|

When Manon Roland was 21 she heard that Rousseau was in Paris and decided to try and meet him. A friend of hers, a fellow Genevese provided the introduction and the reason for the visit: he's commissioned some music from Rousseau and she was to pick it up. So she wrote him a letter and went to his house, accompanied by her nanny. She relates the visit in a letter to her friend Sophie, on 29 February 1776. Thérèse Levasseur with Jean-Jacques Rousseau. When Manon knocked, the door was open by Therese Levasseur who asked her rudely what she wanted.

- "To speak to Monsieur Rousseau - is this his home?" - "What do you want with him?" - "An answer to a letter I wrote a few days ago." - "Well, Miss, you can't speak to him. But you can go and tell the people who made you write - for surely you did not write this letter..." - "Pardon me?" - "The hand itself is clearly a man's." - "Would you like to watch me write?" Laughed Manon. She did not see Rousseau, who was old and sick and saw no visitors anyway, but Manon went back home with, she says, the slight satisfaction that he found her letter well enough written that he thought it could not be by a woman.

0 Comments

Janet Todd, Wollstonecraft's biographer, suggests that Wollstonecraft may have been contacted in 1792 by Condorcet and Paine to help rework the plan for educational reform that Talleyrand had started in 1791. Might Wollstonecraft have at least considered taking them up on the offer, and might she have met Condorcet's wife, Sophie de Grouchy over dinner? Probably not. When Wollstonecraft was in Paris, she mostly visited English nationals, such as Helen Maria Williams, and Johnson's associate, Thomas Christie. She was close, ideologically, to the Girondins, some of which were fluent English speakers. Brissot, for instance, had visited England, and developed a friendship there with Catharine Macaulay. Manon Roland also spoke English, having taught herself at the beginning of her marriage, and travelled to England, where she was much impressed with the cleanliness and simple habits of the inhabitants. Sophie de Grouchy was also a fluent English speaker and writer, so that her salon in the early years of the revolution attracted foreign luminaries such as Thomas Paine and Jefferson. But by the time Wollstonecraft moved to Paris, Sophie no longer had a salon, and Manon did not admit any woman in hers. It is therefore unlikely that they would have met. Had they read Wollstonecraft? Again there is no evidence. But a letter dated 20 August 1791 from Sophie to her friend Dumont suggests that perhaps she may have come across one of Wollstonecraft's books. Sophie thanks Dumont for sending her books and political news from England and says: "Until I receive more news from you, I will be busy reading the book you sent me and dreaming about the best way to raise reasonable women who can live with men who are not and will not be reasonable towards women for a long time from now". This could, of course, be coincidence. But it does suggest that the book Dumont sent her and Sophie's dreams might be related. And who, better than Wollstonecraft could be the inspiration for such dreams?

Charles-Geneviève-Louis-Auguste-André-Timothée d'Éon de Beaumont 1728 – 1810, known boht as Chevalier d'Eon and Mademoiselle d'Eon was a soldier and spy who immigrated to England in 1763 and lived life as a woman from 1777 until their death. In London, D'Eon was famous for winning duels dressed as a woman (and made money from betting). Mademoiselle d'Eon was held as a model by several women authors, including Mary Wollstonecraft and Olympe de Gouges. Wollstonecraft: "I shall not lay any great stress upon the example of a few women (Sappho, Eloisa, Mrs. Macaulay, the Empress of Russia, Madame d'Eon, etc. These, and many more, may be reckoned exceptions; and, are not all heroes, as well as heroines, exceptions to general rules? I wish to see women neither heroines nor brutes; but reasonable creatures.) who, from having received a masculine education, have acquired courage and resolution;" (A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. 1792. Chapter 4.) Gouges: "No doubt you will doubt my valour; Mademoiselle Déon [sic] proves only too well that my sex is not lacking in courage. I will admit there are few with this martial character, but there have been some. And you who are more fearful than women, do you not fear this sex that has distinguished itself in other circumstances, and may I, myself, convince you that Mademoiselle Déon has transmitted to me her intrepidity? Would you refuse me the pleasure of blowing out my brains with you?" (Le Bonheur Primitif, 1789, Translation Clarissa Palmer). It's not clear whether Wollstonecraft or Gouges had any arrested views as to D'Eon's gender - D'Eon was famous both as a man and a woman. But both felt that, as a woman, she was someone to aspire to. There is in fact, surprisingly little discussion of D'Eon's gender - the switch from living as a man to living as a woman seems to have been generally well accepted by all. But when D'Eon died, doctors did feel the need to examine their body to verify gender - this was inconclusive.

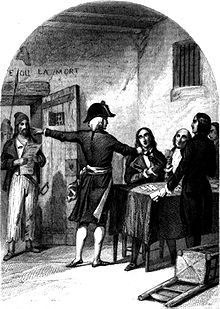

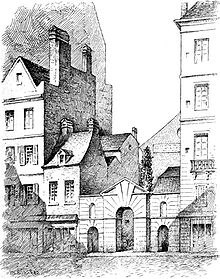

D'Eon was buried in St Pancras. When the graveyard was dug up to make space for the railway in 1877, D'Eon, along with other famous corpses, was listed on the Burdett-Coutts memorial (pictured above) - as "Chevalier d'Eon". The prison de l'Abbaye was a 16th century prison, which was taken down in 1854 to make space for the Boulevard St Germain, On 1 June 1793, Manon Roland was arrested at her home on the Rue de la Harpe, a building which stood where number 35 now is. She was taken to l'Abbaye, on the corner of St Germain des Pres. In June 93, there were only eighty prisonners left in l’Abbaye. A few months earlier, before the September massacres, it had contained over 400. That is not to say that the prison was deserted when Manon first arrived, as one of her first sight, when she was brought in, was of five men lying on camp beds next to one another. The prison wardess apologised that she was not expecting her, and so has no room for her yet. But she found her a sitting room. There Manon set up a writing table, and her maid brought her Plutarch’s Lives, her favourite book since childhood, and Hume’s History. She’d have preferred Catharine Macaulay’s History of England, a republican text she had started reading the first few volumes in English, and that she greatly admired. But it was Brissot who had lent them to her, and an edict had been made for his arrest, along with twenty-one other Girondins, so Madame Roland surmised that he was probably not home. A week later, more prisonners arrived and she was moved to a smaller room – her sitting room could take more than one bed. Again, she set up a place to write, and in the little cell, which she kept as clean as she could, she recalled her childhood spent writing in her bedroom. Healthy and comfortable, and only worried for the sake of others – she read and wrote. Twenty-four days after she was arrested, she was set free again. She was almost reluctant to leave her peaceful cell, and only later did she learn that its occupants after her were her friend, Brissot, and then the famous Charlotte Corday. And on 20 July, Olympe de Gouges was brought to the Abbaye. As soon as Manon reached her front door, however, she was arrested again, and taken this time the the Pelagie Prison. She only left Pelagie to go the Conciergerie, the last prison of those who were condemned to the guillotine. I went to look at the Prison de l'Abbaye, or at least the space where it once stood. Rather incongruously, it is now a restaurant serving mussels and chips.

Just as Olympe de Gouges did, Sophie de Grouchy had to relocate to the suburbs during the Terror. In 1793, the Jacobin Chabot had issued an order to arrest her husband, Condorcet. Condorcet had gone into hiding in the house of Madame Vernet, on the Rue des Fossoyeurs (now the Rue Servandoni). Their property was confiscated by the government, and Sophie, together with her young daughter, her nanny and her sister Charlotte, moved to a house on the Grande Rue D'Auteuil, not far from where Madame Helvetius lived. Several times a week, Sophie walked into Paris to visit her husband. As she did not want to be recognised, or to attract anybody's attention to Condorcet's hiding place, she came dressed as a peasant woman, pretending to be with the crowds of farmers come to sell their goods to the starving capital. Once through the gates, she would lose herself in the crowds come to see that day's executions at the Place de la Revolution (now Place de la Concorde), then cross the river to reach the left bank, and walked towards the church of St Sulpice, and beyond that to the street where her husband was hiding. Often she would bring him books, or notes that he needed for his work - as he'd had to leave home in a hurry. She would also stay and encourage him, and work with him. His last work, the Sketch of human progress, was almost certainly something they worked on together. After seeing her husband, Sophie would walk back across the Seine towards the Rue St Honoré, where she rented an underwear shop and the half-floor above it. Putting Auguste Cardot, younger brother of her husband's secretary, in charge of the shop, she set up a studio in the alcove and worked on her miniatures from there. Thus she insured that she had sufficient income to see to the needs of her husband, her family and herself until she could claim back some of what the government had seized.

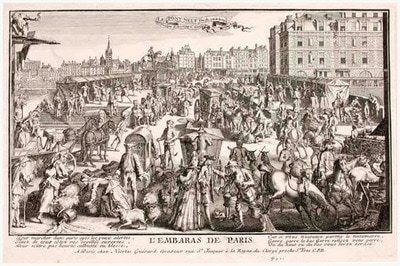

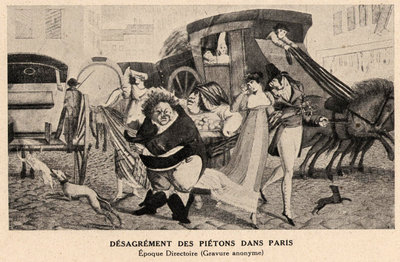

By the time the Terror kicked in, living in Paris was no longer a safe option for those who'd been at all involved with the opposition party and many retired to the nearby countryside. One very popular place was Auteuil, where Madame Helvetius ran her famous salon where philosophers, mathematicians, poets and politicians gathered. Both Sophie de Grouchy Olympe de Gouges moved there. But of course one still had business in Paris. Olympe had to travel there to visit her printer, and make sure her latest tracts were pasted and distributed where she wanted them to be. This meant first getting to Paris, and then through the busy streets to her printer's in the 6th arrondissement. This is Olympe's own description of one particular trip to Paris from Auteuil:

I live in the countryside. I left Auteuil this morning at eight and winded my way to the road that goes from Paris to Versailles where one can often find those famous roadside cafés that inexpensively gather passers by. No doubt an unlucky star was pursuing me that morning. I reached the gate and I could not even find the sad, privileged, hackney coach. I rested on the steps of that insolent edifice that secreted clerks. Nine o’clock chimed and I continued on my way; I spotted a coach, took my place, and arrived at a quarter past nine, according to two different watches, at the Pont-Royal. I took the hackney coach and flew to my printer, rue Christine, for I could only go so early in the morning: when I am proofreading there is always something to do, if the pages are not too tight or too full. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed