|

History of Philosophy without any Gaps, in the Africana section, posted this week an interview by Doris Garaway on the Haitian Revolution, and it's (lack of) reliance on the Republican ideals of the French Revolution. Listen here.

0 Comments

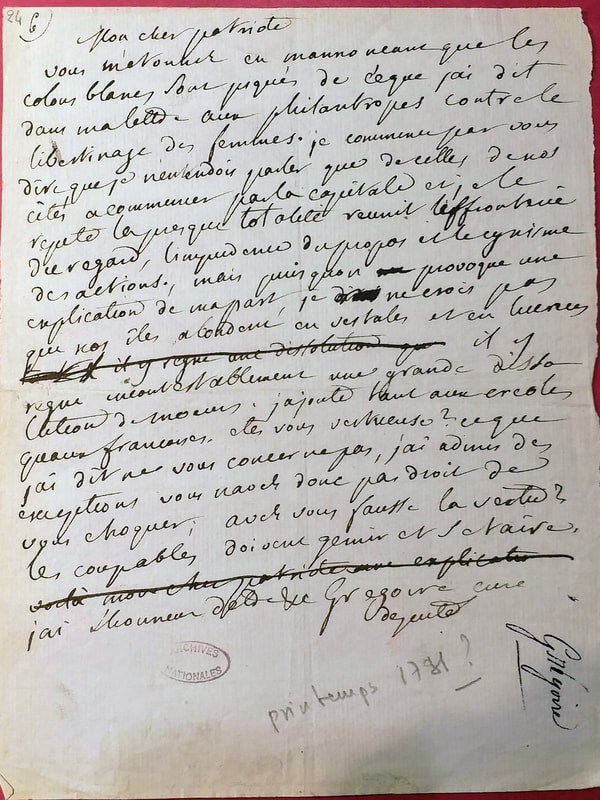

Henri Grégoire, known as the Abbé Grégoire, a catholic priest with jansenist sympathies, leading member of the Third Estate, Constitutional Bishop of Blois, was an important figure in the French Revolution, especially for his work against slavery in the French colonies. Grégoire, a close friend of Brissot, one of the few Girondins to survive the Terror, kept on fighting for abolitionism until his death in 1820. Given their shared enthusiasm for abolition, and the fact that they moved in the same circles it may seem surprising that his name and Olympe de Gouges' are not found together more often, or that there is no correspondence between them. When I was in the Archives Nationales, I found out why: Grégoire may have a great abolitionist, but his treatment of women did not measure up. The first clue as to Grégoire's attitude is a footnote from his 'Lettre aux philanthropes', (p. 19, note 1) written in 1790, to shame the French into action in the colonies: Readers, I confess to you, in great secrecy, a story about myself that the white colonists are murmuring to each other: 'it is not surprising that he defends the mixed bloods because his brother has married a woman of colour'. Honestly, if I did have a virtuous mixed-raced sister in law, I would prize her more than I do the near totality of your women, whose amiability receives such praise, but who cannot even, underneath their apocryphal modesty, conceal the ugliness of their vice; and who are all at once brazen in their gaze, impudent in their talk, and cynical in their acts. One might be prepared to forgive and forget – this is after all only a footnote, if it were not for a letter written to Brissot a few months later, in which he more than reiterated his views on women:

In other words, some women may be virtuous, most are not. Either way – women should shut up.

Vincent Ogé was a wealthy man of colour from Saint Domingue, a quarteron, in the terminology of the times. He found himself in Paris in 1789, and decided to stay after meeting first with Julien Raimond, and like him becoming a member of the Societé des Amis des Noirs. The Society, lead by Brissot, had previously been campaigning for abolitionism. However, they decided to support first the claim of men of colours to full political rights. Ogé and Raimond together petitioned the Assembly, but failed to convince it. With Brissot’s approval, Ogé decided that the next step was rebellion.

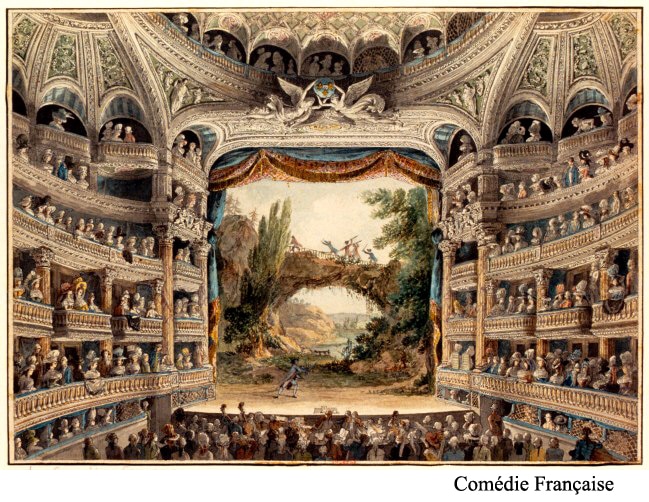

he travelled first to England, where her received support from Clarkson, then to Louisiana, where he is said to have purchased fire arms, and finally back to Haiti, where he led 300 men in a revolt. The revolt was quashed in less than a month. Ogé died on the wheel on 6 February 1791. In 1783 Olympe wrote her first play, Zamore et Mirza, ou l’heureux naufrage, and submitted to the Comédie Française. The actors liked it and accepted it. Unfortunately, her later dispute with Beaumarchais over Le Marriage Innatendu de Chérubin, meant that the Comédie just sat on her play and refused to put it on. The contract she had signed with them meant that it could not be played elsewhere in Paris. So Olympe took the play elsewhere, with her own theatrical troup, which included her son, and performed it in private theatres and in the provinces. In 1786, she had the play printed for the fist time. Two years later, she printed it again, with a postface, her “Réflections sur les hommes nègres” in which she explained what the philosophy behind the play was. Why are black people treated like animals, she asked? [I] clearly observed that it was force and prejudice that had condemned them to this horrible slavery, that Nature had no part in it and that the unjust and powerful interest of the Whites was responsible for it all. In 1788, Olympe was already sensing a change for the better in politics, and felt it her duties to show the world that if they wanted to redress injustice, slavery was the place to start: When will work be undertaken to change it, or at least to temper it? I know nothing of Governments' Politics, but they are fair, and never has Natural Law been more in evidence. They cast a benevolent eye on all the worst abuses. Man everywhere is equal. As she pointed out in January 1790, in an open letter to an (anonymous) American colonist attacking her play, at the time she wrote Zamore and Mirza, there was no organised French abolitionist movement. The Societé des Amis des Noirs did not yet exist. She ponders in that letter, whether it was her play that caused Brissot and the others to create that society, or whether it was just a happy coincidence: I can therefore assure you, Sir, that the Friends of the Blacks did not exist when I conceived of this subject, and you should rather suppose that it is perhaps because of my drama that this society was formed, or that I had the happy honour of coincidence with it. In fact, Brissot did take note of the play, and in the winter 1789, he made use of his growing influence to persuade the actors of the Comédie Française, finally to put it on. Unfortunately, the actors bore a grudge, so they arranged for the play to be put on on the last day of the year, after which Parisians would be returning to their family homes to celebrate the New Year. The contract required that a play make a certain amount of money in the first three days if it was to stay on the program. The first night was a success – but a political rather than an artistic one. People came to support it and to protest against it, and they were so loud about it, that few could hear the actors. Fortunately the text was in print, and reviewers at the time noted that they’d had to refer to the printed version to know how the play ended. Those who protested against the play most vociferously were the colonists, who had strong financial interest in the laws regarding slavery staying as they were. One such colonist wrote to Gouges, imputing that she was but the tool of Brissot’s society, and that her play was a call for the slaves of America to revolt. Gouges responded in an open letter, (1790) arguing, as we saw, that it was she, not Brissot, who’d first given voice to the abolitionist in France, and that her play did not incite revolution, but that it enjoined the French people and the colonists to see that all men were equal and abolish slavery, and the slaves to trust in the new laws and wait for a better future. Two years later, these accusations came back when the slaves and the free people of colour of Saint-Domingue revolted. Olympe de Gouges, when writing her play about slavery, Zamore and Mirza, or the Fortunate Shipwreck, displayed a certain amount of confusion about the geographical setting and the people she depicted. The play is described as an Indian drama. The Action is said to take in the East Indies. The main characters, Zamore and Mirza are described as Indians and another as governor of a Town and a French Colony in India. There are also 'several local indians'. Gouges describes a ballet that is take place at the end of the performance where Indians and soldiers mix, and which is to represent the discovery of America. In a postcript she added to the play, she recommended that the theatrical company 'adopt both the colour and the dress of the Negro.' thereby contradicting apparent claims that her protagonists are either Asian or native Americans. Although the French did colonize India, it is not clear that this is supposed to be the setting of the play. Rather, the West Indies is where the French had slaves. What about East Indies? The French did again colonise Vietnam, then Indochina, but this was not where the slave trade was conducted. On the other hand, the French East India Company had interest in Mauritius and Reunion (Ile de France and Ile de Bourbon), both, in the West Indies. The proximity of the West Indies to America may have led to the idea of a ballet re-enacting the discovery of America. What can we make of such racial ignorance and inept geography? Of course Olympe was largely uneducated. And the anti-slavery movement in France was yet to grow strong enough that many people were aware of the specifics of the slave trade and of the conditions of living in the West Indies. In fact, Gouges was one of those who helped bring the evil of slavery to the attention of the French public, and Brissot, one of the founders of the Club des Amis des Noirs, claimed to be influenced by her play, and offered her a membership to the abolitionist club as soon as it was founded. Olympe was ignorant, but she did not, as an 18th century woman, have much of an opportunity to educate herself by travelling. She was confused, but had good intentions: she felt that by portraying courageous, intelligent and compassionate runaway slaves, she would spread the word about the abuse that was perpetrated and interest the public in helping stop that abuse. Poor education, lack of opportunity, good intentions all sound like the sort of excuses given for every day racism and cultural appropriation. Does it make sense to see in Zamore and Mirza the beginnings of these phenomena? Ballet - at the end of the last act. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed