|

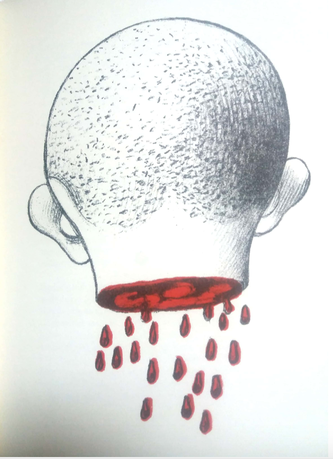

During a recent visit to the Conciergerie, I picked up a prettily bound book, entitled Note sur le supplice de la guillotine. The book contained a short essay of that title by Cabanis, five drawings by the artist Cueco, and a discussion of the moral and political philosophy of the guillotine by French philosopher Yannick Beaubatie. For the main part, Cabanis's article, written 1799 (an IV) argues against recent articles that claimed that the torment of the guillotine ought to be abolished because it cannot be proven that the guillotined do not feel pain. The articles (by members of the medical profession, Cabanis's own colleagues), cite as evidence witnesses's reports of decapitated heads moving in such a way as to suggest that they responded to the situation, and attempted to communicate. One example they cite is that of Charlotte Corday, whose decapitated head was slapped by one of Sanson's valets, after which it apparently reddened as if in shame and indignation. Cabanis answers that while he was not present at any decapitation (as he did not have the stomach for it) he was present at the testing of the machine and certifies that death must be instanteanous. He then goes on to discuss the philosophical question of where pain resides, and the medical phenomenon of bodily movement after death. At the end of the essay, Cabanis offers his moral and political reflections: the death penalty, he claims, ought to be abolished. But if it is not, the guillotine has to go. Not because it causes pain to its victim, but because it is too swift so that as a performance of a punishment it cannot serve its rightful purposes. Beaubatie takes this up in a fascinating discussion. In particular, he notes a resemblance between Cabanis' s reservations about the guillotine and Beccaria's utilitarian theory of punishment. Beaubatie notes further that Beccaria and Cabanis both frequented the Helvetius home, although two years apart. What Beaubatie does not note, however is the strong resemblance between Cabanis's thought and that of his sister in law and long term friend and collaborator Sophie de Grouchy. Cabanis's principal reason for thinking that the guillotine should not be used is not - as Beaubatie claims - that it cannot serve as an exemple or detterrent, but that it does not allow enough time for spectators to react emotionally in such a way that would help their sympathy grow. The guillotine’s work is done in less than a minute. That it did not occur to Beaubatie, in his commentary written in 2002, to look to his long term philosophical correspondent Sophie de Grouchy for influence, as well as to Beccaria (whose path with Cabanis crossed, but two years apart) is a sign of how much work has been done over the last fifteen years in recovering the works and influence of women philosophers.

1 Comment

In 1798, Sophie de Grouchy published her Letters on Sympathy. We know that she already had a draft in 1791, which she'd sent to her friend Dumont for feedback that never came. We know that the Letters were complete in 1794, and that they had a title, as Condorcet refers his daughter to them in his Testament. So why were they only published in 98? We don't know as she did not leave an account. But it's likely the answer lies either in need, opportunity or both. After the Terror, Sophie needed money, and she decided to translate Smith's Theory of Moral Sentiment. Smith was very popular, and existing translations of this text were not particularly good, so there was a clear gap in the market. This also gave her the opportunity to publish her own short text. Her Letters were after all a critique and commentary of Smith. So she appended them to the translation. Although the Letters are in fact a more like a treatise than a record of correspondence (there is in fact only one letter writer involved), each chapter is set out as a letter to someone addressed as C***, announcing the topic of discussion, linking it to the previous one, and at the end, drawing out the conclusions to be taken forward to the next chapter. C*** is also an excuse for considering objections to Grouchy's arguments, with many paragraphs starting with formulas such as "No doubt you will tell me, my Dear C***". So C*** is very much a philosophical interlocutor, the Platonic touchstone to Sophie's Socrates. So who is C***? The obvious assumption is that it is Sophie's husband, Condorcet. But there are reasons why this is probably not true. First, her husband was dead by the time the Letters were prepared for publication. Secondly, if Sophie was to record a fake dialogue with a real person then she would probably have picked someone she actually corresponded with - in 1791, when the letter were written, Sophie and her husband were not apart long enough to correspond. But there were at least two more Cs in Sophie's life, to whom she was very close, with whom she did correspond and who were still alive when the Letters were published. They were her sister Charlotte, and Condorcet's close friend, Pierre George Cabanis. Of the two, C*** cannot be Charlotte, as 'My Dear C***' in French is 'Mon Cher C***' which is masculin. So Cabanis is more likely. Cabanis, as it happens, did correspond with Sophie on topics very close to her Letters, on Physiology, a materialist science aiming to understand human beings through their bodily organs. In 1802, Cabanis published his Rapports du Physique et du Moral de l'Homme, in which he explores the relations between bodies and morality, discussing for instance, the influence of weather and digestion on mood and decision making. Prior to publishing this, he corresponded with Sophie, and had long discussions with her on the subject.

Physiology is also central to the Letters on Sympathy, as Sophy argues that our moral feelings are born out of the physiological response that ties a newborn to the person that nurses her and holds her. Cabanis and Charlotte de Grouchy became lovers during the Revolution, and in 1796, they were married. Some readers like to see a love story behind every text (in particular, texts written by women!) but in this case, we must suppose that C*** was very much an intellectual interest (and a close family friend) but not a love interest. Cabanis was by profession a doctor in medicine but did not practice. Some say that was because of his own poor health. Some say that he was in fact a spy, not a doctor. He is also reputed to have given Condorcet a dose of poison to hide in a ring. And this poison, in some accounts of Condorcet's death, is what he took to kill himself when he was captured in March 1794. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed