|

According to Brissot, both the English revolution and Macaulay’s History were a significant influence on the American Revolution: The Americans lit their reason with the torch of those men, who were enlightened in a century when nobody was. It is enough to be convinced of it to read the excellent history of Miss Macaulay, and to compare what this excellent woman says about the sevellers(sic) whose principles she set out so well, to all the public writings of Americans during the troubles. Macaulay, encouraged by the warm friendship of her correpondents, and the success of her history in America decided to travel to that country, for the purpose of writing about the American Revolution. During that time she was hoping to gather material for her book, but also to find support for the publishing of it. In that, Brissot tells us, she was disappointed: She was admired everywhere she went, but no one paid a subscription for her History. Deceived in her speculation, and in the support she had excepted, she came back discgusted by the Americans. Her anger was unfounded. At peace, empoverished Americans only thought of rebuilding their farms and cultivating their lands. They only read newspaper, which, despite their cheapness, they could ill afford. Few books, aside from the Bible, were being sold in America, and if you look at the list of subcribers for Gordon’s History of America, you will be surprised to find that three quarters were English. Macaulay died shortly after her trip. One might be tempted that she would have received more support had she been a man – she could, like Paine, have become the cossetted darling of the Americans. However, Paine went to America before the war, before the Americans became strapped for cash. Brissot experienced something similar to Macaulay – when he travelled to America to find a place to settle with his family, he tried to enlish patrons, people who would help him establish himself there as a writer. He too came back disappointed.

0 Comments

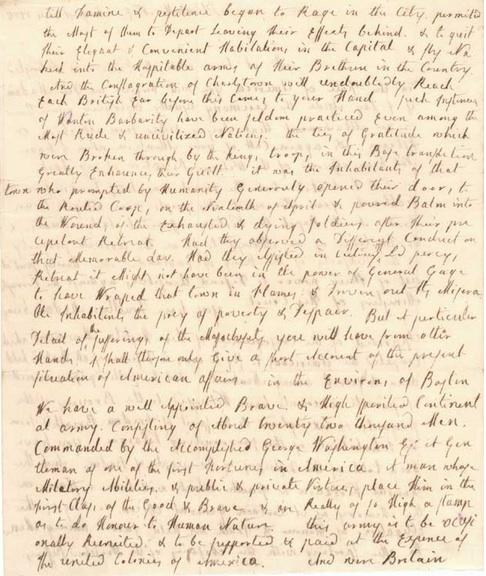

Jacques-Pierre Brissot, Manon Roland’s close friend and republican ally, also visited England. Brissot was a lower-middle class provincial who trained as a lawyer, but came to Paris and decided to become instead a writer and journalist. One of his first jobs was for the Scotsman Samuel Swinton, the editor of the Courier de l’Europe which reported on English politics in several languages. Brissot was his French editor. It is in that capacity that he first travelled to England in 1779 at the age of 25. This first journey was short – two weeks – but it gave him a taste for England. This taste became more pronounced as the young writer came up against the stringent French censorship laws, and again when in 1782, he married Felicite Dupont, who translated English writers Goldsmith and Dodsley, and who had spent some of her childhood in London. The couple moved to London shortly after they married. Brissot, who was hoping to establish himself as a writer there was disappointed. As a foreigner, I was snubbed, he says, except by a few individuals, the principal one being Catharine Macaulay. Catharine Macaulay (1731-1791) was only fifty-one when Brissot met her. Yet, he describes her as a very old woman: Imagine a woman with lead on her face, missing teeth, wrinkles badly hidden with rouge, and whose decrepitude showed beneath her always fashionable and elegant get up. Next to her the brilliant figure and freshness and health of her husband, still an adolescent! It looked as if a child was hugging a corpse. Macaulay’s marriage to a twenty-five year old (hardly a teenager!) and good looking man had of course been badly received, and even Brissot, who admired her greatly and defends her against other accusations (such as that she was not the author of her own works) finds this difficult. But even then Brissot tries to dispel the calumnities by arguing that it was the family of her husband (his brother was some sort of medical innovator or quack) that was really objectionable. Macaulay’s most famous work was her History of England in eight volumes. Brissot thought that work remarkable, and beleived that she deserved the laurels she had taken from David Hume. To objections that she could not, as a woman, really be the author of that work, Brissot replied that the evidence that she was laid in her conversation: ‘It has all the characteristcs, he said, of the dignity, the republican energy breathed by her History.’ |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed