|

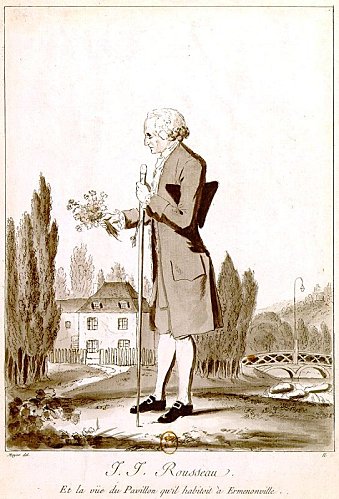

Every year for Christmas and New Year we dread the loss of the celebrities we love, and reminisce those who died during the year. Apparently it was very much the same in Eighteenth century France, if Manon's letters are anything to go by. On 2 January 1777, she wrote to her friend Sophie Cannet: Rousseau is not dead. He did not take a fall, as it was reported, and was not even even ill. I would have been annoyed had he disappeared before I got to see him. Were it not for certain troubles I cannot seem to shake, there are some things I might try, I would not write, as his wife refuses to accept that I am the author of my own letters, but... but... I must leave such projects to a later time. Unfortunately Manon never got to put these plans into action as Rousseau did die a year and a half later. On 6 July 1778, she sent the news to Sophie's sister, Henriette: Jean-Jacques is dead. I was given the news yesterday at dinner. Immediately, I felt my appetite disappear, my stomach tighten and heave at the thought of eating anything. Why? ... The best of Rousseau stays with us; anything else is but released from pain. His life is filled, his spirit and his sentiments are still here, so why am I so saddened?

0 Comments

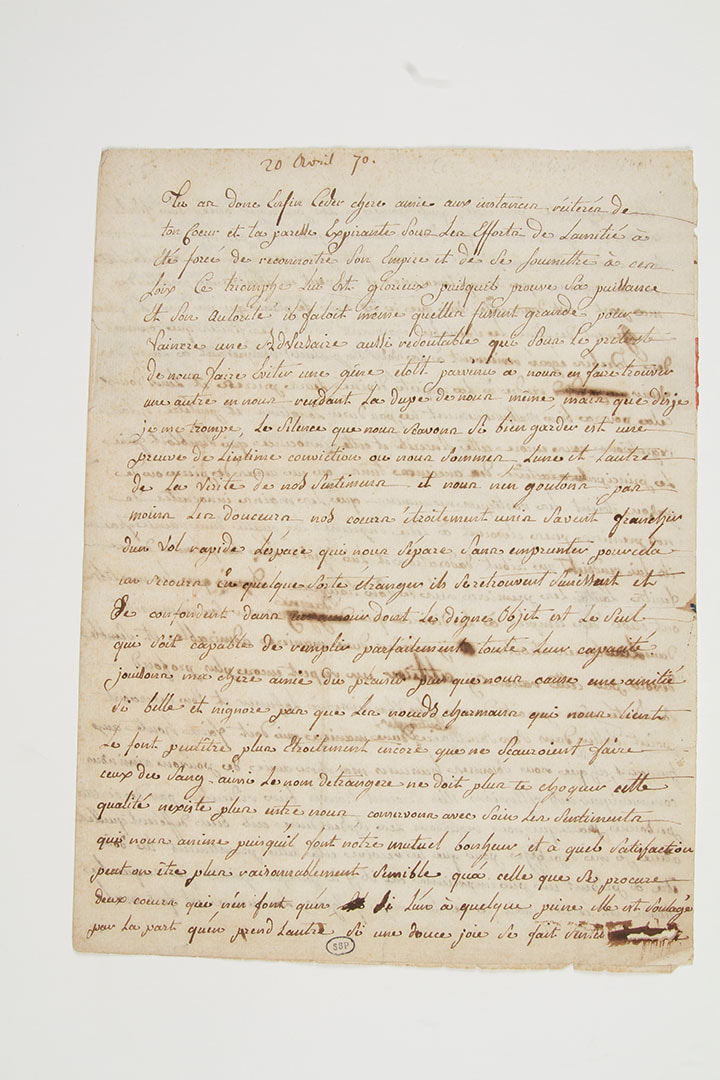

In the winter 1776, Manon Phlippon was 22. She lived alone with her father in Paris on the Quai de l'Horloge, - she had not yet met her husband, Jean-Marie Roland - and she spent much of her time writing in her room, letters or essays in political philosophy. Late on Christmas eve, as the revellers were going home, she wrote a letter to her close friends, Henriette and Sophie Cannet.

25 December 1776, 1am

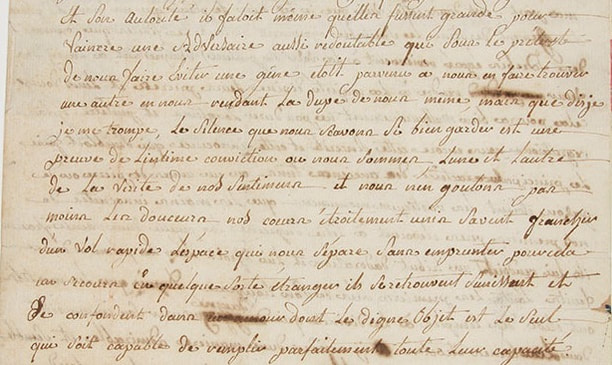

As you can see, I am not gone to the midnight mass. I would have gone, as I think it is important to set an example even when one doesn't want to do it for oneself. But the weather is frightful, my father did not think it a good time to be devout, so without a fuss we stayed home. You might find it strange that I should write always at the first hour. Let me tell you a something of my daily y life which will give you insight into how I spend my time. I never get up, this time of year, before nine. I spend my morning with the housework. In the afternoon, I do needlework and I dream, building everything I fancy in my mind, poems, arguments, projects, etc. In the evening I normally read till dinner time, which is uncertain because it depends on when the master comes home. He is out at all times exept meal times, without telling me, or caring for any of his affairs, and too often leaves me to deal with those who come to do business with him. He usually gets home at half past nine, but sometimes ten or later. Supper is soon over, since when there are few dishes, one eats fast and there is no conversation no feast can last long. In between dishes, I always attempt conversation but my attempts are foiled by his careless replies. I am always trying to hold a thread; but though I do my best, it is always in vain. Eventually time passes and it is eleven. My father throws himself in his bed, and I go to my room, where I write two or three. In August 1782, Manon was in Amiens, while her husband, travelling for business, was in Paris. Jean-Marie Roland was inspector of Commerce and Manufactures, had his office in Amiens. The couple lived there for the first four years of their marriage (1780-1784) and their daughter was born there in October 1781. Most of the time, the couples were working on an Encyclopedia of textile manufacture, gathering expert articles, researching and writing, and editing. When Jean-Marie was promoted to general inspector, the family moved to Lyon, and Manon was able to live in the family's nearby country home, Le Clos. Whenever they were apart, the couple corresponded. On 8 August 1782, Manon wrote to Jean-Marie: I hear, my friend, from M.d'Antic, that you are arrived, and while at first I only meant to let you know through him how pleased I was, I thought that at the same time I should pass on to you the included, which is from Villefranche where you must reply. It came together with a piece for Despreaux, from the lawyer Dessertines who disserts on Greek chronlogy as an ex-jesuit. (Please don't tell the chanoine this is from me, as it talks about the Deluge, and Moses, etc, things and people I don't wish others to think I have fallen out with). Monsieur d'Antic was Bosc d'Antic, who, after 1789, went only by Bosc. He was a close friend of the Rolands, a botanist who helped them in the botanical part of their Encyclopedia. The 'chanoine' was Roland's brother, a religious man. Both Manon and Jean-Marie were atheists, but Manon liked her brother in law very much and did not wish to argue with him too loudly. As to the young lady, the editor of the letters refers to Manon's childhood friend and correspondent, Sophie Cannet, who introduced her to her husband. Sophie was considering an offer of marriage from a much older man. She eventually gave in, and a few years later was a widow with two children. Letter from Manon Phlipon (Roland) to Sophie Cannet in 1770. (Lot 33o Bilbliorare)

|

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed