|

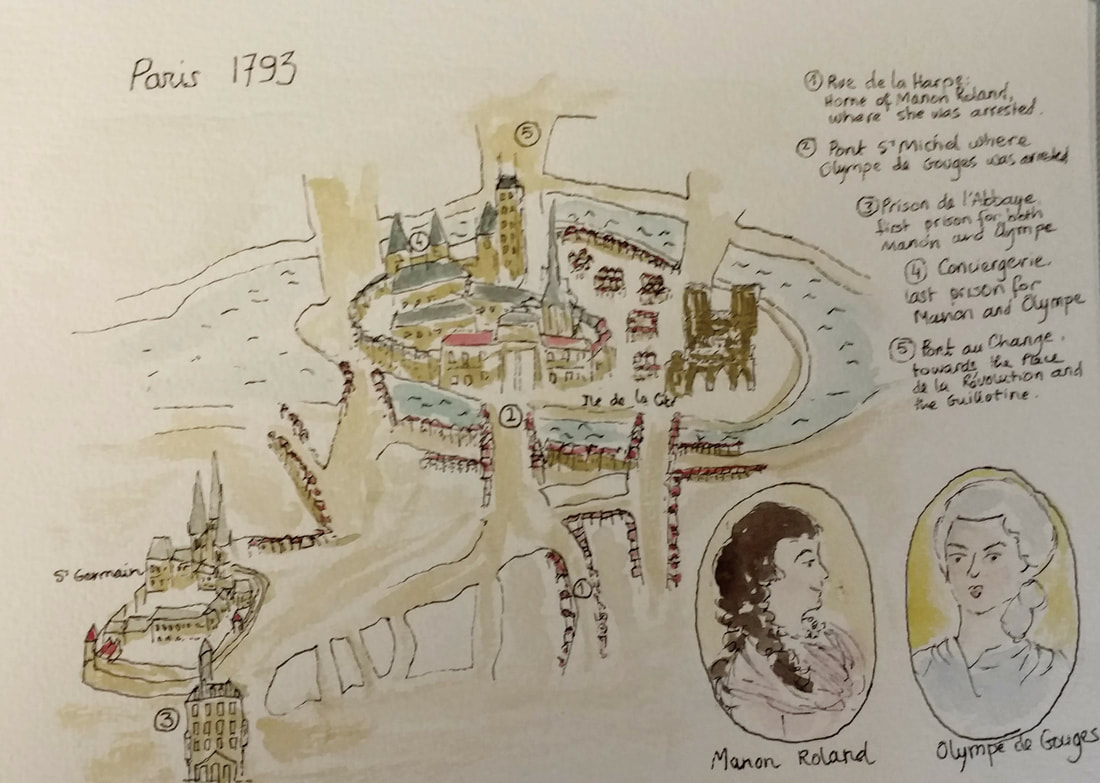

Just under two years ago, I took a walk around Paris with my daughter and her friend, trying to retrace the final steps of Olympe, Manon and Sophie in 1793. Olympe and Manon's ended at the Guillotine, while Sophie took long walks from Auteuil to Paris, to visit her husband in hiding and make a living as a painter. As the map I drew then shows, their paths didn't cross that much then - they had before, in Paris clubs and salons, and at Madame Helvetius's home in Auteuil.

So I thought to look at the paths they took separately and below is a map of Olympe and Manon's final steps. It takes them from the places they were arrested: at home for Manon, and on the Pont St Michel for Olympe, to the first prison they shared (though not at the same time), l'Abbaye, which was just below the Saint Germain des Pres monastery (both prison and monastery are now gone); to the Conciergerie where both spent their final nights, and last, the Pont au Change, where the cart driving them to the guillotine took its first turn.

1 Comment

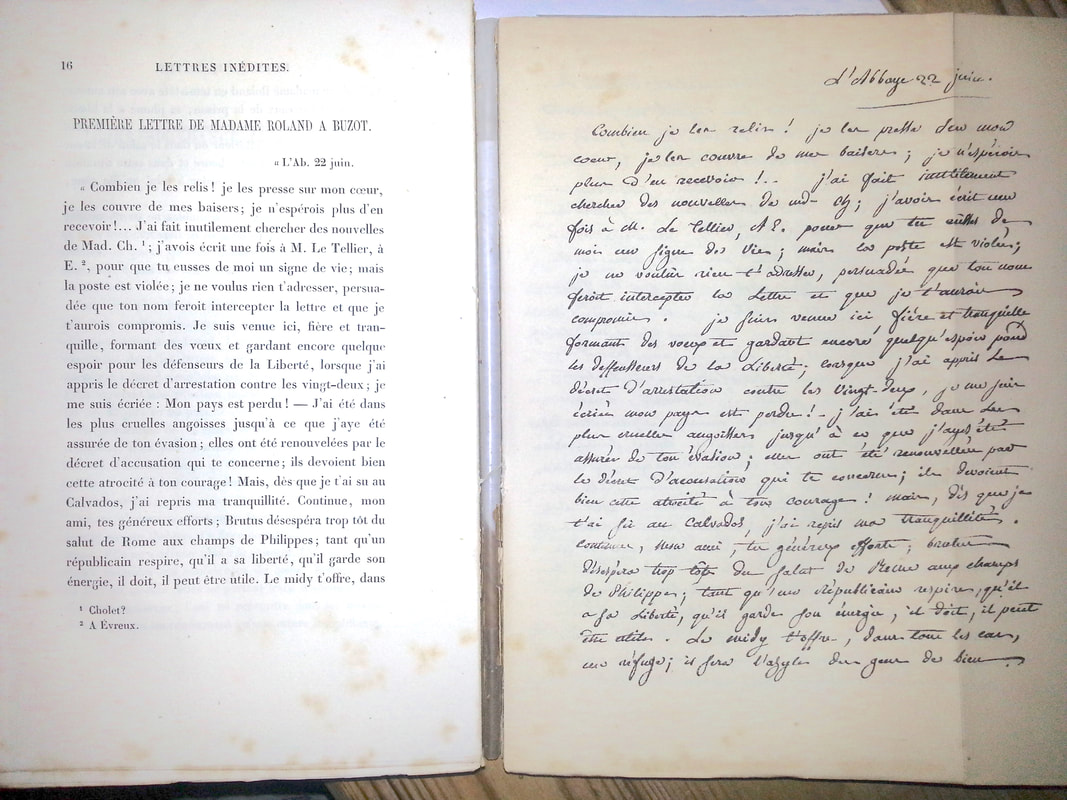

During her trial, and throughout her Memoirs, Manon Roland presented herself as a model wife to her husband. But reading through her recollections of the early days of hers and J.-M. Roland’s courtship, one is underwhelmed. Their courtship was long, their engagement business like – he was always hesitant and there is very little passion showing in Manon’s accounts. It was not a marriage of convenience: Jean-Marie Roland saw his wife as an equal in all respects, he did not attempt to dominate or curtail her, and they were partners in all their projects (except for the Memoirs which she wrote while she was in prison and he in hiding). There was a strong friendship between the two but perhaps not much more. Towards the end of her life, however, Manon did fall in love with a young Girondin (he was six years younger than her, while her husband was twenty years her senior), François Buzot. François was also married, and neither he nor Manon had any intention of breaking down their marriage. Nonetheless, Manon told Jean-Marie that she no longer loved him, and that she loved François. This is perhaps why, in the weeks before her arrest, she had planned to leave Paris. She needed some space to think. Manon's correspondence with Buzot was hidden from the public when the letters were first published, so that the image of her as a virtuous wife remained. But the truth came out in the 19thcentury: after all, all interested parties were dead. Below is a letter Manon wrote to Buzot shortly after she was imprisoned, and after the decree for the arrest of the Girondins had been issued. She had heard that Buzot, together with Jérome Pétion (whose wife was Manon 's neighbour at Sainte Pélagie, had managed to escape and that they were in the South-West of France, near Bordeaux. This is a love letter: she tells him how she covers his letters to her with kisses. But it is also a political letter: one that shows both hope and despair. She tells him that when she heard of the arrest of twenty-two Girondins, she thought France was lost. But then, she asks him to stay alive, because a republican ‘while he breathes, while he has his freedom, can and must be useful’. A few weeks after Manon’s death at the Guillotine, Buzot and Petion shot themselves in the woods of Saint Emilion. Their bodies were discovered later, eaten by wolves. While researching the links between Cabanis’s posthumous work, his Letter to Fauriel on First Causes, and Sophie de Grouchy’s Letters on Sympathy, I noticed how difficult it was to find any reference to Sophie. I had good reasons to look for these references. Cabanis and Grouchy collaborated during most of their adult lives. They were both members of Madame Helvetius’s salon at Auteuil, and then Cabanis helped populate Sophie’s own salon after Condorcet’s death. They met in 1786 when Grouchy married Condorcet. They were neighbours in Auteuil between 1795 and 1802, and then again near Meulan from 1807 to 1808 when Cabanis died, aged 51. They were also related – Cabanis and Grouchy's sister Charlotte were lovers from 1791 onwards and married in 1796, after the birth of their second daughter. When Sophie wrote her Letters on Sympathy, the C*** she addressed the letters to was not Condorcet, but Cabanis, with whom she shared an interest in physiology. Claude Fauriel came into the scene in 1801, first a member of Sophie’s salon (he was recommended by Madame de Stael about whose works he had just written an essay) and then Sophie’s lover. Fauriel was ten years younger than Sophie and fifteen years younger than Cabanis. Fauriel was a historian of literature, but shortly after coming into contact with Sophie and her circle, he turned to philosophy, and started working on a history of Stoicism. The manuscript for this was lost, in 1814, and nothing came of it. At the time Cabanis wrote his Letter to Fauriel, it would have been just in its beginnings. The Letter to Fauriel is about Stoicism – what they got right, what they got wrong. Cabanis is defending a vitalist thesis derived from the Stoic view that divine reason permeates the universe. And he commands the Stoic moral view that to live well is to do as much good to others as one can. But he objects to one interpretation of Stoicism which says that pain is not an evil. If it were not, then we would have no reason to want help those in pain.

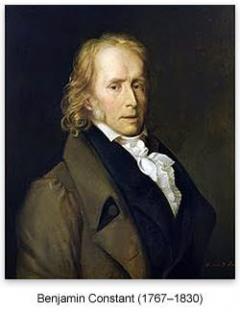

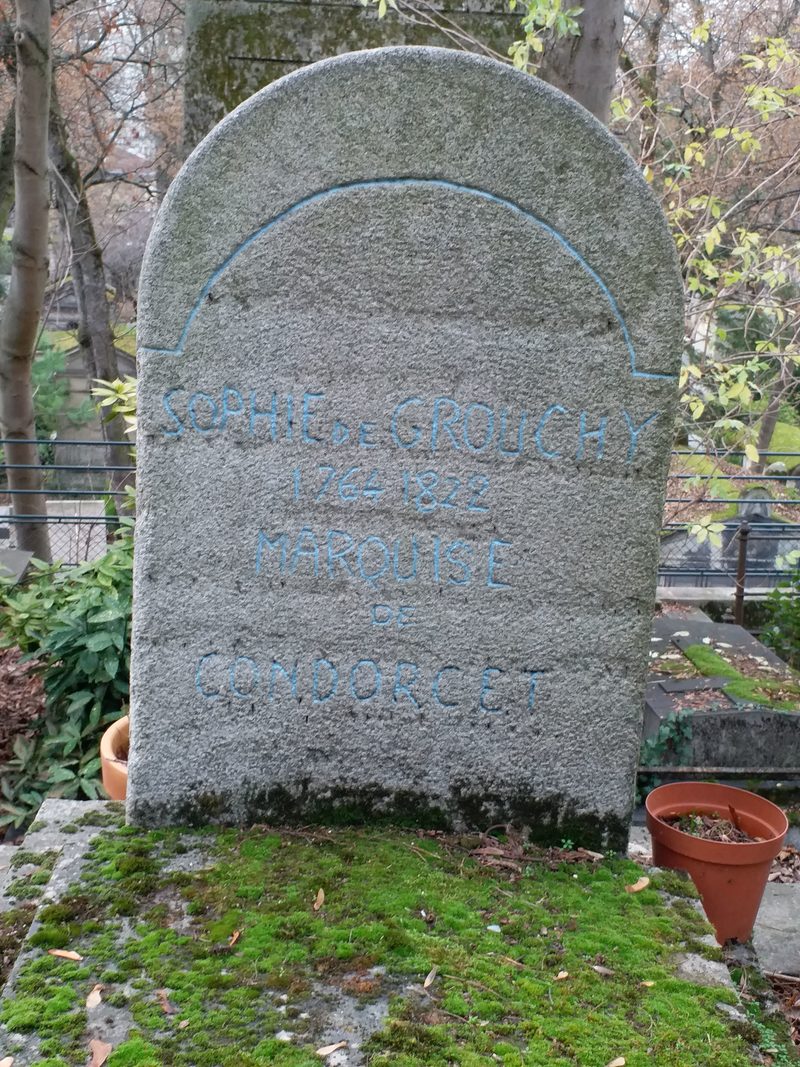

The focus on pain and morality, on the role of reason in the development of sympathy for all (a moral and political cosmopolitanism) is highly reminiscent of the Letters on Sympathy published by Sophie in 1798. Fauriel’s interest no doubt prompted Cabanis’s Letter, but its contents are more of a continuation of a dialogue with Grouchy than they are with her young lover. One remark, in particular, makes the link clear. “No one knows better than you” he tells Fauriel, how important the study of religious beliefs is to history. Cabanis then goes on to describe something very like Condorcet’s Sketch of Human Progress, the philosopher’s last work, and one that had been edited, and even perhaps written in collaboration with Sophie de Grouchy. Of course none of this can be found in commentaries on Cabanis or Fauriel. Sophie de Grouchy’s very real, very substantial influence is made to disappear or is made out to be nothing more than the hosting of a salon in which brilliant men could develop their ideas. And she is not the only woman author to have been wiped out of this particular bit of the history of philosophy. Benjamin Constant is cited by several commentators (Sainte-Beuve, and Guillois in the later 19thcentury) as having been influential in a debate between Fauriel and Cabanis. However, his own partner, Germaine de Stael is not cited, even though it is was because he had been writing an essay about her work that Fauriel was introduced to Grouchy’s circle. In January 1793, six months before her arrest, Manon Roland wrote the following letter to her friend Johann Kasper Lavater in Zurich. She had first met Lavater in France, and then during her visit to Switzerland with her husband in the 1780s. She was, like many of her contemporaries, impressed with his science of physiognomy, using a person's facial features to make deductions about their character. Lavater used his science to draw conclusions about criminology, and this is perhaps the source of the advice he sent Roland via the intermediary of his wife. Manon's letter to Lavater gives a vivid impression of what life at the onset of the Terror must have been like for those who did not sympathize with the Commune: constant fear, and the conviction that one must continue to defend liberty, at any cost. January 1793 to Lavater, in Zurich Today I went for my third Paris walk, following the steps of Olympe, Manon, and Sophie. The first at taken me to their homes, prisons, and place of execution. The second to the Conciergerie, where Manon and Olympe spent their final days before being taken to the Guillotine. Today was about final resting places. In Sophie's case, it was fairly straightforward. Together with my mother, children, my sister, her boyfriend and my niece and nephew, we walked through the Pere Lachaise. My daughter and nephew who'd distinguished themselves in our investigations of the missing hospital of the Conciergerie found Area 10, where the grave was. But it was my sister who saw the grave first. It stood out, luridly, because someone had gone over the simple engraving of her name (she'd wanted a cheap burial) with light blue chalk. Visiting the bones of Olympe and Manon had to be just that: going to see their bones, or at least, a bunch of bones that probably included theirs. Because they were first buried in a common grave, then moved to another common grave, then removed to the Paris Catacombs, it is not clear that there bones are where the sign says they might be, Nonetheless, we walked down the 230 steps to the catacombs, and then 1,5 kilometers in the underground corridors built under Louis XVI and the Medieval quarries to the galleries where the bones of dead parisians are artfully arranged. There are plaques indicating which graveyard was emptied where, and the section I was looking for was that of the old Madeleine cemetery. A friend's mother, whose job it is to identify bones, tells me that it might be possible, in principle, to reassemble the skeletons in this area, and figure out which were women, which had been decapitated, and which had born children. This would be a way to narrow down the number of bones possibly belonging to Manon and Olympe. As it is, they are mixed up with Brissot and the 21, decapitated in a fateful half hour in late October 93, and those of everyone else who lost their heads between 1792 and 1793 (except for Louis and Marie-Antoinette, whose bodies were taken elsewhere by their brother, Louis XVIII).

I did, however, like the look of a line of skulls, down on the left hand side of the stone pillar bearing the sign. I thought they might well be the heads of Olympe, Manon, perhaps Brissot and a few others who died at the Guillotine in the Autumn 93, carrying on their conversations, and perhaps wondering what on earth the world was coming to. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed