|

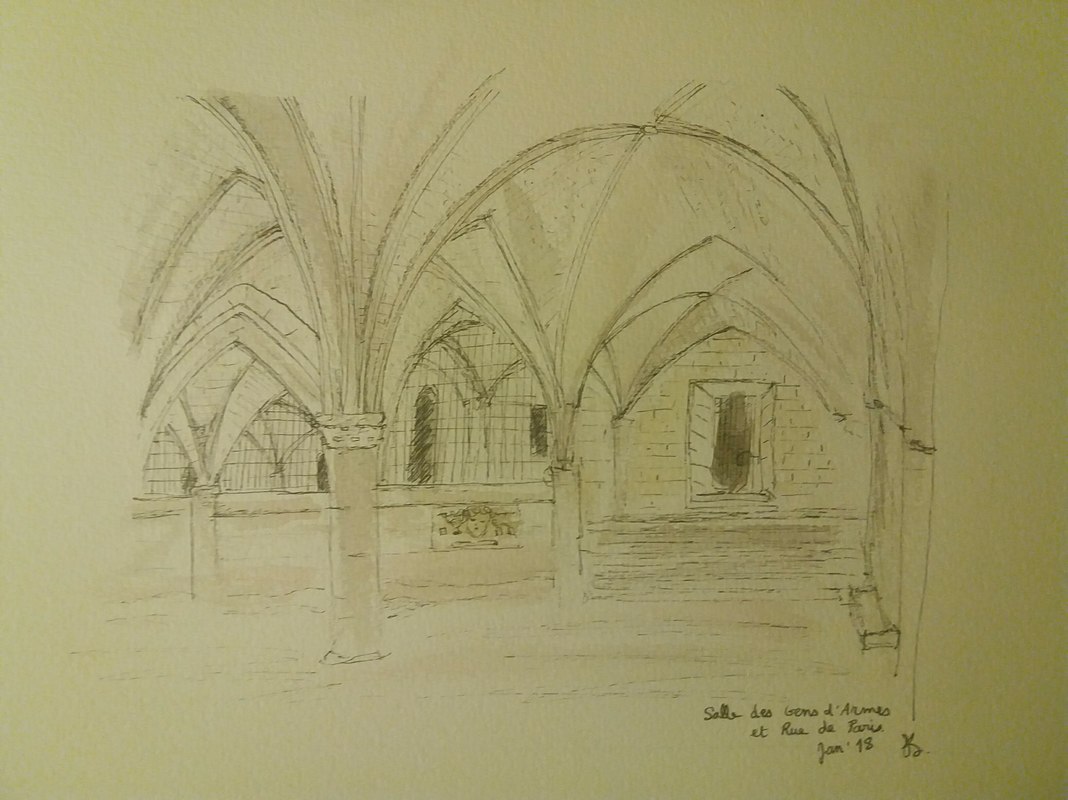

The gift shop of the Conciergerie is situated in a narrow room at the back of the largest medieval room in Europe, La Salle des Gendarmes. The narrow room is called Rue de Paris, after "Monsieur de Paris", an affectionate nickname for Charles0Henri Sanson, the executioner of the Revolution.

The Rue de Paris was what prisonners who could not afford to pay for a private cell walked through in order to reach the large room where they would stay until their trial along with hundreds of others. Private cells were called 'A la Pistole', because it cost a Pistole per night to stay there, a Pistole being a Louis d'Or, so a substantial amount of cash. Those who could not afford this were called 'Pailleux' because the room where they stayed was covered with (dirty) straw. Men and women were kept separately, and aside from Marie Antoinette's cell, and the women's courtyard, the Conciergerie has only reconstituted the living quarters of the male prisoners. This leaves us to speculate as to how women were accommodated. We know that Manon Roland was not rich, but yet she spent her last nights at the conciergerie on a bed - given her by another prisoner - rather than in the straw.

0 Comments

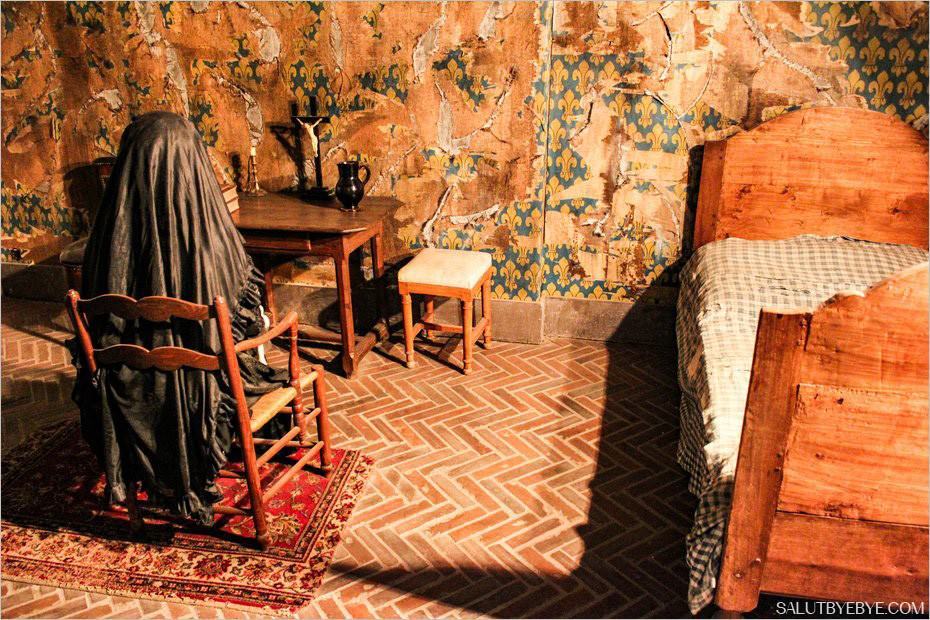

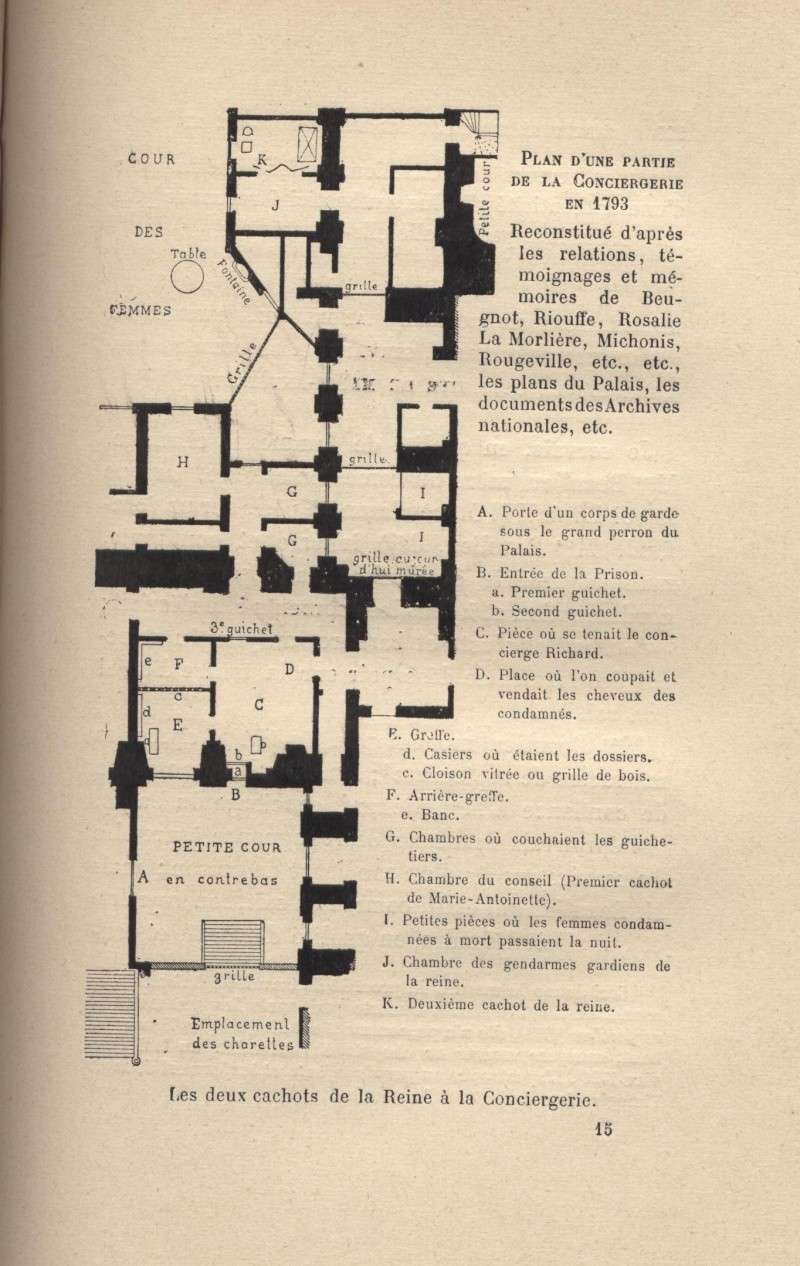

On 2 November 1793, Olympe de Gouges was tried, and declared herself to be pregrant. She was examined by a team of two doctors and a midwife who found the signs to be inconclusive (it was too early to tell). She was executed the next day. Where did the examination take place? Either in her cell, which is reputed to have been the same as Marie-Antoinette's second cell, or in the infirmary. Marie-Antoinette was moved from one cell to another when she attempted to escape through a trap door, on her way between her first cell and the women's courtyard. The second cell was isolated from the others. A wall was built to cut it in half and guards were posted in the other half to prevent any further attempted rescue. This was the cell Olympe was taken to, as she had to be kept 'au secret', unable to communicate with anyone who might have taken a letter to her friend Cubiere (who could still have saved her, perhaps). Because this cell was Marie Antoinette's it was preserved. But the rest of that floor was transformed, in part for Louis XVIII to build a chapel in Marie-Antoinette's memory. The infirmary no longer exists, but it was described by one of the inmates of the prison, Le Conte de Beugnot as a long room, 25 by 100 pieds (around 8 by 32 meters), with a vaulted roof, grilles on both sides and illuminated by two narrow windows. Looking through old maps and descriptions tells us very little as to where the infirmary might have been, except that it was supposedly just outside of Marie Antoinette's cell. Still, I decided that I knew the Conciergerie well enough to have a shot at finding traces of the infirmary. For one thing, I knew where there was a narrow window that was close to Marie-Antoinette's second cell. The turett was clearly part of the 19th century building, but it seemed as though the window below it may have existed in a previous incarnation of the first floor. So off I went with my team of investigators - my daughter, who'd already participated in the Revolutionary Paris tour and helped research this post ; my mother, who's often finding information for me, my son, whose first visit to the Conciergie this was, and who was mostly extremely patient, and my nephew, whose excellent detecting skills proved to be invaluable Although the Conciergerie is one of my favourite buildings in Paris and one I know well, I don't think I had noticed until now how much of it was recent. Despite its looming medieval towers, and the large medieval room, most of it dates from the 19th century, and very little remains of the revolutionary period. This may be because a lot of the cells were constructed during the revolution, in a hurry, in order to accommodate the increasing number of prisoners. The first thing we noticed was that the building of the chapel had meant the destruction not only of the floor it was on, but that part of the top floor was also missing. Marie Antoinette's cell itself was clearly marked out as older, with a brick floor, slightly lower than the floor of the chapel. This was where the infirmary supposedly begun. But where did it go? We walked out to the women's courtyard, where women went to walk, and talk, and wash their clothes in the fountain. The turret where I'd seen the narrow window was on the wrong side, i.e. near the Palais de Justice and not apparently connected to the building where Marie Antoinette's Cell was. After some walking around and a fruitless attempt to question a man who worked in the museum (what? he did not know the entire, precise history of the building?!) the children worked out that there must have been another turret, roughly opposite the existing one, and at a place where the infirmary would have passed. We still have but a very vague view of where this place was. But at least we've had a shot at reconstructing it. More importantly, perhaps, we came out with a much stronger understanding of how elusive the past is, even when it is set in stone. The ghosts of the revolution may still walk the corridors of the Conciergerie, but these are not the same corridors that we walk as tourists.

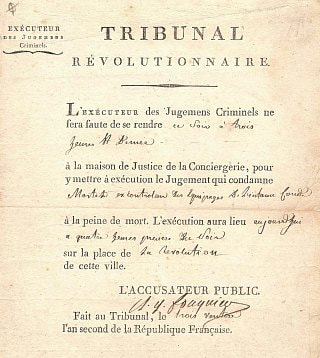

Olympe was tried at the Conciergerie on 2 November 1793. After she was arrested on 20 July she had been held first, at the Prison de l'Abbaye, transfered to the hospital prison of La Petite Force - she was suffering from an infected cut on her leg - and finally she paid to be incarcerated at a private pension on Chemin Vert. The public prosecutor of the Revolutionary Tribunal was Antoine-Quentin Fouquier-Tinvinlle, a zealous and ruthless officer of the Terror, who took his turn at the Guillotine in 1795. Olympe was introduced as 'Marie Olympe de Gouges, veuve Aubry. born in Montauban, aged 38 (she was in fact close to 45), residence: rue du Harlay section du Pont Neuf'. She was charged with' having composed a work contrary to the expressed desire of the entire nation', and according to Article 1 of law of 29 march 1793: Whoever is convicted of producing writings advocation for the dissolution of national representation [...] will be sentenced to death." she was sentenced to death by the guillotine. She would have been excecuted on that same day, but, after the order was read, she announced that she was pregnant. 'My enemies will not have the glory of seeing my blood flow. I am pregnant and will bear a citoyen or citoyenne for the Republic' According to the law, she was to be examined by health officers who had been named by Robespierre 8 months previoulsy, after the Revolutionary Tribunal was founded, and by a Midwife, Veuve Prioux. Her cell at the Conciergerie was the same one Marie-Antoinette had been held in after her attempted escape. It was isolated, for the purpose of keeping prisoners 'au secret'. The infirmary was just outside that cell, a dire place, if we are to believe the description of a surviving prisoner, Beugnot: Seven by thirty metres, closed on both sides by iron fences, two narrow windows, vaulted roof, like some sort of gothic hell. 40 or 50 dirty straw beds on either side, with two or three patients each, sharing unwashed blankets. The privies were in the middle of the infirmaries, and there sick patients who had collapsed on the way lay in their own waste. The corpses, three or four each day, were removed at a specific hour of day, and until that time, the dead remained in bed with the sick. All that is now left of this room is one of its narrow windows, which is visible from the women's courtyard. The medical team concluded that if Olympe was pregnant, it was too early to tell. Fouquier-Tinville chose to ignore their doubt, and declared that her claim had been found to be false: The Public Prosecutor notes that the accused was incarcerated for the past five months and that according to regulations no contact was allowed between men and women in prisons. Therefore she made it up in order to avoid the death penalty. There was in fact much romantic commerce between prisoners, as they were kept in adjoining wards, and often not very efficiently. In any case, Olympe had been staying in a private pension for mixed prisoners, a fact that Fouquier Tinville chose to ignore.

|

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed