|

While we continue to investigate the lives, deeds and works of the great women of the French Revolution, let's not forget that some of these women were married, and that their husbands sometimes also contributed to the political events of their times. This is not, sadly always the case, and sometimes, what we have are rather petty disputes between men who were not as good at their jobs or deserving of their honour as they might have been!

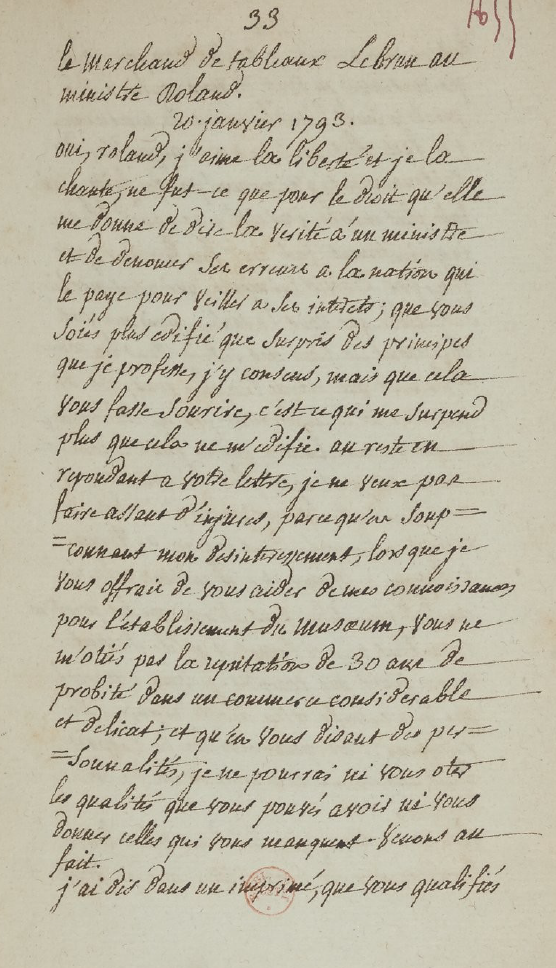

This is partly true of an exchange between Jean-Marie Roland, Manon's husband, and Charles Lebrun, husband to the celebrated painter Elizabeth Vigee-Lebrun. Lebrun was an ambitious art-dealer, supported entirely by his successful wife's earnings and works. However, Vigee Lebrun, who was Marie Antoinette's favorite portraitist, had gone into exile in the early days of the revolution. When she left, she took only 80 louis with her and left most of her fortune with her husband. While abroad she worked and continued to send her some of her substantial earnings to Charles. In order for that money not to be confiscated, Charles asked for a divorce – this was on paper only, and married life resumed as soon as she returned from her 12 year exile. Jean-Marie Roland was minister of the interior – but we know that a lot of his decisions were made by his wife, and that she wrote several influential letters for him. The two husbands came to fight over the question of how to look after the art confiscated from the aristocrats and the clergy. Lebrun thought he should be given the job and paid handsomely to do it. Roland thought this was not a priority. Lebrun published a pamphlet which Roland found insulting and even threatening, and Lebrun responded with an epistolary meltdown, accusing Roland of not being a true republican. I owe the details of this story to Bette W. Oliver's book, Surviving the French Revolution (chapter 4). Here is the first page of Lebrun's letter below, courtesy of Gallica

0 Comments

When Brissot decided that he would set up his republican colony in France, rather than America, he first approached his friends Bosc and Lanthenas. The latter had some money and was enthusiastic about the idea – although he might have preferred the original plan of going to America. Bosc and Lanthenas suggested the include the Rolands in the plan. Their current way of living, between Lyon where Roland worked, and their idyllic country house, le Clos, together with their shared republican dreams made them perfect for the project. Brissot was introduced, and the friends corresponded. It was decided that they would contact a few others and try to put together enough money, in installments, to buy land and set up the colony. Brissot drafted a plan for what he called an agricultural society, or society of friends. The aim of the society would be twofold: to ‘regenerate’ its own members by cultivating the earth, and to regenerate the local community through a ‘rural education’. The first part of the plan would be to buy property, a land vast enough to house twenty families, each in its own simple and luxury free house, and with room to grow. The land should be in the countryside, contain a wooded area, water, be close to a mountain, and served by a large road. The plan says nothing about how the rural life would help ‘regenerate’ the members of the society. Maybe he felt there was no need, and that anyone interested would already believe in the healing powers of the simple, rural life. This was certainly true of Manon, who even before she was married, and while she still lived in Paris, claimed that the Spartans led the best lives, because they lived in the country, simply, without any luxury. She embraced, and sought to reproduce, whenever she could, the life led by Rousseau’s Julie at Etanges, simply, luxury free, industrious, and always with an eye to the needs and education of the men, women and children working the land she lived on. At le Clos, she even participated in the Vendanges when the season came, picking grapes alongside her peasant neighbours, making friends with them and treating them as equals. When the Great Fear happened, and those who had locked their doors against those who did not, she was secure enough in her relationship with the poor of Le Clos not to run away. Another reason why Brissot may not have felt the need to explain what was in it for the colonists lies in the title of the document in which he details his plan: a society of friends. Brissot had ties with the Quakers of England, whose philosophy and way of life he admired, and when he travelled to America, it is the Quakers he sought, both because he regarded them as a model and because of their work against slavery. His brother in law had immigrated to Philadelphia, a Quakers town, so there were possibly ties to the sect from that side of the family too. Another possible clue to Brissot modeling his proposal on Quakers communities is the content of the educational program the colonists were to dispense to the locals – one in which religion was taught but in very simple, rational terms. Members of the society, when they were not labouring the earth, or reading philosophy, would teach peasants ‘the purest morals, the simplest religious beliefs and how to work with their hands.’ Although the colons were to live simply one thing they would not have to compromise about was reading materials. Brissot takes care to specify in his plan that the colony will house a good library held in common. Should we talk about a colony when they were in fact not planning on leaving the country? It seems so – and moreover that what they intended was a colony in the strong sense, i.e. they wanted to colonize the people living around them, teach them to be other than they were, more virtuous, more efficient in their work, and better republicans. But at the same time they had no intention of living among the peasants as equals, or of integrating the peasants more closely into their communities. The community was one of teachers, who would benefit from a more rural lifestyle, but not peasants. Agriculture and philosophy might live side-by-side, but not together. This separation of status between the colonists and the colonized is reflected in Jean-Marie Roland’s letter to Champagneux in early 1792 – by which time all the land had been bought and all had given up on the dream: I was as sure of this as my existence - to create a monument to patriotism and the useful arts, such as does not exist even in Paris [...] we would have made a community such as never existed before in the provinces, which could have become famous and would have rewarded our pains with either reputation or profit. Perhaps this was not Brissot’s intention, but it seems that for Manon’s husband at least, there was a third aim, beyond self-improvement and improvement of the local peasantry: fame and wealth for the founders.

In 1788 Brissot travelled to America in order to investigate the possibility of removing his family there, and also in order to try and make himself known: Brissot did not wish to give up his literary career, and if he were to move to a large unknown country, he would need the support of influential people. In that sense, his trip was not successful – he did not feel he had made enough of an impact to risk moving his name and career to the other side of the ocean. But the dream remained. When he wrote up his travel notes, which were published in 1792, he emphasized what he saw as the parts of American life worth reproducing: the Americans, he thought, lived well because their lives were simple and virtuous, and everything in it arranged according to reason. This was the dream he was after, and with which he infected his friends, the Rolands, Lanthenas, and Bancal. In a sense, it may have seemed safer to stay than to go. Those who moved to America, taking advantage of the dubious Scioto company, selling worthless land in Ohio, tended to be those who had either tried to make a life for themselves in France and failed, or those who had little hope of succeeding where they were. FelicitéBrissot, writing to her brother in Philadelphia, warns him of the possible arrival of several men they know, and of their various moral failings – one is selfish, another stupid, and a third so bad tempered that he has alienated everyone who could help him. She adds, charitably, that they are young and that therefore they may benefit from the move, but worries nonetheless about the effect of these men on the American communities (in particular the one she thinks of as intellectually limited, because he would, she thinks, encourage gossip). For those who care about the future of France, and who think that they are in a position to benefit the nation through their character, ambition, knowledge, then it is best that they stay and attempt to bring the American model to the new Republic, rather than draining it of its most promising elements in order to join those it has already rejected. Towards the end of 1789, land and building that had belonged to the church were put for sale to private buyers, as a way of reducing the national debt. This was an opportunity for Brissot to put his plans for a colony into practice without leaving the country. There were several reasons why that may have seemed like a good plan to him. First, his trip to America had not been the personal success he had hoped it would be, so that if he moved there, he would not be known as a writer, and could not count on the help he would surely need to establish himself in that profession. Secondly, France was now a desirable place to be for the reason America was: it was on its way to becoming a Republic, a land of freedom. Brissot first approached his friends Bosc and Lanthenas. The latter had some money and was enthusiastic about the idea – although he might have preferred the original plan of going to America. Bosc and Lanthenas suggested he include the Rolands in the plan. Manon Roland became the prime mover behind the plan, which, unfortunately, was never realized.

Until a few weeks before she died, Manon Roland didn't want to publish in her own name. But she did publish either anonymously, or under her husband's name, 'helping' him with his work: "For twelve years of my life, I worked alongside my husband, as I ate, because the one was as natural to me as the other. If some part of his work was cited, because it was found to be more gracefully written; if some academic trifle such as he liked to send out was accepted by one of the learned societies he was a member of, I was happy for him, and I did not take particular notice whether the piece was one of mine. And often he ended up persuading himself that he had been on a particularly good streak when he'd written this or that passage which in fact came from my pen. [...]" When Roland was named minister of the interior, she kept on writing for him. She found it easy as 'she loved her country' and was 'enthusiastic for liberty'. Only once, she tells us, did she allow herself to be amused by her ghostwriting, when she penned a letter from the minister to the Pope, demanding the release of French artists imprisoned in Rome. #ThanksForTyping |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed