|

Not many in the eighteenth century agreed that women should be writers of anything other than gossipy letters. But even those who did found it hard to agree as to when was the best time for a woman to become a writer. A woman who had the misfortune not to be married or have children could write at any time, provided she did not disturb her relatives. Hence Jane Austen would get up early, before her family’s breakfast, and write at the dining table. Afterwards there was household tasks to attend to, of course, and any other time she could take up a pen was devoted to writing letters to family members who were away. Considerations of respectability only applied to respectable women, of course. So Olympe de Gouges, widowed, living under her assumed name instead of her husbands (Aubry), bringing up her boy alone, assisted financially by her lover, and pursuing a career as a playwright could write when she wanted to. This is probably why her biographer lists over 140 pieces penned by Olympe in the last five years of her life. (Her writing career began 1788 and she died in 1793) Little is known of Sophie de Grouchy’s writing habits, except for a report from her aunt that as a twenty year old, staying in a convent finishing school in Normandy, she spent so much time reading and translating that she made herself ill and damaged her eyesight. Given that the social life of the school was quite active – the idea was for the young women to be presented to society and hopefully find husbands – Sophie probably worked during the night, by candlelight. The only obstacle standing between her and her work then was her social life, and it is likely that even when she married and became a mother this carried on, i.e. that her activities as a saloniere were the only thing that stopped her from writing when she wanted to. Her daughter, Eliza, had a wetnurse, so that Sophie was not bound by the usual duties of motherhood. Manon Roland was firmly opposed to wet-nursing, being a follower of Rousseau, and a middle class woman, less able to ‘adopt’ a nurse, i.e. invite a woman to become a permanent member of the family and live under their roof until she could be retired. Manon also had some duties at home. Even though she had servants, they had to be trained, supervised, their work had to be done for them when they were sick and big jobs, such as laundry, had to be shared, and dinner had to be ordered, and prepared by herself when she wanted something done in a particular manner. And most importantly, children – in her case a daughter, Eudora – had to be educated following Rousseauian precepts. But none of this, Manon reflected, ought to take particularly long, so that a good mother and housewife ought still to have plenty of time for study and writing. Those who know how to organize their work always have leisure time. It is those that do nothing that lack the time to do anything. Moreover it is not surprising that women who spend their time in useless visiting and who think they are badly dressed if they have not spent a great deal of time at their mirror, find their days too long through boredom and too short for their duties. But I have seen those we call good housewives become unbearable to the world and even their husbands through a tiresome attention to little things. Manon’s stance was not unlike that of Mary Wollstonecraft, who claimed that a married middle class woman with children was in an ideal position, once her children were at school and no longer needed her full time attention, to take up science, literature or the arts. And did they pursue a plan of conduct, and not waste their times in following the fashionable vagaries of dress, the management of their household and children need not shut them out from literature, nor prevent their attaching themselves to a science, with that steady eye which strengthens the mind, or practicing one of the fine arts that cultivate the taste (VRW). Both in Roland and Wollstonecraft’s case, however, the life plan that would allow women to write while mothering young children relied very much on a reformed, republican and proto-feminist model of family life in which only necessary household duties were perfomed - the ‘vagaries of dress’ to be avoided and ‘if men do not neglect the duties of husbands and fathers’. I expect a woman to keep her family’s linen and clothing in good order, to feed her children, order, or herself cook dinner, this without talking about it, keeping her mind free and ordering her time so that she is able to talk of something else, and to please, at last, through her mood, as well as the charms of her sex So what would an 18th woman who wanted to write but had no expectations that a revolution would bring about major changes in her household duties do? This was the case of Hannah Mather Crocker, born in Boston in 1752, writer of several books and pamphlets, including “Observations on the Real Rights of Women” a work in which she cites Wollstonecraft amongst others. Crocker, although she had always been philosophically inclined, only began to write in earnest once her ten children had left home, remarking that this period in a woman’s life was : a fully ripe season to read, write, meditate and compose, if the body and mind are not enfeebled by infirmities. In other words, if bringing up ten children hasn’t left you a mental and physical wreck, now is the time to pursue a literary or philosophical career!

1 Comment

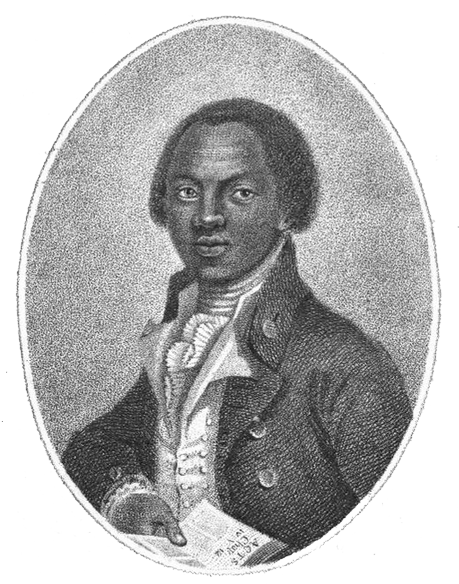

Many republican philosophers of the French Revolution, including Olympe de Gouges, Manon Roland and Sophie de Grouchy, understood the liberty they fought for as the absence of domination, rather than, as later liberal thinkers would, the absence of interference. The two are distinct in several ways, but one way in which they are is this: someone who is dominated, under the power of another, whether a slave, or a wife, or even a child, may well be free from interference at the same time = - but this does not make them free. This point is clearly illustrated by the narrative of Olaudah Equiano, 18thcentury African writer and abolitionist, who toured England in the 1780s, speaking, amongst other places, in Newington Green, Mary Wollstonecraft’s home at the time. In 1789, Equiano published his Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the Africanand Wollstonecraft reviewed it for the Analytical Review(she was on the whole enthusiastic but felt the discussion of his religious beliefs at the end was rather boring). Equiano had been sold as a child to an English navy officer, and when they were not at sea, he lived in his master’s London house, where he was taught to read and write, and even baptized by the lieutenant’s daughter. Because he was treated kindly, and accepted as one of the family by his master’s daughter, Equiano developed a sense of security, thinking of himself as something other than a slave: For though my master had not promised it to me, yet, besides the assurances I had received that he had no right to detain me, he always treated me with the greatest kindness, and reposed in me an unbounded confidence. And yet, one day, after months of fighting alongside each other, the lieutenant sold him. Equiano was told to board a barge from where he would join a ship sailing to Montserrat in the Caribbean: I made an offer to go for my books and chest of clothes, but he swore I should not move out of his sight; and if I did he would cut my throat, at the same time taking his hanger. I began, however, to collect myself; and, plucking up courage, I told him I was free, and he could not by law serve me so. But this only enraged him the more. The ship captain introduced himself as his new master, leaving no doubt, this time, as to what the relationship would be: 'Then,' said he 'you are now my slave.' I told him my master could not sell me to him, nor to any one else. 'Why,' said he,'did not your master buy you?' This is a clear example of someone who thought they were free, because they were allowed to educate themselves and work for money (even though Equiano gave his wages to his master, he seemed to have been under the illusion that it was for his upkeep, and he managed to retain enough to buy books). The lieutenant did not interfere with his efforts to better himself; he encouraged him by letting him be educated with and by his daughter. He acted kindly and generously. And yet, at a moment’s notice, with no explanation, he sold him off to a violent man, to an uncertain (but certainly miserable) fate. And even then it took young Olaudah a while to realize that he had not been, at any point, free, that his sense of freedom had been but an illusion, and that all along he had been under the power of his master, depending on his goodwill (or laxity). As soon as that good-will was exhausted, simply because the master needed money, the lack of freedom became painfully apparent.

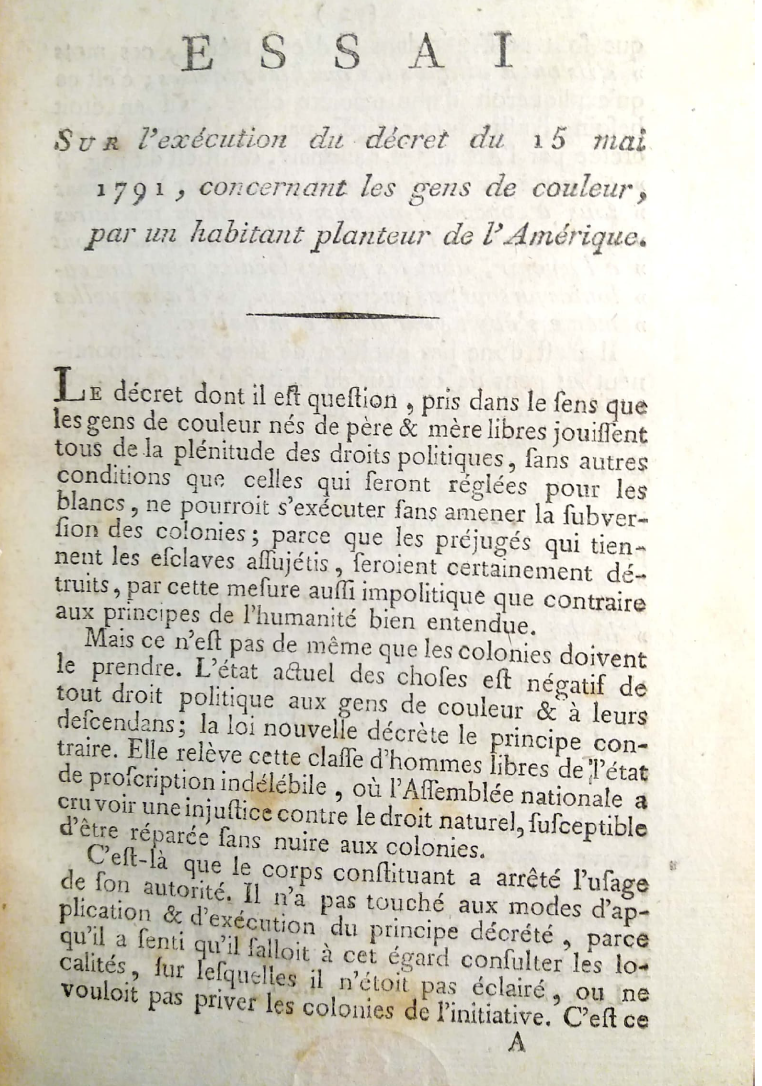

Three arguments from white colons against granting people of colour the rights of active citizenship8/15/2018 Although the Club des Amis des Noirs wanted the abolition of slavery, the question that was debated in the National Assembly in 1791 was whether free people of colour should be granted active citizenship. In 1791 white colons proposed to the National Assembly that a distinction should be established in the colonies between free people of colour and white people, introducing several classes drawn in accordance to degree of black ancestry, which was assumed to be correlated with appearance of whiteness. An edict of 1685 granted any person who had been freed from slavery the same rights as those subjects who had never been slaves in the first place. Therefore, to introduce a distinction in 1791 would be to go back on this edict. Free people of colour were people born of a free mother and father, and had at least one black ancestor. Active citizenship meant the right to vote. The proposed distinction would have given free people of colour civil rights, but not political ones. The arguments presented by white colons against granted free people of colour full rights of citizenship were of course appalling, both in their logic and their content. Here are a few examples: 1) From:Motifs de la motion faite a l’Assemblée nationale le 4 mars 1791, par M. Arthur-Dillon, Depute de la Martinique. Arthur-Dillon (1750-1794) was an English born aristocrat who inherited leadership of French regiment. Fought for American and French revolutions. Having sailed to Caribbean he met and married Louise de Girardin de Montgerald, Comtesse de la Touche. The couple had six children. Arthur-Dillon eventually came back to Paris as depute of Martinique. In a speech for the National Assembly he writes about the dangers of the opinions of the Club des Amis des Noirs. “They have no knowledge of the place and want to destroy at once political ties that only time and a long period of calm could weaken. Allowing men of colour to be represented at the Assembly would result in an immediate insurrection of the colonies against France.” This argument: ‘you don’t know what it’s like there’ was one most commonly used by white colons. 2) From: Essai sur l’execution du decret du 15 mai 1791, concernant les gens de couleur par un habitant planteur de l’Amerique. The anonymous planter argues that the decree that PoC born of free mothers and fathers should enjoy civil and political rights “will bring about the subversion of the colonies because the prejudices which keep slaves in bondage will be certainly destroyed by this act as politically flawed as it is contrary to the principles of humanity properly understood.” He goes on to explain: “The prejudices of slaves are precious; we must preserve them carefully. We can even say that each time we touch them, we will accelerate the subversion of the colonies in proportion to the gravity of the attempt against them”. And again: “They believe themselves to be bound to servitude because they are black and because they came, or their parents did from a foreign land where slavery exists. Thinking of themselves as men, as it were, or a different species, they are become familiar with the superiority of the white, in whom they see benefactors who free slaves and better the lives of those who are not white. Last, their state, made sweeter by habit, is only bitter for a few markedly bad individuals”. He also notes, more sensibly, perhaps, if only because this is an argument that can be engaged with: “There is nothing as dangerous as an excessive population of free men in a country where only slaves cultivate the earth, and which is fed mostly form outside, and whose near totality of production is not edible.” This argument was often cited, not only by colons, but by the abolitionists who recognized that this was an economic consideration worth taking into account. Olympe de Gouges responded that freed slaves would be more willing to cultivate the earth once they had a stake in it. 3) From: Réponse d’un ami des Noirs a la lettre de M.***, habitant de Saint Domingue. Paris, 16 Novembre 1791.

The author blames revolts in Saint Domingue (Haiti) on the Club des Amis des Noirs, and specific members he refers to only by their initial. He claims that the true friends of black people are ‘all men who are just and humane, all planters who work to sweeten, through their goodness, the necessary dependence of the laborious and faithful negro, and only punish the guilty negro regretfully.’ He goes on to make a most counter-revolutionary analogy: "It is possible to love the Blacks like the French love the people, who, because they have more passions than lights, think they serve the cause of liberty and equality when it only defiles itself with crime and precipitates its fall into an abyss of misery, and is nothing but the instrument of the fanatics and the factions.” The view that black people are not to be seen as human in the same way as white people are was actually shared by the National Assembly in 1791, who granted the colons that black people were like children, in a state of prolonged minority, and that the state ought to act towards them as a parent, making decisions on their behalf. (Projet d’instruction pour les colonies relativement aux Decrets des 12 et 15 ) Having interested myself in Olympe’s anti-slavery writings, and Brissot’s Club des Amis des Noirs, I was delighted to find a series of texts relating to the citizenship of ‘People of Colour’ of Saint Domingue (now Haiti) written in 1791. Why the quotation marks? Because it turns out that ‘Person of Colour’ in 1791 meant something rather different from what it does now. Specifically, it did not mean a black person. The author of the text, Julien Raimond, identifies himself as a person of colour in the text in which he argues that free men of colour ought to be granted the status of active citizens in the colonies. They deserve this status as much as the white men, he says, because like them, they are free. So first, Raimond does not ask that slaves should be granted the status of citizens, nor indeed that slavery should be abolished. Secondly Raimond argues that all men of colour, regardless of their degree of whiteness, ought to be granted the same status, as otherwise, brothers and sisters, parents and chidlren, would be turned against each other. In order to make this argument, he says that he needs to explains what he means by ‘People of Colour’ and ‘degree of whiteness’. A child issued of a white man and a black woman is a mulatto (mulatre). A child issued of a white man and a mulatre is a quarteron, or second degree. A child issued of a white man and a quarteron is a tierceron, or third degree. A child issued of a white man and a tierceron is a metis, or third degree. The colour of the skin of a metis, Raimond says, is indistinguishable from that of a white person. Any person belonging to that group is referred to as a ‘Person of Colour’. Julien Raimond himself was the son of a mulatto, Marie Bagasse, and a planter. He became a wealthy slave owner. In 1785 he moved to Paris and eventually became a member of the French National Assembly during the Revolution and helped Toussaint Louverture write the first Haitian Constitution. Raimond notes, without commenting on it, that prejudice means that couplings will always have to be of a white man with a woman of colour.

This is part of the reason why citizenship should be granted to all free people of colour, regardless of their degree of whiteness: a brother and a sister, both tierceron, will otherwise risk belonging to different classes. The sister might marry a white a man, in white man, and then her metis children will become citizens, and they will look down on their cousins who are not. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed