|

In September 1787, Manon Roland was staying at Le Clos, the Roland family home in the countryside. She and her husband were about to take possession of the house, and she was beginning to renovate it, while Roland was working nearby in Lyon. Eudora, their daughter, was six years old. It’s very cold here, but our rooms are comfortable even without a fire, and one could easily spend the winter here. All that is missing are chairs, which will come on Friday, weather permitting, and the top of the book case, which would not fit on the first cartload. Our child is quite well behaved with me. I have established a schedule, and I think this is an excellent method. We wake up together at six: we get dressed, read catechism and do some needle work, all this together until eight. Then breakfast together, great happiness and play till half past nine. Then we go back upstairs and I write, while the child sews or knits till half-past eleven. Then play for her, but indoors, till twelve. At twelve, she chooses a book to read, then music lesson. Lunch at one. Play until three. Upstairs again then work or reading till five (keeping the readings short). A collation at five, then play till six, or later if we go out; otherwise we go in and she has another music lesson. She dines and goes to bed between seven and eight. I dine after eight and go to bed an hour later.

1 Comment

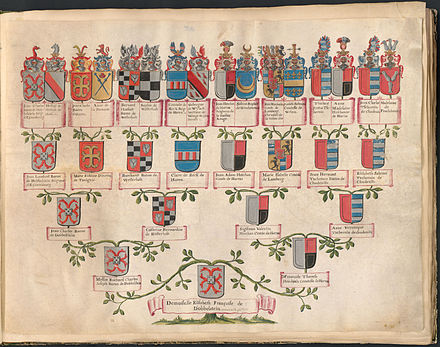

When Sophie de Grouchy was young, no tutor was assigned to her. But she benefitted from her mother's instruction, a woman known for her intellect, culture and generosity. And she was allowed to participate in her younger brothers' lessons. She did so well at this that when their tutor was sick, she took over their Greek and Latin instruction. At the age of 18, she was sent to a finishing school in Normandy, at Neuville-les-Dames, near Macon, a secular convent for ladies. She received the title of Chanoinesse, and was addressed as Madame. In order to gain admission, one had to pay a substantial fee and maintenance amounting to 9000 pounds per year, but also provide proof of lineage: 9 generations on the father's side and 3 on the mother's. The convent was not ostentatiously religious. Pupils studied Latin and modern languages, and worked on their accomplishments. They hosted parties, the purpose of which was to find husbands of the right sort. In an environment that was religious and socially privileged, she became an atheist and socially aware. She discovered Voltaire and Rousseau, she read and translated Tasso's Jerusalem, and an unnamed work by Young (probably his Tour of Ireland). Her aunt, visiting her, worried about her health - her eyes were puffy every night and ached so that she feared it might be a form of gout. And yet Sophie kept on with her work.

The building Sophie lived in is long gone. But Neuville now has an Allee Sophie de Grouchy, on which stands an elementary school, l'école Condorcet. There are many schools named after Condorcet in France, but if this one is named after the Marquise, not the Marquis, then it is, as far as I know, unique. As most Parisian children of the times were, Manon was sent to spend her first two years in the home of a wet-nurse, in the country side. Perhaps Paris was not a great place to bring up a baby, and Marie-Jeanne’s parents had already lost several children, so they were bound to be more careful. Fresh air, a nurse who has nothing to do but fuss over her, this would keep her alive, make her healthy and strong. And whether or not from the effect of her residence in those first two years, Manon, as her mother called her, was healthy and strong, and would no doubt have lived well beyond the age of 38, had she not been guillotined. When she came back it was not to the Ile de la Cite, but on the other side of the Pont Neuf, Quai de l’Horloge. Young Manon had the run of her father’s library – not a large one – and on certain days, she has the run of the town. She has tutors – no expense was to be spared in the clever child’s education. She knew her catechism by heart but was not convinced by what she learned. On Sundays, she hid a favourite book in the cover of her bible: Plutarch’s parallel lives, translated into elegant French by Anne Dacier. She embraced republicanism, admiring the values and virtues of the Roman leaders she read about. She began to wish she had been born Roman, or above all a man, so she could act on her convictions. But soon even Plutarch was no longer enough. She wanted to learn more and her tutors – music, languages – could not teach her enough.

When Manon 11 an apprentice of her father assaulted. The experience shocked her deeply and she sought refuge in religion. Manon begged her parents to be allowed to continue her studies at a convent school on the Ile de la Cite. But at the Convent of the Augustines, Manon, a precocious child, turned out to be difficult to teach, as she knew more already than the kindly nuns who’d agreed to take her on. She stayed a year, and made lifelong friends there, two of whom, the Cannet sisters, became her correspondents and later introduced her to her husband to be. In the 1750s, when Marie Gouze, as she was then called, was of the age to learn how to read, the education of French children was under the control of the catholic church. There were few options: you could be educated at home, privately, by a parent or a tutor, or you could be sent to school. Boys who were not particularly rich, might do better at school than at home. Maximilien Robespierre, for instance, won a scholarship to leave his native Arras and study at the Lycee Louis le Grand, in Paris. But there were no equivalent schools for girls, so unless they could be educated at home, working perhaps with their father, as Anne Dacier had done, or with their brothers' tutors, as Sophie de Grouchy did, girls were sent to convents, or to the Ursulines' day Schools.

The Ursulines school at Montauban had been started in 1682, by six Ursuline sisters from Toulouse. Their school still stands - it has been expanded, and they now have a very modern looking building. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed