|

Louisa May Alcott's novel, Work: a Story of Experience, is a defence of women's quest for independence through work that seems to owe much to Mary Wollstonecraft's philosophy. One running theme of the novel is that poor women can achieve emancipation through work. Much work doesn't allow them to do so because it is drudgery for abusive employers. But the book features a number of virtuous people who make it part of their life work to help create better employment situations for women in need, women who want to escape forced marriage (as is the case with 15 year old Kitty) or women who forfeited family ties by entering in a relationship outside marriage and are now shunned by society (such as Rachel) The heroine of the novel, Christie Devon, declares to her aunt in the first line of the book that there is going to be 'a new declaration of independence', and that she is going to leave home, try out various lines of work and hopefully end up with a career. She wants to see the world and earn a living, but mostly, she wants to be free ('I do love luxury but I love independence more', says she when turning down a rich suitor she does not love). She tries various professions: maid, governess, actress, companion, seamstress, and at one point she is without work and destitute and considers suicide, but is rescued by a woman who is part of circle of people who help working women. By the end of the story, Christie has found a career: she has become a speaker and activist on behalf of working women. The women she helps are poor, but she believes that there is room for improvement in the condition of rich women too, and when a rich acquaintance comes to ask her how she might help, she tells her as much: rich women 'need help quite as much as the paupers, though in a very different way'. The task she gives Bella is to set up a beautiful and elegant salon in her brother's home, and there set a new fashion, one for common sense. She adds: " I don't ask you to be a De Stael and have a brilliant salon: I only want you to provide employment and pleasure for others like yourself who are now dying of frivolity or ennui." What's distinctive about Alcott's proposal is that the salon is designed primarily for the improvement of women. Like a traditional salon, it is hosted by a woman, and welcomes men and women of good society. But unlike traditional salons which are mostly for facilitating the exchange of ideas, literary, political or otherwise among men, this one is designed to encourage women to think about things other than dress and parties, and to embrace more 'old-fashioned' and 'commonsensical' ideals. This, according to Alcott is the sort of help rich women need, and it sounds very much like Wollstonecraft's quest for a slowly achieved revolution in manners.

0 Comments

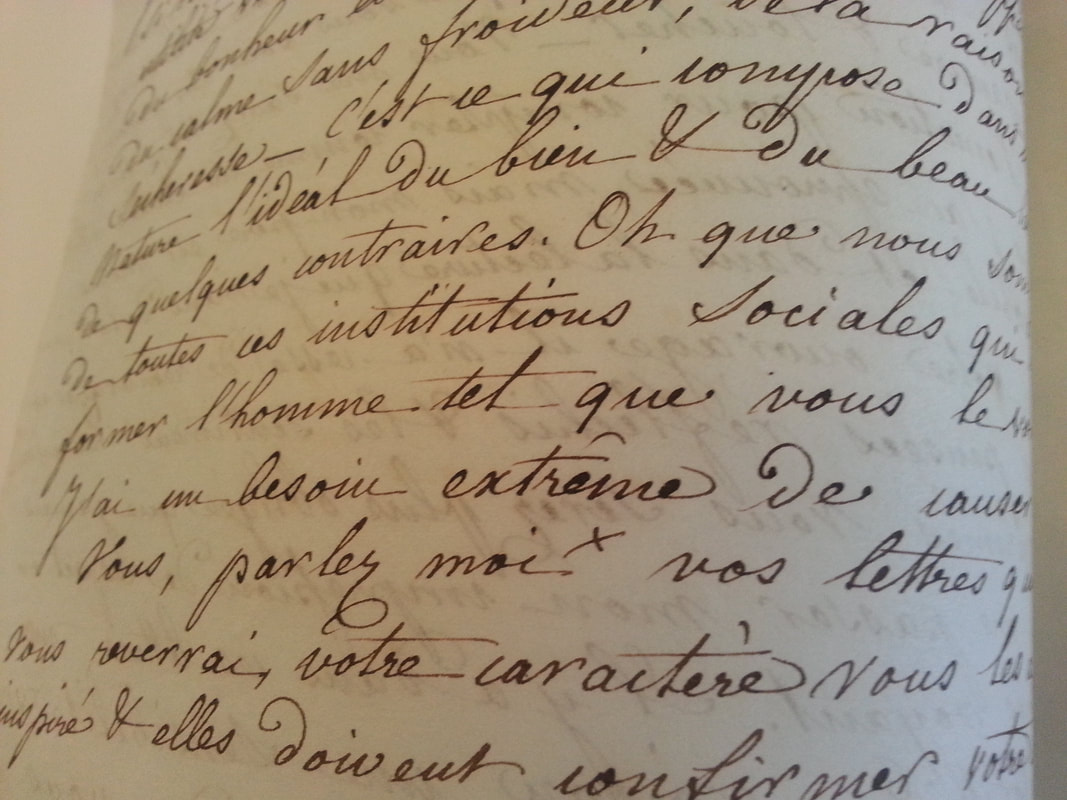

I was alerted by Eveline Groot, who gave a great talk this week at the Braga Colloquium on Women and the Canon, to yet another slight in the history of philosophy against a woman. This time, it's against Germaine de Stael, a writer who saw her share of slights in her life time, including some from Manon Roland and Sophie de Grouchy. But what Eveline Groot found is a 20th century historian of philosophy (or philology), who chooses to minimize the impact and import of Stael's philosophical commentary on Rousseau. Writing in 1915 in Modern Philology (13:7), G.A. Underwood claims that in her reading of Rousseau, Madame de Stael saw only the sentimentalist of the New Heloise, and not the rationalist of the On Social Contract, and that her Notice sur le Caractere et les Ecrits de J.J. Rousseau demonstrate 'little beyond an enthusiasm for Rousseau's ideas' (adding that the enthusiasm itself was significant'. Underwood concludes the introduction to his paper on Stael's interpretation of Rousseau by announcing that: 'The thesis will be that Rousseau leads Madame de Stael to become absorbed in her feelings'. The conclusion of the paper reads as follows: Such is the somewhat undeveloped Rousseauism of Madame de Stael when she began writing. It is an emphasis on temperamental inclination rather than a ripened criticism. A continuation of this study would show how in her mature and original work Madame de Stael gradually thought out to definite literary and philosophical tenets those ideas of Rousseau to which she was so strongly attracted. So one may well wonder why Underwood decided to write the article showing that in her early work, Stael was not a proper philosopher, but yet another female with inflamed emotions, rather than study the philosophical tenets he agrees she later came up with.

We can add G.A. Underwood to the list of scholars for whom, when it comes to the study of women philosophers, the important work to be done is to show how uninteresting and un-philosophical their work was. Although Madame de Stael is well known, as a historical figure and a writer, she remains very much in the background of the research I have conducted so far on the women of the French Revolution. I mentioned Roland's quip about her salon in my last post. This is as close as the two women got. Stael and Gouges never met, and although she and Grouchy moved in similar aristocratic and international circles, they were certainly not friends. Germaine de Stael was the daughter of Jacques Necker, a Swiss banker appointed by Louis XVI as finance minister in 1777. Necker held this post until 1781, when he was dismissed for having hidden the debts of France in his reports. He was recalled briefly in 1788, but dismissed again on 12 July 1789. Camilles Desmoulins, in the famous speech rousing the French people to revolt, invoked the King's treacherous treatment of Necker. Necker comes across as something of a quiet hero of the revolution, a man who did his best to resist the decadence of the French regime and serve the people. This is certainly how his daughter saw him. However, to see him as such we must leave out the story of how he became minister in the first instance. In 1776, Turgot was minister of finances, and Condorcet, director of the mint, his right hand. This was a difficult period for the French economy, marred by the flour wars, the rising price of grain which resulted in famines, and the ensuing revolts. Turgot attempted to deal with the crisis by getting rid of a number of regulations (including pricing) which had a throttling effect on the production of bread. But before he could succeed (or fail) he was dismissed and replaced by Necker. People in Turgot and Condorcet's circle believed that Necker had had a hand in his dismissal, privately misrepresenting to the King what Turgot was doing. Condorcet, when Turgot was dismissed, did not want to continue in his position. But the King ordered him to stay. This background of political squabbling may explain why Grouchy and Stael never became friends. Each was loyal to her husband or father. The rift grew bigger when the Condorcet's close friend and ally, Mirabeau took over from Necker in the heart of the French people. Necker left France, and after 1789, had no role to play in revolution. Stael fled Paris in 1792, after the September massacres, and took her salon to her chateau in Switzerland. When Napoleon came into power, he took an instant dislike to her, and she had to exile herself again. As powerful figures in French literary circles, however, Stael and Grouchy could not ignore each other. And when Grouchy's Letters on Sympathy came out in 1798, Stael wrote to her, admitting that she envied both her style and the depth of her analysis. It is not clear whether Sophie de Grouchy took the homage seriously.

Wilhelm von Humboldt, who visited Sophie in 1799 reported the letter in his Journal Parisien. "She showed me a letter which Madame de Stael had written about her book to which she gave exaggerated praise" |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed