A most fashionable way of thinking about politics in the 18th century, was to hypothesize what life would be like without any form of political government, and argue that it would intolerable, so that no matter how badly off we might be in this world, in a world without government, we would be worse off. This relied on the assumption that in the state of nature, we would be unhappy. As Hobbes famously put it, life in the state of nature would be 'nasty, brutish and short'. Rousseau is often portrayed as disagreeing with Hobbes on this. After all, the savage human being for him is carefree and happy, living in a land of plenty, and has no need for war or strife. But even Rousseau believed that as soon as one human being meets another, they become enemies, compete and war against each other. The only way out is civilization and government. One writer stands out in disagreement with this pessimistic view of humanity in its 'natural' state - or rather she would stand out if she were still read. Olympe de Gouges wrote a short philosophical treatise in 1788, in which she argued, against Rousseau, that human beings in the state of nature would have been, not only happy, but quite capable of living with each other, collaborating on projects and forming lasting loving relationships.

What does she base her belief on? Her own childhood experience of a simple, free and outdoors upbringing. In Le Bonheur Primitif, she speculates on the daily lives of the people Rousseau calls 'savages'. She surmises, for example, that the way in which the first breads were made may have been similar to how she was making bread as a child, laying the dough on hot ashes, and remembers how pleasant that experience was. This, she claims, gives her an insight into the lived experience of primitive people.

0 Comments

In 1798, Sophie de Grouchy published her Letters on Sympathy. We know that she already had a draft in 1791, which she'd sent to her friend Dumont for feedback that never came. We know that the Letters were complete in 1794, and that they had a title, as Condorcet refers his daughter to them in his Testament. So why were they only published in 98? We don't know as she did not leave an account. But it's likely the answer lies either in need, opportunity or both. After the Terror, Sophie needed money, and she decided to translate Smith's Theory of Moral Sentiment. Smith was very popular, and existing translations of this text were not particularly good, so there was a clear gap in the market. This also gave her the opportunity to publish her own short text. Her Letters were after all a critique and commentary of Smith. So she appended them to the translation. Although the Letters are in fact a more like a treatise than a record of correspondence (there is in fact only one letter writer involved), each chapter is set out as a letter to someone addressed as C***, announcing the topic of discussion, linking it to the previous one, and at the end, drawing out the conclusions to be taken forward to the next chapter. C*** is also an excuse for considering objections to Grouchy's arguments, with many paragraphs starting with formulas such as "No doubt you will tell me, my Dear C***". So C*** is very much a philosophical interlocutor, the Platonic touchstone to Sophie's Socrates. So who is C***? The obvious assumption is that it is Sophie's husband, Condorcet. But there are reasons why this is probably not true. First, her husband was dead by the time the Letters were prepared for publication. Secondly, if Sophie was to record a fake dialogue with a real person then she would probably have picked someone she actually corresponded with - in 1791, when the letter were written, Sophie and her husband were not apart long enough to correspond. But there were at least two more Cs in Sophie's life, to whom she was very close, with whom she did correspond and who were still alive when the Letters were published. They were her sister Charlotte, and Condorcet's close friend, Pierre George Cabanis. Of the two, C*** cannot be Charlotte, as 'My Dear C***' in French is 'Mon Cher C***' which is masculin. So Cabanis is more likely. Cabanis, as it happens, did correspond with Sophie on topics very close to her Letters, on Physiology, a materialist science aiming to understand human beings through their bodily organs. In 1802, Cabanis published his Rapports du Physique et du Moral de l'Homme, in which he explores the relations between bodies and morality, discussing for instance, the influence of weather and digestion on mood and decision making. Prior to publishing this, he corresponded with Sophie, and had long discussions with her on the subject.

Physiology is also central to the Letters on Sympathy, as Sophy argues that our moral feelings are born out of the physiological response that ties a newborn to the person that nurses her and holds her. Cabanis and Charlotte de Grouchy became lovers during the Revolution, and in 1796, they were married. Some readers like to see a love story behind every text (in particular, texts written by women!) but in this case, we must suppose that C*** was very much an intellectual interest (and a close family friend) but not a love interest. Cabanis was by profession a doctor in medicine but did not practice. Some say that was because of his own poor health. Some say that he was in fact a spy, not a doctor. He is also reputed to have given Condorcet a dose of poison to hide in a ring. And this poison, in some accounts of Condorcet's death, is what he took to kill himself when he was captured in March 1794. Charlotte Corday died at the guillotine in July 1793, a few weeks after Manon Roland’s arrest, and a few days after Olympe’s. Charlotte had come down from her native Vendee, in the north west of France, just below Britanny, to murder Jean-Paul Marat, the ‘friend of the people’ and leader, with Robespierre, of the Terror. She was an aristocrat, who left to her own devices, had ‘read everything’ in her parents’ library. She was a republican, who wanted to save the republic by ridding it of Marat, and not, as the English believed at the time, a royalist. She came to Paris, rang Marat’s door bell, was admitted to his bathroom where he was writing in the tub, to relieve a skin irritation, and she stabbed him. She was arrested immediately and tried very publically. A few days later she died. When we talk about women who were important actors in some historical event or other, very often there is a focus on what they looked like, in particular, whether they were pretty or not. (This, of course, does not simply apply to political women from the past but is still very much in force!) What's interesting about Corday's case, is that descriptions and portraits of her after she was caught are very different from earlier descriptions or portraits. Before the murder, Charlotte Corday was described as pretty, beautiful even, by all who saw her. Even Chabot, the Montagnard who thought her a horrifying accident of nature, and fancied he could detect plainly her criminal propensities painted on her face, still described her as having ‘spirit, grace, superb height and bearing,’ But the death of Marat changed the way she was perceived. Fabre d’Eglantine, actor and Danton’s private secretary, captured this reversal in his ‘Moral and physical portrait’ of Corday for the daily newspaper Le Moniteur Universel. “This woman who has been called very beautiful was not beautiful. […] she was a virago, fleshy and not fresh, without grace, dirty, as are nearly all female philosophers and blue stockings. Her face was covered in red patches, and featureless. Height and Youth are proof indeed! That is all it takes to be beautiful while on trial. Moreover this observation would not be needed if it were not for the general truth that any woman who is beautiful and knows it cares for life and fears death.”  Cities don't stay still. Their shapes change. Rivers move, neighborhoods are destroyed to make way for new roads, and buildings fall down and are replaced with little or no respect for the people that once lived there, or the things they said and did. Paris underwent a great deal of change in the 19th century. In 1853, Napoleon III commissioned his prefect, Haussmann, to redesign Paris so that it would be beautiful, united and airy. The old Paris was dirty and unhealthy - there were too many people living in confined spaces, and a lot of sickness and death. But it was also easier to ferment revolt in dark and narrow streets. In June 1832 and May 1848, the streets of Paris had been the scene of much fighting, with barricades being set up in the narrow passages, piles of furniture and debris, upturned paving stones. This would no longer be possible in Haussman's wide boulevards. Haussman worked on the Rive Droite first. But his most drastic redesign was perhaps the Ile de la Cite, where the Conciergerie, the last prison of those who were executed in the Revolution, stands. Between 1859 and 1867 the Capital was transformed from a nest of narrow breeding disease and discontent, to a network of large, airy boulevards, connected by the remaining truncated streets.

The first boulevard constructed was the Rue de Rivoli, lounging the Seine river on the Rive Droite. This is by far the fasted way from the Conciergerie, on the Ile de la Cite, to the place de la Concorde, previously Place de la Revolution. In other words, had this road existed in 1793, Manon Roland and Olympe de Gouges would have had a much more comfortable journey from their prison to the guillotine. In 1870, Haussman was dismissed. The Parisians had had enough of their city being constantly turned upside down, and his projects were expensive. Nonetheless, they were continued until 1927. And seven years after Haussman's dismissal, the Boulevard St Germain was constructed. Many buildings were taken down in order to make space for this, including the prison where Manon Roland was first taken, L'Abbaye. The space where the prison building once stood is now occupied by a restaurant from a chain specialising in Belgian mussels. Whenever I despair about not having enough time to work on some writing project or other, I think of Manon Roland, and her very strict productivity regime. Those who know how to organize their work always have leisure time. It is those that do nothing that lack the time to do anything. Moreover it is not surprising that women who spend their time in useless visiting and who think they are badly dressed if they have not spent a great deal of time at their mirror, find their days too long through boredom and too short for their duties. But I have seen those we call good housewives become unbearable to the world and even their husbands through a tiresome attention to little things. An Eighteenth-century wife and mother, she says, ought to be well enough organised that she can fulfil her housewifely duties and do something useful with her life, such as write philosophy. She has firm ideas as to what those housewifely duties consist of: I expect a woman to keep her family’s linen and clothing in good order, to feed her children, order, or herself cook dinner, this without talking about it, keeping her mind free and ordering her time so that she is able to talk of something else, and to please, at last, through her mood, as well as the charms of her sex. But all this, she tells the reader of her Memoirs, ought not to take up so much of one's time that it would stop us being productive writers. She herself, even at her busiest, never spent more than two hours a day doing housework.

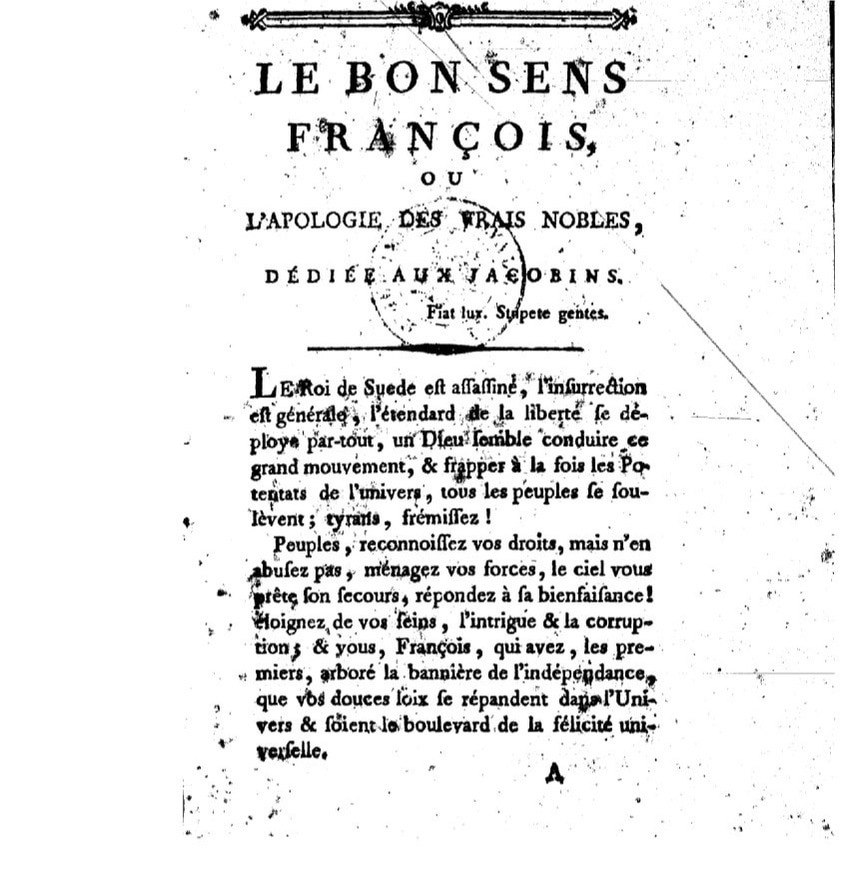

Olympe de Gouges was in the habit of relating personal anecdotes at then end of her published texts. So for instance, the story of how she travelled from Auteuil to Paris, and the evidence that she corrected her own proofs is printed at the end of the Declaration des Droits de la Femme. In a 1791 text entitled "Le Bon Sens François" she tells an amusing story about what happened when she overheard two men in a coach talking about the famous author Olympe de Gouges. She interrupted the conversation: -"So you know her quite well?" - "Certainly. Her husband was a cook: she refuses to bear his name! No one knows who her father is. As to her works, not one word comes from her. She cannot read, they were written for her, affecting carelessness and ignorance in the style to make it seem that they are hers." - "But I have seen her draft a piece in front of several witnesses, and she even won a bet by doing so." Replied Olympe. - "Ah! Madam! The play was written for her in advance and she was made to learn by heart." - "Are you quite sure?" - "So sure that I am prepared to bet she could not do the same again in front of me. Besides I know what I am talking about - I am one of her fortunate admirers." Olympe gave her final reply as she was leaving the car: - "Sir, I have listened to your idiotic claims with the calm of a philosopher, the courage of a man and the eye of an observer. I am this same Olympe de Gouges that you never did know and never could. Take advantage of the lesson I am giving you: men like you are common enough, but women like me are the work of several centuries." [Dialogue adapted and translated from Olivier Blanc, Olympe de Gouges, p. 76.] In 1788, when Olympe de Gouges printed the first volume of her Works, she included a play titled Le Mariage Inattendu de Cherubin. This play had been written in homage to Beaumarchais's Marriage of Figaro, and Olympe was hoping to attract the great author's interest or patronage. Unfortunately all she attracted was his ire. Beaumarchais decided, without having read it, that her play plagiarized his and he instructed the actors of the French theatre, with whom he has a great influence, not to take it. Undeterred, Olympe decided that she would make the best of things and seek actual feedback from Beaumarchais on her work. She wrote him a note, and like Manon Roland with Rousseau, she went to knock at his door, hoping for an interview. The note she handed at the door said:

I come to you as the oppressed come to Voltaire's. I am at your door, and I flatter myself that you will do me the honor to see me.' Beaumarchais' servant took the note to his master and came back with the response that Beaumarchais was busy and could not see her right now. Olympe asked for his at home day, so that she could come back when he was not busy, but was told that Beaumarchais could not be certain of when he would be free. Olympe left in a huff. Four months later, she published her account of the incident in the preface of the play. Unlike Manon Roland, she lacked the delicacy to make light of the incident. Le Mariage Inattendu de Cherubin remained unperformed, until she decided, later on, to take it and others (her reputation with the Theatre Français never quite recovered from Beaumarchais' assault) to the provincial theatres. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed