|

Equality is not often discussed in a republican context, as liberty is more central to that debate. But equality also plays a role in 18thcentury republicanism ‘Liberty, Equality’ was the first motto of the French Revolution. Republican liberty is all about non-domination: living under a despot, a king, is being dominated even when the King is not intentionally harmful. The very fact that one person is in a position to interfere with the lives of all on a whim is tyranny, and results in the absence of freedom. Republican equality is also defined in contrast to tyranny. It is equality of status in relation to the law that prevents one individual from being dominated by another. This was framed early on in the Revolution by Abbe Seiyes in “What is the Third Estate”: I picture the law at the center of an immense globe. All citizens without exception are at the same distance from it on the surface and occupy equal space. All equally depend on the law; all give it their liberty and property for protection. This is what I call the citizens’ common right, whereby all are alike. [...] If [...] one person comes to dominate his neighbour, or to usurp his property, the common law will repress his attempt. Emmanuel Joseph Sieyes (1748-1836), pictured with and without his religious garb. Equality of status must have seemed especially urgent for the women involved in the Revolution, as they must have understood that without that, they could not claim the freedom that was on offer as they would remain under the domination of their husbands. And in 1788, it looked as though they would benefit from the title of citizen and therefore receive equal status. Sieyes, when asked who would count as equal replied that “inequalities of sex, size, age, colour, etc. do not in any way denature civic equality”. These, he said, like inequality of property, are incidental differences and cannot affect civic rights. One good place to start in establishing republican equality, one place where it was very clearly wanting, was the criminal law. Sieyes called the use of privilege in punishment an ‘abominable distinction’: Why do the privileged, when they commit the most horrible crimes, nearly always escape punishment, thereby stealing from the public potentially most effective examples? [...] The law dictates different sentences for the Privileged and he who is not. She seems to follow the Noble criminal with its tenderness, and to want to honour him even at the scaffold. Two years after Sieyes wrote ‘What is the Third Estate’, and when it became clear that sex would make count towards equality after all, Olympe de Gouges argued, along similar lines, that for women to have equal status as citizens would mean in the first instance, equal status in the face of criminal law: VII. No woman may be exempt; she must be accused, arrested and imprisoned according to the law. Women, like men, will obey this rigorous law.

0 Comments

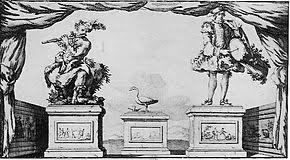

Eudora (1781-1858) was born one year after Manon married Roland de la Platiere. The pregnancy and birth were reasonably straightforward and Manon elected to feed the baby herself, following Rousseau’s advice in Emile. When she thought her milk had dried, she turned to her husband for advice. He visited an orphanage and reported that infants there were fed beef stock mixed with cow’s milk, dripped through a sponge. Fortunately for Eudora, her mother’s milk had not in fact dried. Once she was a little older, her parents decided that it was safe for her mother to travel – she had family business to attend to in Versailles – and to leave Eudora in the care of her father. In a letter he reported that he let her play on the floor of his study while he worked, and that she had somehow gotten hold of a pair of scissors and some of his socks, which resulted in pretty red ribbons. By the time they moved to Le clos in the mid 80s, the couple devised an educational program for their daughter based on Rousseau’s works. Conveniently, they must have forgot that Rousseau’s educational precepts only really applied to boys! In any case, Manon was not impressed with her daughter’s intellect and she wrote to her husband: We mustn’t pretend, your daughter is sensitive, she loves me, she will be sweet, but she does not have a single idea... [...] no promise of any wit. She embroidered a pretty work box for me and she seems good with a needle, but she doesn’t appear to have any taste, and I am starting to believe that we should not expect too much of her. When Manon was taken to l’Abbaye, in May 1793, her daughter stayed behind with the family’s servant, Marguerite. While in prison, her mother arranged for their friend, Bosc, to be her guardian in the event of hers and her husband’s death. And the even did come a few months later. Bosc took charge of the twelve year old’s education. A year and a half later, they were considering marriage. Bosc, in a letter to a friend, represents it as her idea, but one he is considering as he finds so ‘promising’ and ‘interesting’. Nonetheless the marriage does not happen and Eudora is adopted by another friend of her mother’s Champagneux. The latter, a family man, cannot take the child for himself, but he married her off to one of his son. Eudora was 15 and he husband, Pierre-Leon, 20. The couple had two daugthers, Zelia (1799-1880) who had herself had three daughters and one son and Malvina (1800-1834). It is likely that there are descendants of Zelia still alive, but I have not been able to trace them. When Malvina died suddenly at the age of 34, her mother turned to religion and became a recluse. Bosc gave Eudora her mother’s papers around that time. but it was Zelia and her children who later re-discovered Manon’s life, works and correspondence. They collaborated with Faugere to publish a new edition of the Memoirs, and donated the manuscripts to the Bibliotheque Nationale de France. Many of these can now be read on Gallica. I have written before about historians' treatment of the women of the Revolution. But it seems to be a theme that keeps on giving. The latest culprit is Max Gallo, French historian and Academician (we also saw how those were not as woman friendly as they might be). His first volume of a popular history of the French Revolution says very little about the women involved in the events between 1788 and 1793. There is no mention of Olympe de Gouges, which is suprising as much of the book deals with the people of France's unwillingness to do anything substantial about povery, and Gouges was influential in bringing about some kind of a solution by encouraging women artists to give their jewels to a patriotic fund. The last part of the book, dealing with the King's trial could also have mentioned Olympe's various writings on the topic, including her offer to serve as the King's advocate. Sophie de Grouchy is mentioned in passing as hosting a salon (but as Madame de Condorcet). But it is the treatment of Manon Roland which left me reeling. Gallo writes that Danton is weary of his enemies, the Girondins, especially: this Madame Roland, hounding him with her hatred, perhaps simply because he was not affected by her charms, and she is an imperious seductress, who imposes her ideas on her husband, on Barbaroux, Brissot, the leaders of the Girondist party. We should not assume that Gallo has not read Manon Roland's works, however. He clearly has and quotes one of her letters, written after the September massacres: My friend, Danton leads all ; Robespierre is his puppet; Marat holds his torch and dagger. Except that Gallo omits to attribute the quote to its author, putting it down instead as a popular rumour. During the summer 1791, when the royal family had escaped from their enforced Parisian home, been arrested in Versailles, and brought back to Paris, the Condorcets, together with Thomas Paine and a few others, and with the help of Brissot, had started a journal, Le Républicain. Sophie wrote two pieces for that journal, one of which was a satirical piece titled ‘Letter from a young mechanic’. The letter proposes that the royal family and its entourage be replaced by a set of automata. Even though such machines are expensive, it says, they will cost a fraction of what the French people are spending on their actual king. And what's more, the mechanical king, far from being a tyrant, will raise its pen and sign everything its government wants it to! Jacques Vaucanson, the putative teacher of the fictional author was a famous inventor, and one whose inventions Condorcet had praised in his works as an example of the sort of technical activity that could be just as inspirational as theories. Automata were generally meant to be humourous, rather than impressive scientific inventions, or serious art. Vaucanson had created many impressive moving statues, including that of a musician who could play twelve songs on two sorts of flutes. But his most celebrated piece was a copper duck that could be made to pick grain, swallow it and defecate them. Vaucanson claimed the duck could also digest the grain – this however, was discovered to be untrue in an autopsy conducted in 1844 – the ‘excrement’ was simply stored in a different part of the duck’s body, not metabolised from the grain it swallowed. Given this, the idea of the King and his family being replaced by automata is not simply insulting in that it reduces them to impotent machines: it is also ridiculous: the royal family, though they were used to perform their private functions in public, did not do so on demand! The King would also have been pained, no doubt, by the memory of a previous attempt to liken him to a mechanical puppet. In 1777, a pamphlet was published – The Mannequins, telling the story of a bad King who one days wakes up and finds himself, his family and his entourage transformed into puppets, whose strings are pulled by another, but more autonomous puppet of the name Togur (a thinly veiled reference to Turgot).

|

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed