|

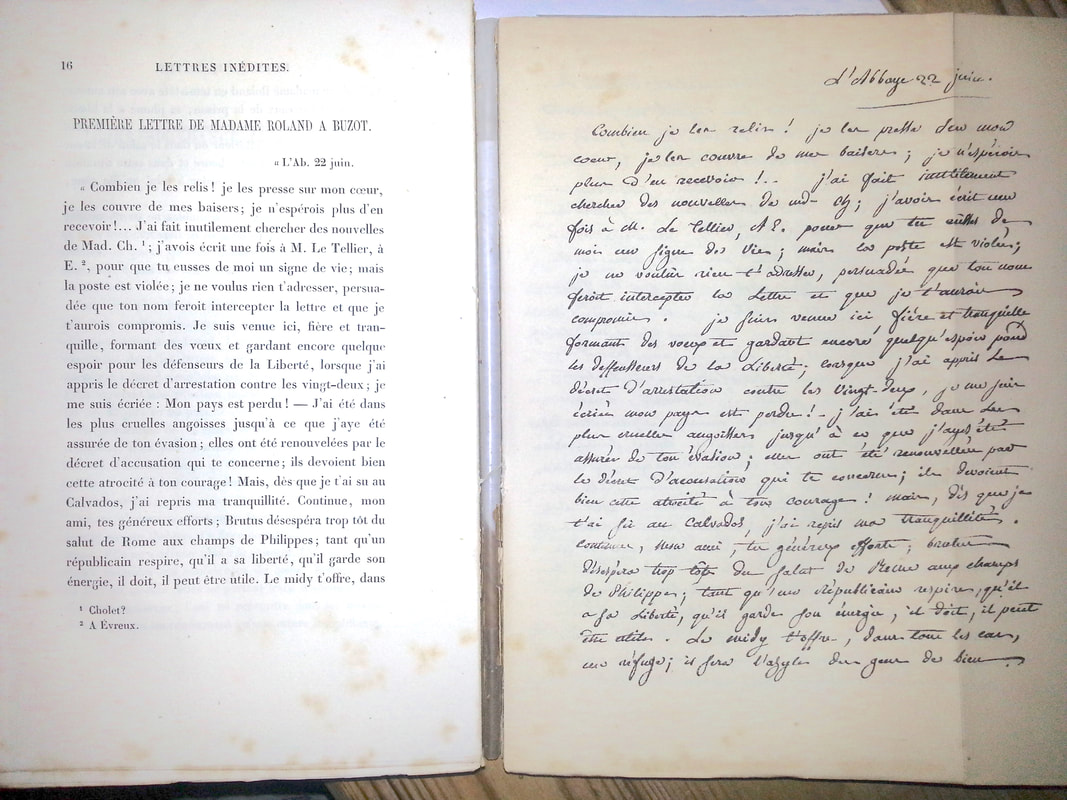

During her trial, and throughout her Memoirs, Manon Roland presented herself as a model wife to her husband. But reading through her recollections of the early days of hers and J.-M. Roland’s courtship, one is underwhelmed. Their courtship was long, their engagement business like – he was always hesitant and there is very little passion showing in Manon’s accounts. It was not a marriage of convenience: Jean-Marie Roland saw his wife as an equal in all respects, he did not attempt to dominate or curtail her, and they were partners in all their projects (except for the Memoirs which she wrote while she was in prison and he in hiding). There was a strong friendship between the two but perhaps not much more. Towards the end of her life, however, Manon did fall in love with a young Girondin (he was six years younger than her, while her husband was twenty years her senior), François Buzot. François was also married, and neither he nor Manon had any intention of breaking down their marriage. Nonetheless, Manon told Jean-Marie that she no longer loved him, and that she loved François. This is perhaps why, in the weeks before her arrest, she had planned to leave Paris. She needed some space to think. Manon's correspondence with Buzot was hidden from the public when the letters were first published, so that the image of her as a virtuous wife remained. But the truth came out in the 19thcentury: after all, all interested parties were dead. Below is a letter Manon wrote to Buzot shortly after she was imprisoned, and after the decree for the arrest of the Girondins had been issued. She had heard that Buzot, together with Jérome Pétion (whose wife was Manon 's neighbour at Sainte Pélagie, had managed to escape and that they were in the South-West of France, near Bordeaux. This is a love letter: she tells him how she covers his letters to her with kisses. But it is also a political letter: one that shows both hope and despair. She tells him that when she heard of the arrest of twenty-two Girondins, she thought France was lost. But then, she asks him to stay alive, because a republican ‘while he breathes, while he has his freedom, can and must be useful’. A few weeks after Manon’s death at the Guillotine, Buzot and Petion shot themselves in the woods of Saint Emilion. Their bodies were discovered later, eaten by wolves.

0 Comments

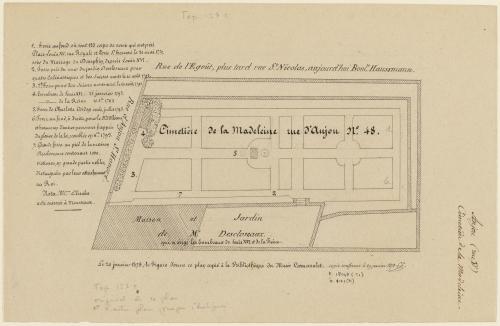

The revolutionary period, in particular the Terror, was hard on the Paris graveyards. Many people died in massacres and at the Guillotine who had to buried in the already full graveyards. When the body counts started to rise, the Parisians needed somewhere to pile up their dead. The site of the church of Sainte Madeleine, first opened in the 13thcentury was located roughly where 8 Boulevard Malherbes now stands. It had a very small cemetery and a slightly larger one was built in 1690, on land that was closer to the Faubourg Saint Honore, already a posh neighborhood. In 1720, the cure of la Madeleine sold a large tract of land to be convereted to a graveyard. The graveyard was built on a large rectangle of 45 by 19 meters surrounded by a wall. It filled up slowly at first, but in 1770 it received its first mass burial. On the occasion of the celebrations of the wedding of Louis the Dauphin and Marie-Antoinette, a show of fireworks was given to the people of Paris. This was a novelty, and more scary than exciting for many. There was a crush in the crowded streets and several hundred people died. These were buried in the Madeleine. The next large scale burial happened in August 1792, when the Paris revolutionaries, assisted by the Marseillais massacred the King’s Swiss Guards. Their mutilated bodies were thrown into the Fosse Commune at the Madeleine. By then it was summer, and the smell in the neighborhood became unbearable – someone reported it at the assembly, but it was decided that the risk of false rumours of a plague epidemic was too great if a fuss was made, and the subject was dropped. The rich inhabitants of the quartier would just have to put up with it. The location of the Madeleine was also very convenient for transporting bodies from the Place du Carousel and Place de la Revolution – the guillotine’s first two locations. Légende - Au recto, à gauche sur l'image, à l'encre, inscriptions correspondant à la numérotation de l'image : "1. Fosse au fond où sont 133 corps de ceux qui ont péri / Place Louis XV, rue Royale et Porte St. Honoré le 31 mai 1770, / soir du Mariage du Dauphin, depuis Louis XVI." ; "2. Fosse près du mur du jardin Descloseaux pour / quatre Ecclésisatiques et 500 Suisses morts le 10 août 1792." ; "3. 2e. Fosse pour 500 Suisses morts aussi le 10 août 1792" ; "4. Tombeau de Louis XVI. 21 janvier 1793. / -id- de la Reine 16 8bre 1793" ; "5. Fosse de Charlotte Corday seule, juillet 1793." ; "Fosse au fond, à droite, pour le Dc. d'Orléans / et beaucoup d'autres personnes frappées / du glaive de la loi ; comblée en Xbre. 1793." ; "7. Grande fosse au pied de la maison / Descloseaux contenant 1000. / victimes, en grande partie nobles, / distinguées par leur attachement / au Roi. / Nota. Mme. Elisabet / a été enterrée à Mousseaux.". Date et signature - Au recto, en bas à droite, à l'encre brune : "copie conforme le 29 janvier 1878 LL". - From the Musée Carnavalet. Eventually, in March 1794, the Madeleine was closed and the next victims of the Guillotine were buried elsewhere. But before then, more famous bodies were entered there, including the King and the Queen, many of their supporters and family members, Charlotte Corday – who benefitted from a single occupancy plot, the twenty-two Girondins (including Brissot) who died on 31 October 1793, and of course Manon Roland and Olympe de Gouges.

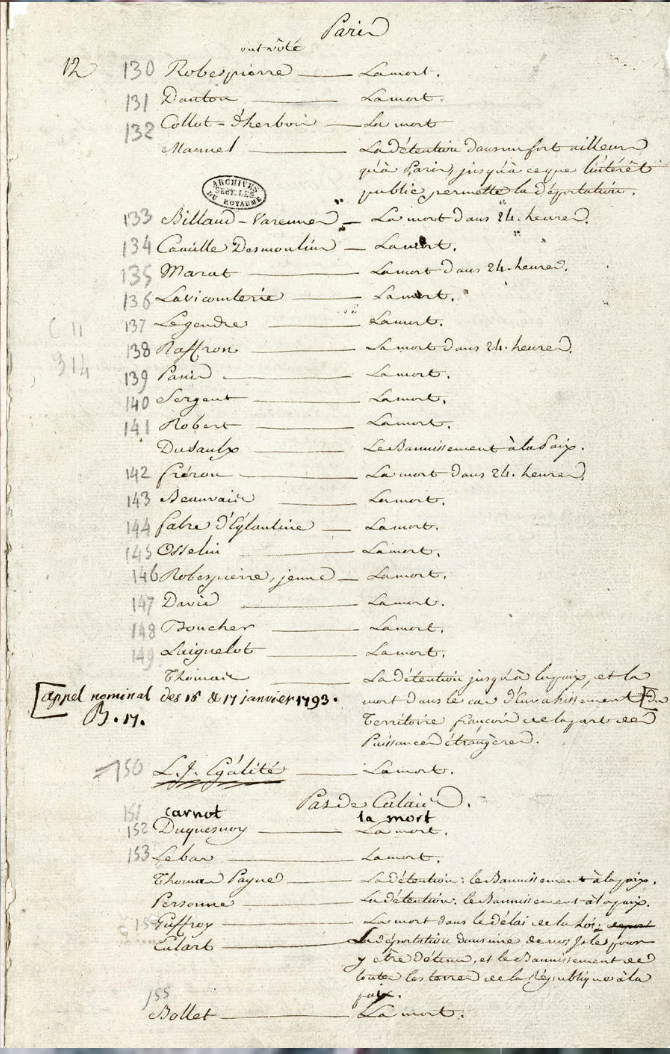

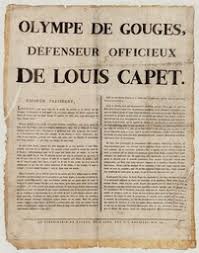

During the restoration, Louis XVIII built a chapel to the memory of his brother and sister in law. Small chapels were added later to commemorate the other victims of the Revolution. On 15 January 1793, Louis Capet, previously King of France, is found guilty by an overwhelming majority of the 749 deputies. Two days later, the deputies are asked to vote for a penalty. 346 vote for the death penalty. Others, including Thomas Paine, who had been offered honorary French citizenship, vote for exile, or for imprisonement. . One citizen, who had not voted, argued against the death penalty. Olympe de Gouges started by offering herself as Louis’s unofficial advocate on 16 December, arguing at first that while as a King, he had done harm to the people of France by his very existence, once Royalty had been abolished, he was no longer guilty. As king, I believe Louis to be in the wrong, but take away this proscribed title and he ceases to be guilty, in the eyes of the republic. This proposal, written as a letter to the Convention, was then printed as a placard and distributed throughout Paris. The Convention disregarded the letter. Sèze was made Louis’ advocate, and the argument that Gouges put forward was not taken into consideraton. Louis Capet, stripped of his title, was still tried for high treason, i.e. for actions he had performed while he was still King of France. Olympe did not stop at this. On 18 January, after the King had been found guilty, but before his death had been voted, she put up another placard addressed to the Convention and to the people of Paris, entitled “Decree of Death against Louis Capet, presented by Olympe de Gouges.” In this piece she also attempted to dispel the mistaken impression that she was in fact a royalist. Louis dead will still enslave the Universe. Louis alive will break the chains of the Universe by smashing the sceptres of his equals. If they resist? Well! Let a noble despair immortalize us. It has been said, with reason, that our situation is neither like that of the English nor the Romans. I have a great example to offer posterity; here it is: Louis' son is innocent, but he could be a pretender to the crown and I would like to deny him all pretension. Therefore I would like Louis, his wife, his children and all his family to be chained in a carriage and driven into the heart of our armies, between the enemy fire and our own artillery. (http://www.olympedegouges.eu/decree_of_death.php) Here Gouges is appealing to a well-known fact about the workings of royalism: a King cannot die. The holder of the title may die, but the title passes automatically to the next contender, without, even, the necessity of sacrament. The immortality of the king was such an important precept that a Chancelier, when a monarch died, could not wear mourning. Bossuet captured the phenomenon thus in his Mirror for Kings: Letting Louis live, she would go on to argue in her final published piece, 'Les trois urnes'. would have made it clear that he was no longer a threat to the republic - as no one individual is. To execute him is both to betray a certain lack of confidence in whether the people have truly succeeded in aboloshing the monarchy, and perpetuate that doubt, as after Louis's death, his title is transferred to his descendent.

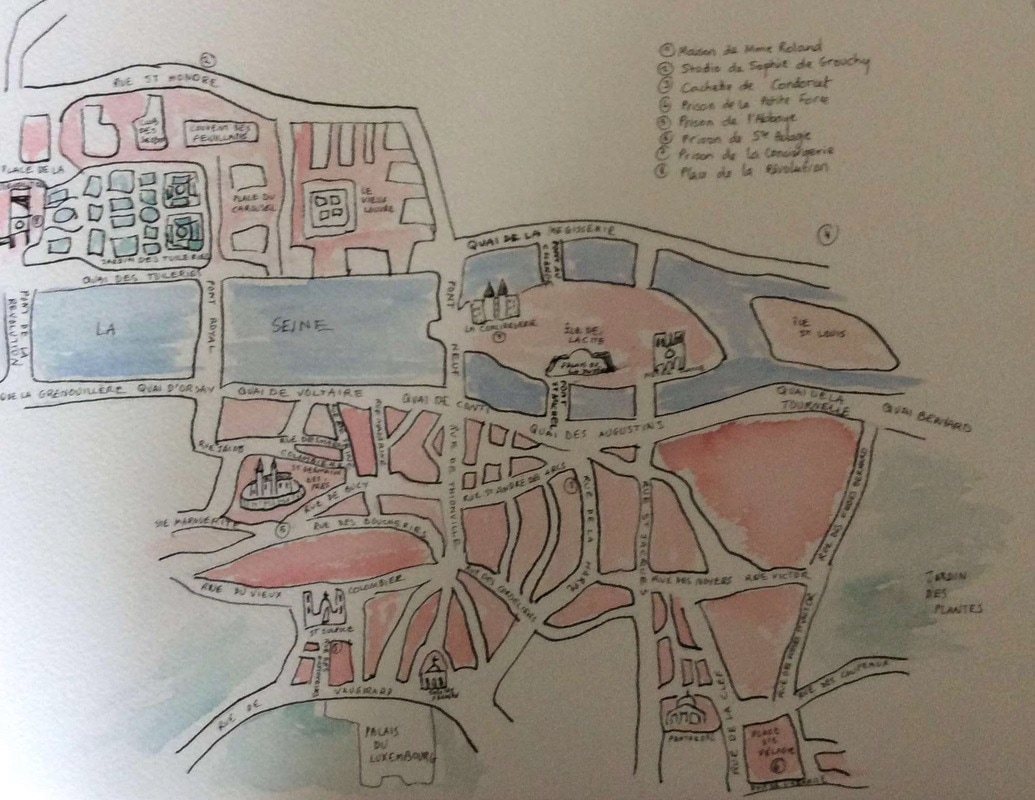

On 30 December last year, I took a walk in Paris with my daughter and her friend, to identify some of the places where Olympe de Gouges, Manon Roland and Sophie de Grouchy had lived or worked. We found very few actual buildings as many were destroyed when Paris was redesigned in the 19th century. We did find, however, the building on the Faubourg St Honore where Sophie de Grouchy set up her studio in 1793, when her husband, Condorcet was in hiding on the Rue des Fossoyeurs (we also found this building). Someone was entering the St Honore building, so we decided to sneak in behind them. We looked around, finding little of interest, Were we expecting discarded paint brushes or watercolour stains? But we were very pleased to have gotten that far. There was a small courtyard, a staircase, and a door under the stairs (locked, of course) that may well have led to the studio. Of course when it came to coming out again the door was not only locked, but the electrical mechanism for opening it was stuck! We pressed and pressed that button to no avail for a whole five minutes until it eventually did work.

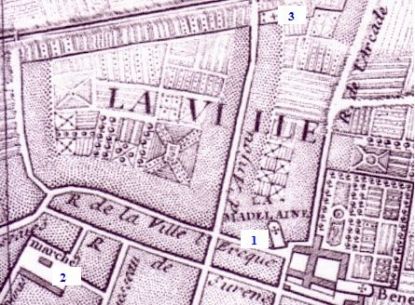

Gouges, Roland and Grouchy all did a lot of walking around Paris, between 1789 and 1793. We tried to retrace their steps, sticking to the streets that dated from that period, and avoiding the new boulevards when we could. But come five o'clock we went for the metro (it was winter, after all!). When I came home I tried to replicate the map of the streets they would have walked, based on maps drawn around that time. The image above is a (poor) photograph of the map, with the places we visited listed at the top. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed