|

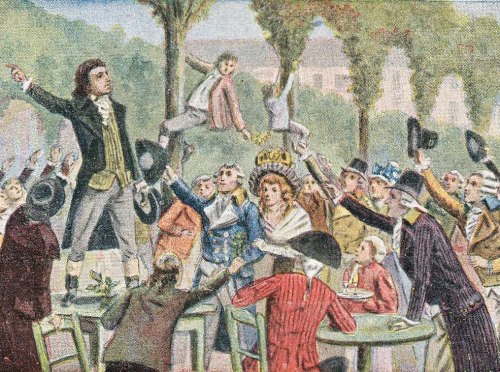

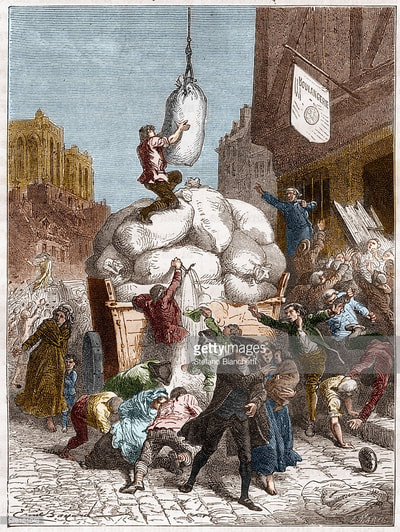

Although Madame de Stael is well known, as a historical figure and a writer, she remains very much in the background of the research I have conducted so far on the women of the French Revolution. I mentioned Roland's quip about her salon in my last post. This is as close as the two women got. Stael and Gouges never met, and although she and Grouchy moved in similar aristocratic and international circles, they were certainly not friends. Germaine de Stael was the daughter of Jacques Necker, a Swiss banker appointed by Louis XVI as finance minister in 1777. Necker held this post until 1781, when he was dismissed for having hidden the debts of France in his reports. He was recalled briefly in 1788, but dismissed again on 12 July 1789. Camilles Desmoulins, in the famous speech rousing the French people to revolt, invoked the King's treacherous treatment of Necker. Necker comes across as something of a quiet hero of the revolution, a man who did his best to resist the decadence of the French regime and serve the people. This is certainly how his daughter saw him. However, to see him as such we must leave out the story of how he became minister in the first instance. In 1776, Turgot was minister of finances, and Condorcet, director of the mint, his right hand. This was a difficult period for the French economy, marred by the flour wars, the rising price of grain which resulted in famines, and the ensuing revolts. Turgot attempted to deal with the crisis by getting rid of a number of regulations (including pricing) which had a throttling effect on the production of bread. But before he could succeed (or fail) he was dismissed and replaced by Necker. People in Turgot and Condorcet's circle believed that Necker had had a hand in his dismissal, privately misrepresenting to the King what Turgot was doing. Condorcet, when Turgot was dismissed, did not want to continue in his position. But the King ordered him to stay. This background of political squabbling may explain why Grouchy and Stael never became friends. Each was loyal to her husband or father. The rift grew bigger when the Condorcet's close friend and ally, Mirabeau took over from Necker in the heart of the French people. Necker left France, and after 1789, had no role to play in revolution. Stael fled Paris in 1792, after the September massacres, and took her salon to her chateau in Switzerland. When Napoleon came into power, he took an instant dislike to her, and she had to exile herself again. As powerful figures in French literary circles, however, Stael and Grouchy could not ignore each other. And when Grouchy's Letters on Sympathy came out in 1798, Stael wrote to her, admitting that she envied both her style and the depth of her analysis. It is not clear whether Sophie de Grouchy took the homage seriously.

Wilhelm von Humboldt, who visited Sophie in 1799 reported the letter in his Journal Parisien. "She showed me a letter which Madame de Stael had written about her book to which she gave exaggerated praise"

0 Comments

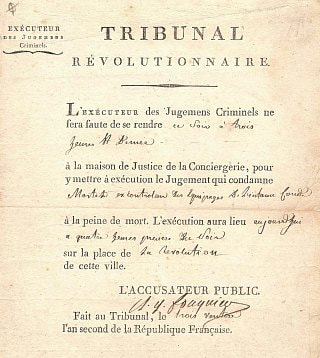

We hear tales of Madame de Stael that she is always at the Assembly, where she has admirers to whom she sends notes from the gallery to encourage them to vote for patriotic motions. They say that the Spanish ambassador has reproached her for this at her father's table. You cannot imagine how much weight the aristocrats give such nonsense - that was born from their own brains perhaps. But they would show up the Assembly as led by a handful of scatterbrains, excited and fired up by a dozen women. In contrast to her aristocratic contemporaries, who hosted the whole of revolutionary Paris in their rich salons, serving champagne and entertaining with music and literature, Manon Roland had the reputation of being a rather prim hostess. The only drink she served was sugared water, and she invited only her husband's colleagues, all men. She herself would sit apart from the men, sewing at her table, listening without talking. Manon did visit with other Girondin women, such as Madame Petion, Madame Brissot and Louise Keralio-Robert. She even frequented Helen Maria Williams, and through her Mary Wollstonecraft. Her objection to women was not on the grounds that they should not participate in political debates, but because she thought that the public was not ready to accept politicised women, and because she worried that the aristocrats would use women's presence in her salon as a way of ridiculing the revolution as they had done with Madame de Stael in 89. On 6 April 1791, she justified herself on this point to Bancal: Our customs do not yet permit women to show themselves publically. They must inspire goodness, ignite all the sentiments that are useful to the nation, but not appear to participate in political work. They will only be able to act openly once every French man will have earned their freedom. Until then, our lightness, our poor morals would turn to ridicule everything they would seek to accomplish, and thereby destroy all the advantage that was to result from it. Olympe was tried at the Conciergerie on 2 November 1793. After she was arrested on 20 July she had been held first, at the Prison de l'Abbaye, transfered to the hospital prison of La Petite Force - she was suffering from an infected cut on her leg - and finally she paid to be incarcerated at a private pension on Chemin Vert. The public prosecutor of the Revolutionary Tribunal was Antoine-Quentin Fouquier-Tinvinlle, a zealous and ruthless officer of the Terror, who took his turn at the Guillotine in 1795. Olympe was introduced as 'Marie Olympe de Gouges, veuve Aubry. born in Montauban, aged 38 (she was in fact close to 45), residence: rue du Harlay section du Pont Neuf'. She was charged with' having composed a work contrary to the expressed desire of the entire nation', and according to Article 1 of law of 29 march 1793: Whoever is convicted of producing writings advocation for the dissolution of national representation [...] will be sentenced to death." she was sentenced to death by the guillotine. She would have been excecuted on that same day, but, after the order was read, she announced that she was pregnant. 'My enemies will not have the glory of seeing my blood flow. I am pregnant and will bear a citoyen or citoyenne for the Republic' According to the law, she was to be examined by health officers who had been named by Robespierre 8 months previoulsy, after the Revolutionary Tribunal was founded, and by a Midwife, Veuve Prioux. Her cell at the Conciergerie was the same one Marie-Antoinette had been held in after her attempted escape. It was isolated, for the purpose of keeping prisoners 'au secret'. The infirmary was just outside that cell, a dire place, if we are to believe the description of a surviving prisoner, Beugnot: Seven by thirty metres, closed on both sides by iron fences, two narrow windows, vaulted roof, like some sort of gothic hell. 40 or 50 dirty straw beds on either side, with two or three patients each, sharing unwashed blankets. The privies were in the middle of the infirmaries, and there sick patients who had collapsed on the way lay in their own waste. The corpses, three or four each day, were removed at a specific hour of day, and until that time, the dead remained in bed with the sick. All that is now left of this room is one of its narrow windows, which is visible from the women's courtyard. The medical team concluded that if Olympe was pregnant, it was too early to tell. Fouquier-Tinville chose to ignore their doubt, and declared that her claim had been found to be false: The Public Prosecutor notes that the accused was incarcerated for the past five months and that according to regulations no contact was allowed between men and women in prisons. Therefore she made it up in order to avoid the death penalty. There was in fact much romantic commerce between prisoners, as they were kept in adjoining wards, and often not very efficiently. In any case, Olympe had been staying in a private pension for mixed prisoners, a fact that Fouquier Tinville chose to ignore.

|

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed