|

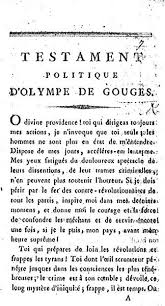

Olympe was arrested on 20 July 1793. Three weeks before that, she was moving her furniture from Paris to a small house she had bought in the countryside near Tours, and where she was about to retire. She had been away visiting properties and spending time with her son, but had come back to Paris to see to the removal of her things. Olympe knew that by being in Paris, and publishing more political tracts, she was putting herself at risk. But the decree against the Gironde had just been issued and she felt she had to do something. Her Political Testament, written at time, reflects her anger and uneasiness: If, in a final effort, I can still save the republic, (chose publique), I desire that even while they immolate me to their fury, my sacrificers still envy my fate. And if one day, posterity notices women, perhaps the memory of my name will be of value. I have planned everything. I know that my death is unavoidable, but how beautiful and glorious it is, for a well-born soul, when ignominious death threatens all good citizens, still to give one's life for our dying country! Her next tract, The Three Urns, is an attack on the Paris Commune. It is printed by her imprimeur, Longuet, on 15 July. He draws 1000 copies. She sends a copy to the committee of public safety, and one to Herault de Seychelle, then she waits a few days - no reply, which she takes to mean that she can go ahead. Her distributer, or afficheur, is a Citizen Meunier who lives in the Rue de la Huchette. On 20 July, Olympe leaves her apartment on the Ile de la Cite, crosses the bridge St Michel, and turns left into the Rue de la Huchette. The Pont St Michel and the Rue de la Huchette are still there. The actual Pont St Michel dates from the mid-nineteenth century. Earlier photographs show a similar looking bridge, with four arches, rather than two, and less flat. And back in the eighteenth century, it would still have had the more traditional aspect of the Medieval bridge, it would have been covered in wooden shops and houses. The members of the Commune are reputed to have met in a tavern on the Rue de la Huchette. If true, this may well have influenced Meunier's decision not to post Olympe's Three Urns. What he actually told her, on the morning of her arrest, is that he was worried that it would rain. One imagines Olympe looking up at the clear sky, puzzled, before she set out to find another distributor on the Pont St Michel. But when she got there, Meunier's daugher, who had followed her pointed her out to three policemen and members of the national guard, She was arrested her and taken to the Depot prison of the Mairie.

0 Comments

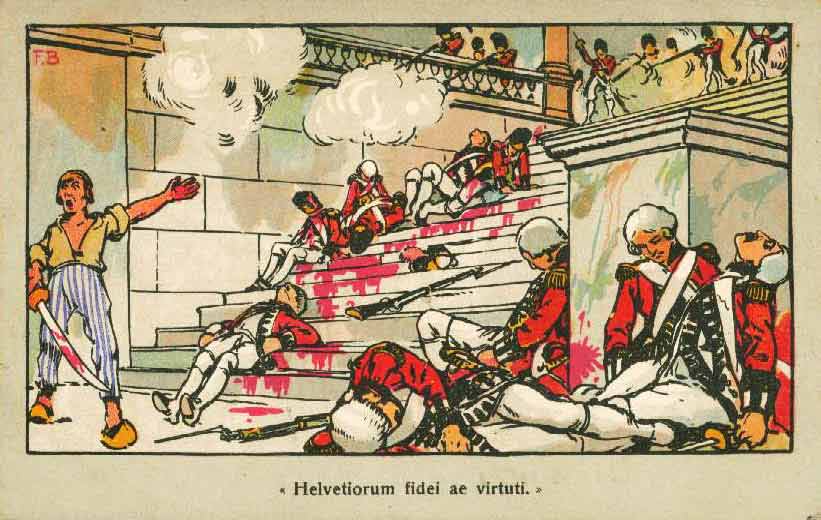

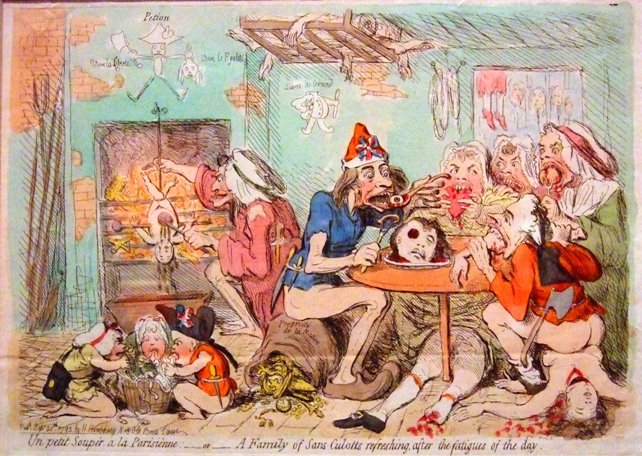

On the afternoon of 2 September 1792, the Tocsin was rung, and and canon was shot as an alarm. Word was out that France had lost Verdun, and the traitors to the republic were blamed - they must have spread intelligence. Who were the traitors? Mostly two kinds: the aristocrats, and the priests who had refused to pledge allegiance to the new civic religion, known as the refractory priests. But most of those were in prison. Manon reports the following anecdote: her husband was then minister of the interior, and one of his deputies came to alert the Paris Commune that some of the prisoners might be at risk. Danton replied testily: "I don't give a fuck for the prisoners or what happens to them!" (Portrait de Danton). There was indeed cause for worry: the last time the tocsin was rung and the canon shot was the 10 August, when the Parisians stormed the Tuileries, where the King and his family was held, and massacred the Swiss guards who were there for their protection. The King and Queen were now at the Temple prison, and quite safe for the time being. But the Swiss guards that survived, and some of the nobles of their entourage, such as the Princess of Lamballe, were in the Paris prisons. By the evening of 5 September, most of them were dead. The British Caricaturist James Gilray published the following picture of a sans-culotte (here depicted literally without trousers!) family eating the flesh of their victims after a day of murders. Unfortunately the caricature was not as far from the truth as it might have been, as Manon reports to a friend a few days later. "If you knew the horrible details of these expeditions! Women are brutally raped, before these tigers tear them apart, entrails are worn as ribbons, human flesh eaten, still bleeding! You know my enthusiasm for the Revolution, well, I am ashamed of it. It has been stained by scelerats, it has become ugly!|"| (letter to Bancal, 9 September 1792)." This episode marked a turn in the Revolution. Those who had been critical of the Commune, or Robespierre, Danton, and Marat - "My friend Danton leads all, Robespierre is his dummy, Marat holds his torch and his knife." - were now reluctant to have anything to do with them. By January, Roland had handed in his demission from the ministry, on 1 June, his wife was arrested, and on 2 June a decree for the arrest of the Girondins was issued. By November, all were dead. "The whole of Paris let it happen... the whole of Paris is damned in my eyes, and I no longer hope that liberty may take root amongst such cowards, insensible to the worst outrages inflicted on nature and humanity, cold spectators of attacks that could easily have been prevented by fifty armed men." (Memoires) There are a number of versions of Manon Roland's Memoires, each presented and edited differently by different editors. Manon gave her manuscripts to friends as she wrote them. Some friends, such as Champagneux, kept them religiously, Helen Maria Williams burned a copy of the Notices Historiques when she found out she would be arrested, and Bosc kept what he was given, but did not hand everything to the editors, seeking to protect his friend's reputation. One thing that is missing from the early editions, based on the Bosc manuscripts, is the story of what preceded Manon's childhood religiosity, and her desire to be sent to a convent. In one early edition, we are told that Manon was simply seduced by religion, and told her mother one day that she wanted to go to a convent to be closer to god. But later editions, restoring the passages kept back by Bosc, tell a very different story. When she was 10, a young apprentice of her father's grabbed her hand and placed it on his penis. She cried out, and he was eventually forced to let go. I had a lot of trouble untangling in my head what this scene had placed there. Every time I tried to think about it, some unknown, and unwelcome turmoil rendered such meditation wearisome. At the end of the day, what harm had he done to me? A few weeks later, while she is working alongside her father, he has to leave suddenly and she is left with the apprentice. A band is going past in the streets and she wants to see. The apprentice raises her to the window, and in process, lifts her skirts and presses himself against her. She protests and he tells her he will put her skirt back, but starts caressing her genitals instead. She manages to escape again, and when she turns and sees his face, she is so afraid she nearly faints. This time she had to tell her mother everything. My mother's emotion and her expression of dismay overwhelmed me Her mother used the shame, and the desire to be rescued that Manon felt so strongly, to bring out her religiosity. Within a couple of months, Manon demanded to be sent to a convent.

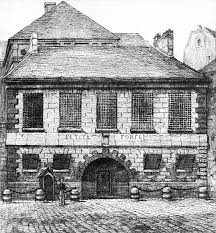

Manon meant to be scrupulous when recording her memories. But she did hesitate before relating the story of the assaults. She prefaces the story by saying that she is embarrassed by it, wanting her writings to be as chaste as she was. But, she says, it was too important a circumstance to keep a secret. Even as a child, she noted that telling the story to her mother required 'great courage' but that it was necessary. Olympe de Gouges was brought in to the Prison de l'Abbaye three weeks after Manon. The two must have overlapped, for a few days and maybe they talked, exchanged a few pleasantries. But Olympe was not the kind of woman Manon liked to talk to, not respectable enough, not mindful of her virtue or reputation. In any case, it’s unlikely that Olympe was in a talkative mood. A week earlier, she had cut her leg, falling off a car, and the wound was infected. The guardians at l’Abbaye decided they could keep her – it would not do for a prisoner of as high a profile as Madame de Gouges to die before she was tried. So she was transferred to another prison, the Petite Force, previously a prison for prostitutes, and the scene of the Princesse de Lamballe’s massacre the previous year, but now converted to an infirmary for prisonners. No doubt the conversion didn’t amount to much and Olympe did not want to stay there. She sold her jewels and paid to be transferred to a private pension for sick prisoners on the Chemin Vert. Unlike the Abbaye or the Force, this is a prison for both men and women, and soon, Olympe finds herself pregnant at the age of nearly forty-five. Only three weeks afterwards, on 28 October Olympe was taken to the Conciergerie and put there in isolation for four nights in the same cell where Marie Antoinette had spent her last days, just two weeks previously. Then on 2 November, she is tried. As she is accused of having printed a pamphlet against Robespierre, raising the possibility of a constitutional monarchy, she cannot plead innocent. Not only had she written the pamphlet in question, the Three Urnes, but she had herself posted it on the walls of Paris, after her distributor deserted her. So instead of pleading innocence she pleaded pregnancy. She was examined and the doctors confirmed that there was a good chance she might be pregnant - but it was too early to tell. She herself testified that she recognised the signs, that had felt the same way on the two occasions she'd been pregnant before. (This is, incidentally, the only mention of a second child, who must sadly have died). Her prosecutor, the infamous Fouquier-Tinville, however, refused to consider the evidence on the grounds that she had been in a female only environment (conveniently forgetting her stay at the Chemin Vert pension). The next day, Olympe climbed the stairs up to the Rue de Mai, stepped into the charette, and was driven to her execution. Her last words: “Children of France, you will avenge my death!”

|

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed