|

Manon Roland did not live through a pandemic. But she did spend several months in forced isolation, when she was arrested and sent to prison, first at l'Abbaye, then at Sainte Pelagie. Did her experience bear any resemblance to ours, who have to self-isolate at home while Covid19 weakens and hopefully goes away? Certainly there are many points in common: Fearing for her friends' lives – check: those of them who were not also in prison were running, and in fact many of them died. Fearing for her own – check: and quite rightly too, as she was guillotined after 5 months of prison. Having to stay away from her loved ones to protect them – check: the motive for her arrest was that she might give away the whereabouts of her husband and other Girondins, including her lover Buzot, so she had to make sure that she kept her contacts with them very discreet indeed. Being confined to a small indoor space, without all her work stuff – check: Though her first cell was fairly comfortable, she was moved somewhere smaller. And though she had some books sent to her, and was able to buy pens and papers, most of things were inaccessible under seals. Knowing the world around her was falling to pieces because its leaders were mad and not having a clear idea of when it would all be over – check: she saw the Terror as the death of the Revolution and did not think the republic would ever recover. How did Manon cope with isolation? Not being ill, and being completely isolated from anyone she may have had to care for or homeschool, such as her daughter, Eudora, she could use the time pretty much at her own discretion: I plan to use the leisure of my captivity by retracing my personal life from my earliest childhood until now. To go back thus, on every step of one's career is to live a second time. And what better is there to do in prison than to take one's existence elsewhere through a happy fiction or interesting memories? How did she manage to settle down to work in such circumstances? Manon tells us that her education, which mixed Plutarch with omelet making, and dancing lessons with Latin was an ideal way of preparing for a varied life, and especially useful for knowing how to make the best of a very unpleasant situation: This mixture of serious study, pleasant exercise and ordered domestic tasks, seasoned by mother's wisdom, rendered me fit for everything. This seemed to predict the vicissitudes of my fortune and helped me bear them. [...] I am nowhere out of place. So when she first arrived at l'Abbaye, her first prison, she immediately set about to organize herself, so that she would be comfortable and able to work: Up at noon, I examined how I would settle in my new home. I covered a small and mean table with a white cloth and placed it under the window, intending to use it as a desk, resolved to eat at the corner of the hearth in order to keep my work space clean and tidy. But before you ask yourself how you could be more like Manon, and make your quarantine more productive and tidier at the same time, remember that Manon died at the guillotine. Don't be like Manon. Stay safe.

0 Comments

When Manon Roland was at the prison of Sainte Pelagie, she found at first the company a bit too loud for her tastes: the prison was full of prostitutes and thieves whose ribald jokes she could hear through the thin walls of her cell. So when an old acquaintance Louise Petion was brought to Ste Pelagie, Manon was saddened, of course, but also relieved: she now had some company.

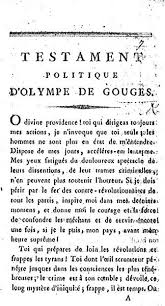

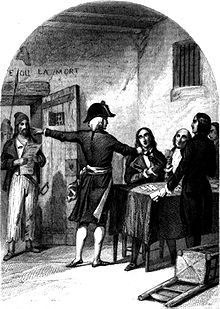

Unfortunately their friendship was tinged with tragedy. In September 1793, when she heard of the arrest of her daughter, Louise Catherine Angelique Ricard, veuve Lefevre, came to Paris to petition for her release. She was in turns arrested, and take to the Conciergerie. Almost immediately she was tried and condemned to the guillotine on the grounds of defending the re-establishment of monarchy. She is reputed to have claimed, when asking for her daughter's release, that Brissot and Petion and the proscribed Girondins were true republicans, and that if the French people wanted a king, they should have one. She was executed on 24 September 1793, at the age of 56, her daughter was still in Ste Pelagie. When Manon visited with her friend, she would have been dealing with the loss of her mother, but also been fearing for her husband. Jerome Petion had escaped with Buzot, Manon's lover (although the relationship was a secret, so Manon could not tell Louise that he was that). Petion and Buzot died together in a suicide pact. Their bodies were discovered in a forest, eaten by wolves. Louise-Anne Lefevre eventually came out of Ste Pelagie and, after the Terror, was granted a widow's pension. Her son, Jerome, lived on and pursued a military career under Napoleon. Olympe was arrested on 20 July 1793. Three weeks before that, she was moving her furniture from Paris to a small house she had bought in the countryside near Tours, and where she was about to retire. She had been away visiting properties and spending time with her son, but had come back to Paris to see to the removal of her things. Olympe knew that by being in Paris, and publishing more political tracts, she was putting herself at risk. But the decree against the Gironde had just been issued and she felt she had to do something. Her Political Testament, written at time, reflects her anger and uneasiness: If, in a final effort, I can still save the republic, (chose publique), I desire that even while they immolate me to their fury, my sacrificers still envy my fate. And if one day, posterity notices women, perhaps the memory of my name will be of value. I have planned everything. I know that my death is unavoidable, but how beautiful and glorious it is, for a well-born soul, when ignominious death threatens all good citizens, still to give one's life for our dying country! Her next tract, The Three Urns, is an attack on the Paris Commune. It is printed by her imprimeur, Longuet, on 15 July. He draws 1000 copies. She sends a copy to the committee of public safety, and one to Herault de Seychelle, then she waits a few days - no reply, which she takes to mean that she can go ahead. Her distributer, or afficheur, is a Citizen Meunier who lives in the Rue de la Huchette. On 20 July, Olympe leaves her apartment on the Ile de la Cite, crosses the bridge St Michel, and turns left into the Rue de la Huchette. The Pont St Michel and the Rue de la Huchette are still there. The actual Pont St Michel dates from the mid-nineteenth century. Earlier photographs show a similar looking bridge, with four arches, rather than two, and less flat. And back in the eighteenth century, it would still have had the more traditional aspect of the Medieval bridge, it would have been covered in wooden shops and houses. The members of the Commune are reputed to have met in a tavern on the Rue de la Huchette. If true, this may well have influenced Meunier's decision not to post Olympe's Three Urns. What he actually told her, on the morning of her arrest, is that he was worried that it would rain. One imagines Olympe looking up at the clear sky, puzzled, before she set out to find another distributor on the Pont St Michel. But when she got there, Meunier's daugher, who had followed her pointed her out to three policemen and members of the national guard, She was arrested her and taken to the Depot prison of the Mairie.

Olympe de Gouges was brought in to the Prison de l'Abbaye three weeks after Manon. The two must have overlapped, for a few days and maybe they talked, exchanged a few pleasantries. But Olympe was not the kind of woman Manon liked to talk to, not respectable enough, not mindful of her virtue or reputation. In any case, it’s unlikely that Olympe was in a talkative mood. A week earlier, she had cut her leg, falling off a car, and the wound was infected. The guardians at l’Abbaye decided they could keep her – it would not do for a prisoner of as high a profile as Madame de Gouges to die before she was tried. So she was transferred to another prison, the Petite Force, previously a prison for prostitutes, and the scene of the Princesse de Lamballe’s massacre the previous year, but now converted to an infirmary for prisonners. No doubt the conversion didn’t amount to much and Olympe did not want to stay there. She sold her jewels and paid to be transferred to a private pension for sick prisoners on the Chemin Vert. Unlike the Abbaye or the Force, this is a prison for both men and women, and soon, Olympe finds herself pregnant at the age of nearly forty-five. Only three weeks afterwards, on 28 October Olympe was taken to the Conciergerie and put there in isolation for four nights in the same cell where Marie Antoinette had spent her last days, just two weeks previously. Then on 2 November, she is tried. As she is accused of having printed a pamphlet against Robespierre, raising the possibility of a constitutional monarchy, she cannot plead innocent. Not only had she written the pamphlet in question, the Three Urnes, but she had herself posted it on the walls of Paris, after her distributor deserted her. So instead of pleading innocence she pleaded pregnancy. She was examined and the doctors confirmed that there was a good chance she might be pregnant - but it was too early to tell. She herself testified that she recognised the signs, that had felt the same way on the two occasions she'd been pregnant before. (This is, incidentally, the only mention of a second child, who must sadly have died). Her prosecutor, the infamous Fouquier-Tinville, however, refused to consider the evidence on the grounds that she had been in a female only environment (conveniently forgetting her stay at the Chemin Vert pension). The next day, Olympe climbed the stairs up to the Rue de Mai, stepped into the charette, and was driven to her execution. Her last words: “Children of France, you will avenge my death!”

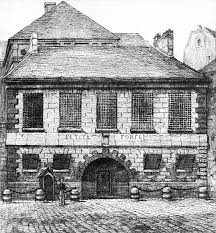

The prison de l'Abbaye was a 16th century prison, which was taken down in 1854 to make space for the Boulevard St Germain, On 1 June 1793, Manon Roland was arrested at her home on the Rue de la Harpe, a building which stood where number 35 now is. She was taken to l'Abbaye, on the corner of St Germain des Pres. In June 93, there were only eighty prisonners left in l’Abbaye. A few months earlier, before the September massacres, it had contained over 400. That is not to say that the prison was deserted when Manon first arrived, as one of her first sight, when she was brought in, was of five men lying on camp beds next to one another. The prison wardess apologised that she was not expecting her, and so has no room for her yet. But she found her a sitting room. There Manon set up a writing table, and her maid brought her Plutarch’s Lives, her favourite book since childhood, and Hume’s History. She’d have preferred Catharine Macaulay’s History of England, a republican text she had started reading the first few volumes in English, and that she greatly admired. But it was Brissot who had lent them to her, and an edict had been made for his arrest, along with twenty-one other Girondins, so Madame Roland surmised that he was probably not home. A week later, more prisonners arrived and she was moved to a smaller room – her sitting room could take more than one bed. Again, she set up a place to write, and in the little cell, which she kept as clean as she could, she recalled her childhood spent writing in her bedroom. Healthy and comfortable, and only worried for the sake of others – she read and wrote. Twenty-four days after she was arrested, she was set free again. She was almost reluctant to leave her peaceful cell, and only later did she learn that its occupants after her were her friend, Brissot, and then the famous Charlotte Corday. And on 20 July, Olympe de Gouges was brought to the Abbaye. As soon as Manon reached her front door, however, she was arrested again, and taken this time the the Pelagie Prison. She only left Pelagie to go the Conciergerie, the last prison of those who were condemned to the guillotine. I went to look at the Prison de l'Abbaye, or at least the space where it once stood. Rather incongruously, it is now a restaurant serving mussels and chips.

|

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed