and give me, if you dare, a pattern for this tyrannical power. On behalf of women in general, she expresses her outrage that women have been exclude from active participation in the city, with no argument, other than that they belonged to the class of those who ‘contribute nothing to supporting the public establishment’. Women, she knows, contributed both physically – by fetching the royal family from Versailles – intellectually – by debating new ideas in circles and political societies, publishing pamphlets proposing reforms (such as her proposal for a voluntary tax) – and materially – by giving money and jewels to relieve poverty and help pay off the national debt. Unlike Louise Keralio, she does not even feel that she needs to appeal to women’s contribution to the republic quamothers. Yet, she does not hesitate to remind the public that women are also mothers: Mothers, daughters, sisters, representatives of the Nation, all demand to be constituted into a national assembly. Given that ignorance, disregard or the disdain of the rights of woman are the only causes of public misfortune and the corruption of governments [they] have decided to make known in a solemn declaration the natural, inalienable and sacred rights of woman; this declaration, constantly in the thoughts of all members of society, will ceaselessly remind them of their rights and responsibilities, allowing the political acts of women, and those of men, to be compared in all respects to the aims of political institutions, which will become increasingly respected, so that the demands of female citizens, henceforth based on simple and incontestable principles, will always seek to maintain the constitution, good morals and the happiness of all. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed