|

In the winter 1776, Manon Phlippon was 22. She lived alone with her father in Paris on the Quai de l'Horloge, - she had not yet met her husband, Jean-Marie Roland - and she spent much of her time writing in her room, letters or essays in political philosophy. Late on Christmas eve, as the revellers were going home, she wrote a letter to her close friends, Henriette and Sophie Cannet.

0 Comments

25 December 1776, 1am

As you can see, I am not gone to the midnight mass. I would have gone, as I think it is important to set an example even when one doesn't want to do it for oneself. But the weather is frightful, my father did not think it a good time to be devout, so without a fuss we stayed home. You might find it strange that I should write always at the first hour. Let me tell you a something of my daily y life which will give you insight into how I spend my time. I never get up, this time of year, before nine. I spend my morning with the housework. In the afternoon, I do needlework and I dream, building everything I fancy in my mind, poems, arguments, projects, etc. In the evening I normally read till dinner time, which is uncertain because it depends on when the master comes home. He is out at all times exept meal times, without telling me, or caring for any of his affairs, and too often leaves me to deal with those who come to do business with him. He usually gets home at half past nine, but sometimes ten or later. Supper is soon over, since when there are few dishes, one eats fast and there is no conversation no feast can last long. In between dishes, I always attempt conversation but my attempts are foiled by his careless replies. I am always trying to hold a thread; but though I do my best, it is always in vain. Eventually time passes and it is eleven. My father throws himself in his bed, and I go to my room, where I write two or three. In May 1792, before Mary Wollstonecraft set out for Paris, where she was to act as a war journalist for her publisher Johnson, a French translation of her Vindication of the Rights of Woman came out. Before traveling she wrote to her sister: "I shall be introduced to many people, my book has been translated and praised in some popular prints". So who was the author of this translation that was so favorably reviewed?

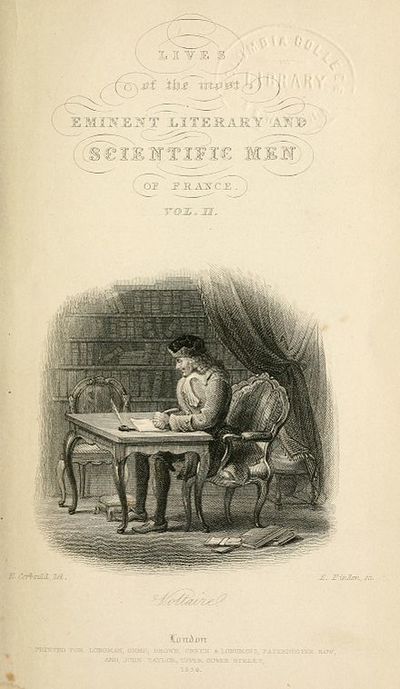

La Défense des Droits des Femmes was translated anonymously. Isabelle Bour suggested that it might have been translated by a member of the Girondin circle. This is quite plausible as we know that the Girondins did defend to some extent women's rights. Condorcet published an article arguing that women should be given equal political rights to men in 1791, so that Wollstonecraft's book would have struck him as important and topical. So who was close enough to Condorcet to share his views on women and citizenship, knew enough English to read the Vindication and was an experienced translator? Sophie de Grouchy, of course. We have already speculated as to whether she had read anything by Wollstonecraft, and whether she could have met her. This is another possibility to add to the mix. In 1839 and 1840, Mary Shelley published her two-volume Lives of the Most Eminent Literary and Scientific Men of France. This was part of ten volumes of biography published in the 133 volumes series of Dionysius Lardner: Cabinet Cyclopaedia (1829–46) The series was designed to educate the Middle classes. In her volumes on famous French men, out of 15 lives, 3 were women: Madame de Sevigne, Madame de Stael and Madame Roland. This may seem a low percentage for the daughter of Mary Wollstonecraft. And indeed, there were women writing biographies of famous women, for instance, her mother's friend Mary Hays, who wrote Female Biography: or Memoirs of Illustrious and Celebrated Women of All Ages and Countries. But Shelley, one must remember is a history book designed for readers of both sexes, in which she includes women. So in a sense her inclusion of these three women alongside 12 well known and respected men (Voltaire, Rabelais, Fenelon, Pascal, Mirabeau, Racine, Corneille, Moliere, Boileau, Rochefoucault, Rousseau and Condorcet) is more daring than a book solely about women, which may not be taken seriously at all by male readers. So what did Shelley say about Manon? Disappointingly, she focuses on her virtues as a wife and mother: She was her husband's friend, companion, amanuensis; fearful of the temptations of the world, she gave herself up to labour; she soon became absolutely necessary to him at every moment, and in all the incidents of his life; her servitude was thus sealed; now and then it caused a sigh; but the holy sense of duty reconciled her to every inconvenience. She was probably not aware, because it was not revealed until the early 20th century, that Roland had all but left her husband, before she went to prison, and that she was in love with their friend and colleague Buzot. Both men committed suicide shortly after her death. What I found more interesting, and which again may have been a function of how many of Roland's papers had been released at the time Shelley was writing, is her representation fo Roland as an activist, rather than a writer. Her fame rests even on higher and noble grounds than that of those who toil with brain for the instruction of their fellow creatures. She acted. What she wrote is more the emanation of the active principle, which, pent in a prison, betook itself to the only implement, the pen, left to wield, than an exertion of the reflective portion of the mind. Shelley might well be forgiven for thinking that Roland was a doer more than she was a thinker, if she was acquainted mostly with the prison memoirs, and with Roland’s reputation as a ring-leader, or egeria of the Girondists. The picture, however, is far from accurate. Manon Roland was a writer – producing hundreds of well crafted letters in which she presents philosophical as well as political reflections, writing essays and travel journals which she would not publish in her own name. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed