|

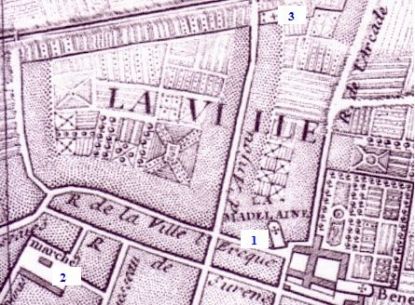

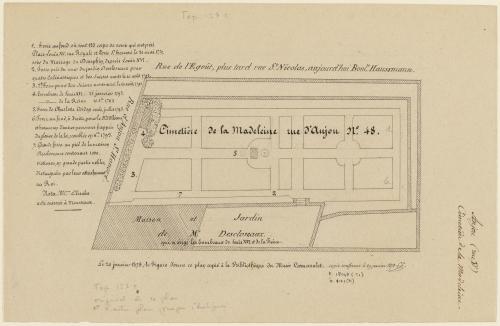

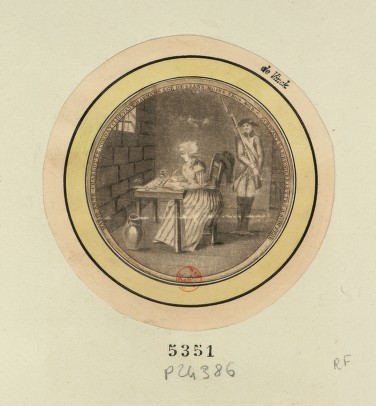

The revolutionary period, in particular the Terror, was hard on the Paris graveyards. Many people died in massacres and at the Guillotine who had to buried in the already full graveyards. When the body counts started to rise, the Parisians needed somewhere to pile up their dead. The site of the church of Sainte Madeleine, first opened in the 13thcentury was located roughly where 8 Boulevard Malherbes now stands. It had a very small cemetery and a slightly larger one was built in 1690, on land that was closer to the Faubourg Saint Honore, already a posh neighborhood. In 1720, the cure of la Madeleine sold a large tract of land to be convereted to a graveyard. The graveyard was built on a large rectangle of 45 by 19 meters surrounded by a wall. It filled up slowly at first, but in 1770 it received its first mass burial. On the occasion of the celebrations of the wedding of Louis the Dauphin and Marie-Antoinette, a show of fireworks was given to the people of Paris. This was a novelty, and more scary than exciting for many. There was a crush in the crowded streets and several hundred people died. These were buried in the Madeleine. The next large scale burial happened in August 1792, when the Paris revolutionaries, assisted by the Marseillais massacred the King’s Swiss Guards. Their mutilated bodies were thrown into the Fosse Commune at the Madeleine. By then it was summer, and the smell in the neighborhood became unbearable – someone reported it at the assembly, but it was decided that the risk of false rumours of a plague epidemic was too great if a fuss was made, and the subject was dropped. The rich inhabitants of the quartier would just have to put up with it. The location of the Madeleine was also very convenient for transporting bodies from the Place du Carousel and Place de la Revolution – the guillotine’s first two locations. Légende - Au recto, à gauche sur l'image, à l'encre, inscriptions correspondant à la numérotation de l'image : "1. Fosse au fond où sont 133 corps de ceux qui ont péri / Place Louis XV, rue Royale et Porte St. Honoré le 31 mai 1770, / soir du Mariage du Dauphin, depuis Louis XVI." ; "2. Fosse près du mur du jardin Descloseaux pour / quatre Ecclésisatiques et 500 Suisses morts le 10 août 1792." ; "3. 2e. Fosse pour 500 Suisses morts aussi le 10 août 1792" ; "4. Tombeau de Louis XVI. 21 janvier 1793. / -id- de la Reine 16 8bre 1793" ; "5. Fosse de Charlotte Corday seule, juillet 1793." ; "Fosse au fond, à droite, pour le Dc. d'Orléans / et beaucoup d'autres personnes frappées / du glaive de la loi ; comblée en Xbre. 1793." ; "7. Grande fosse au pied de la maison / Descloseaux contenant 1000. / victimes, en grande partie nobles, / distinguées par leur attachement / au Roi. / Nota. Mme. Elisabet / a été enterrée à Mousseaux.". Date et signature - Au recto, en bas à droite, à l'encre brune : "copie conforme le 29 janvier 1878 LL". - From the Musée Carnavalet. Eventually, in March 1794, the Madeleine was closed and the next victims of the Guillotine were buried elsewhere. But before then, more famous bodies were entered there, including the King and the Queen, many of their supporters and family members, Charlotte Corday – who benefitted from a single occupancy plot, the twenty-two Girondins (including Brissot) who died on 31 October 1793, and of course Manon Roland and Olympe de Gouges.

During the restoration, Louis XVIII built a chapel to the memory of his brother and sister in law. Small chapels were added later to commemorate the other victims of the Revolution.

0 Comments

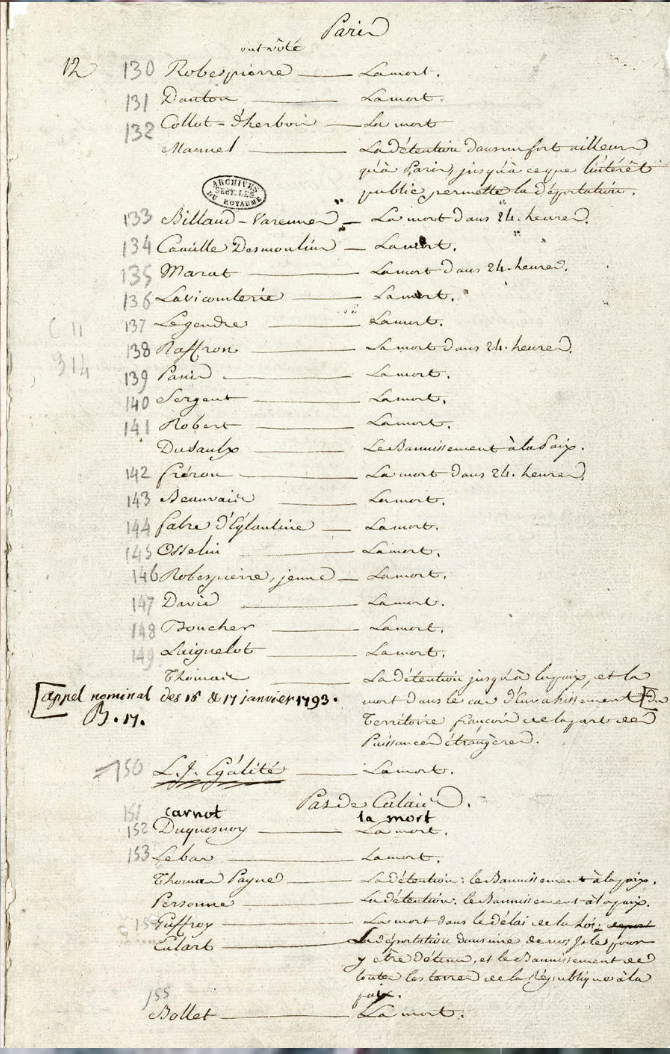

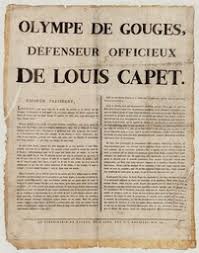

Around the time that the guillotine was first tried, Sophie de Grouchy was finishing a draft of her Letters on Sympathy. The letters are a both a commentary and a response to Adam Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments in which the Scottish philosopher argued that morality arises out of our reactive attitudes and the sympathythat human beings naturally feel for each other. For Grouchy sympathy develops from the first relationship an infant experiences, that is from the proximity with another living body, and the dependence it develops with it. Because sympathy is developed through contact with others, it is natural that the Letters discuss crowd psychology: Amongst the effects of sympathy, we can count the power that a large crowd has to affect our emotions [...]. Here are, I believe, a few causes of these phenomena. First, the very presence of a crowd acts on us through the impressions created by faces, discourses, or the memory of deeds. The attention of the crowd commands ours, and its eagerness, forewarning our sensibility of the emotions it is about to experience, sets them in motion. This passage is reminiscent of the Roman Stoic philosopher Seneca’s Letter to Lucilius, in which he describes the powerful – and worrying – effect that crowds can have on the wisest, calmest of individuals. He writes how, on occasions when the emperor forced him to attend gladiator shows, his blood was raised and he too wanted to shout that one should die and another live. To consort with the crowd is harmful; there is no person who does not make some vice attractive to us, or stamp it upon us, or taint us unconsciously therewith. Certainly, the greater the mob with which we mingle, the greater the danger. Grouchy tried to pinpoint the cause of this response. It is the overwhelming presence of living bodies, all in one place, all speaking, moving, twitching in their own way, but at the same time all focusing their attention on the same point, which both confuses us and takes over our own sense of direction: we too want to look where they look, and we too are getting excited with the anticipation of what will happen there. The description of the effect of crowds in the Letterson Sympathyalso touches on the paradox of tragedy – why do we enjoy tragedy so, if we find other’s pain distasteful? The question is as old as Aristotle, who saw in tragedy a way to educate one’s emotion, to learn to understand and manage them. This is also where Grouchy is going here: In any case, we know that the spectacle of physical suffering is a real tragedy for the masses, a tragedy they seek only through a dumb curiosity, but whose sight sometimes arouses the kind of sympathy which can become a passion to contend with (Letter 4). No doubt Grouchy also has the spectacle of the public execution in mind here. When she first drafted the letters, executions were most commonly hangings, and they were always public, in France as elsewhere. People came to watch, and bought snacks and souvenirs, as they would at the theatre. And as we know, a year after writing this, she mingled with the crowds going to the guillotine, in order to visit her husband in hiding. On 15 January 1793, Louis Capet, previously King of France, is found guilty by an overwhelming majority of the 749 deputies. Two days later, the deputies are asked to vote for a penalty. 346 vote for the death penalty. Others, including Thomas Paine, who had been offered honorary French citizenship, vote for exile, or for imprisonement. . One citizen, who had not voted, argued against the death penalty. Olympe de Gouges started by offering herself as Louis’s unofficial advocate on 16 December, arguing at first that while as a King, he had done harm to the people of France by his very existence, once Royalty had been abolished, he was no longer guilty. As king, I believe Louis to be in the wrong, but take away this proscribed title and he ceases to be guilty, in the eyes of the republic. This proposal, written as a letter to the Convention, was then printed as a placard and distributed throughout Paris. The Convention disregarded the letter. Sèze was made Louis’ advocate, and the argument that Gouges put forward was not taken into consideraton. Louis Capet, stripped of his title, was still tried for high treason, i.e. for actions he had performed while he was still King of France. Olympe did not stop at this. On 18 January, after the King had been found guilty, but before his death had been voted, she put up another placard addressed to the Convention and to the people of Paris, entitled “Decree of Death against Louis Capet, presented by Olympe de Gouges.” In this piece she also attempted to dispel the mistaken impression that she was in fact a royalist. Louis dead will still enslave the Universe. Louis alive will break the chains of the Universe by smashing the sceptres of his equals. If they resist? Well! Let a noble despair immortalize us. It has been said, with reason, that our situation is neither like that of the English nor the Romans. I have a great example to offer posterity; here it is: Louis' son is innocent, but he could be a pretender to the crown and I would like to deny him all pretension. Therefore I would like Louis, his wife, his children and all his family to be chained in a carriage and driven into the heart of our armies, between the enemy fire and our own artillery. (http://www.olympedegouges.eu/decree_of_death.php) Here Gouges is appealing to a well-known fact about the workings of royalism: a King cannot die. The holder of the title may die, but the title passes automatically to the next contender, without, even, the necessity of sacrament. The immortality of the king was such an important precept that a Chancelier, when a monarch died, could not wear mourning. Bossuet captured the phenomenon thus in his Mirror for Kings: Letting Louis live, she would go on to argue in her final published piece, 'Les trois urnes'. would have made it clear that he was no longer a threat to the republic - as no one individual is. To execute him is both to betray a certain lack of confidence in whether the people have truly succeeded in aboloshing the monarchy, and perpetuate that doubt, as after Louis's death, his title is transferred to his descendent.

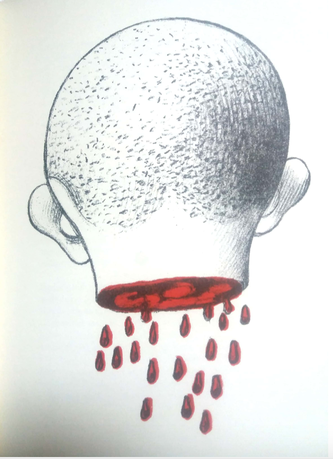

During a recent visit to the Conciergerie, I picked up a prettily bound book, entitled Note sur le supplice de la guillotine. The book contained a short essay of that title by Cabanis, five drawings by the artist Cueco, and a discussion of the moral and political philosophy of the guillotine by French philosopher Yannick Beaubatie. For the main part, Cabanis's article, written 1799 (an IV) argues against recent articles that claimed that the torment of the guillotine ought to be abolished because it cannot be proven that the guillotined do not feel pain. The articles (by members of the medical profession, Cabanis's own colleagues), cite as evidence witnesses's reports of decapitated heads moving in such a way as to suggest that they responded to the situation, and attempted to communicate. One example they cite is that of Charlotte Corday, whose decapitated head was slapped by one of Sanson's valets, after which it apparently reddened as if in shame and indignation. Cabanis answers that while he was not present at any decapitation (as he did not have the stomach for it) he was present at the testing of the machine and certifies that death must be instanteanous. He then goes on to discuss the philosophical question of where pain resides, and the medical phenomenon of bodily movement after death. At the end of the essay, Cabanis offers his moral and political reflections: the death penalty, he claims, ought to be abolished. But if it is not, the guillotine has to go. Not because it causes pain to its victim, but because it is too swift so that as a performance of a punishment it cannot serve its rightful purposes. Beaubatie takes this up in a fascinating discussion. In particular, he notes a resemblance between Cabanis' s reservations about the guillotine and Beccaria's utilitarian theory of punishment. Beaubatie notes further that Beccaria and Cabanis both frequented the Helvetius home, although two years apart. What Beaubatie does not note, however is the strong resemblance between Cabanis's thought and that of his sister in law and long term friend and collaborator Sophie de Grouchy. Cabanis's principal reason for thinking that the guillotine should not be used is not - as Beaubatie claims - that it cannot serve as an exemple or detterrent, but that it does not allow enough time for spectators to react emotionally in such a way that would help their sympathy grow. The guillotine’s work is done in less than a minute. That it did not occur to Beaubatie, in his commentary written in 2002, to look to his long term philosophical correspondent Sophie de Grouchy for influence, as well as to Beccaria (whose path with Cabanis crossed, but two years apart) is a sign of how much work has been done over the last fifteen years in recovering the works and influence of women philosophers. Charlotte Corday died at the guillotine in July 1793, a few weeks after Manon Roland’s arrest, and a few days after Olympe’s. Charlotte had come down from her native Vendee, in the north west of France, just below Britanny, to murder Jean-Paul Marat, the ‘friend of the people’ and leader, with Robespierre, of the Terror. She was an aristocrat, who left to her own devices, had ‘read everything’ in her parents’ library. She was a republican, who wanted to save the republic by ridding it of Marat, and not, as the English believed at the time, a royalist. She came to Paris, rang Marat’s door bell, was admitted to his bathroom where he was writing in the tub, to relieve a skin irritation, and she stabbed him. She was arrested immediately and tried very publically. A few days later she died. When we talk about women who were important actors in some historical event or other, very often there is a focus on what they looked like, in particular, whether they were pretty or not. (This, of course, does not simply apply to political women from the past but is still very much in force!) What's interesting about Corday's case, is that descriptions and portraits of her after she was caught are very different from earlier descriptions or portraits. Before the murder, Charlotte Corday was described as pretty, beautiful even, by all who saw her. Even Chabot, the Montagnard who thought her a horrifying accident of nature, and fancied he could detect plainly her criminal propensities painted on her face, still described her as having ‘spirit, grace, superb height and bearing,’ But the death of Marat changed the way she was perceived. Fabre d’Eglantine, actor and Danton’s private secretary, captured this reversal in his ‘Moral and physical portrait’ of Corday for the daily newspaper Le Moniteur Universel. “This woman who has been called very beautiful was not beautiful. […] she was a virago, fleshy and not fresh, without grace, dirty, as are nearly all female philosophers and blue stockings. Her face was covered in red patches, and featureless. Height and Youth are proof indeed! That is all it takes to be beautiful while on trial. Moreover this observation would not be needed if it were not for the general truth that any woman who is beautiful and knows it cares for life and fears death.” |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed