|

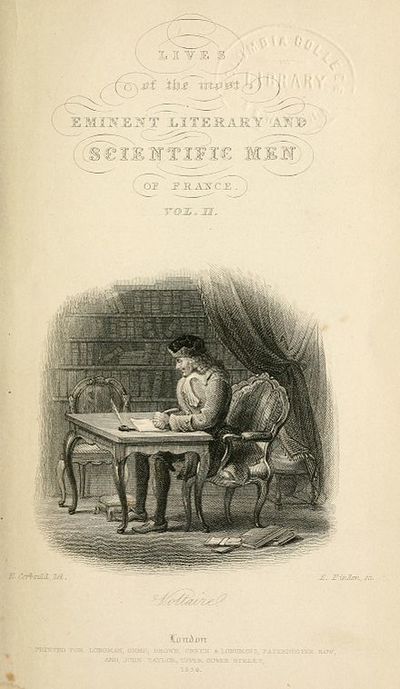

In 1839 and 1840, Mary Shelley published her two-volume Lives of the Most Eminent Literary and Scientific Men of France. This was part of ten volumes of biography published in the 133 volumes series of Dionysius Lardner: Cabinet Cyclopaedia (1829–46) The series was designed to educate the Middle classes. In her volumes on famous French men, out of 15 lives, 3 were women: Madame de Sevigne, Madame de Stael and Madame Roland. This may seem a low percentage for the daughter of Mary Wollstonecraft. And indeed, there were women writing biographies of famous women, for instance, her mother's friend Mary Hays, who wrote Female Biography: or Memoirs of Illustrious and Celebrated Women of All Ages and Countries. But Shelley, one must remember is a history book designed for readers of both sexes, in which she includes women. So in a sense her inclusion of these three women alongside 12 well known and respected men (Voltaire, Rabelais, Fenelon, Pascal, Mirabeau, Racine, Corneille, Moliere, Boileau, Rochefoucault, Rousseau and Condorcet) is more daring than a book solely about women, which may not be taken seriously at all by male readers. So what did Shelley say about Manon? Disappointingly, she focuses on her virtues as a wife and mother: She was her husband's friend, companion, amanuensis; fearful of the temptations of the world, she gave herself up to labour; she soon became absolutely necessary to him at every moment, and in all the incidents of his life; her servitude was thus sealed; now and then it caused a sigh; but the holy sense of duty reconciled her to every inconvenience. She was probably not aware, because it was not revealed until the early 20th century, that Roland had all but left her husband, before she went to prison, and that she was in love with their friend and colleague Buzot. Both men committed suicide shortly after her death. What I found more interesting, and which again may have been a function of how many of Roland's papers had been released at the time Shelley was writing, is her representation fo Roland as an activist, rather than a writer. Her fame rests even on higher and noble grounds than that of those who toil with brain for the instruction of their fellow creatures. She acted. What she wrote is more the emanation of the active principle, which, pent in a prison, betook itself to the only implement, the pen, left to wield, than an exertion of the reflective portion of the mind. Shelley might well be forgiven for thinking that Roland was a doer more than she was a thinker, if she was acquainted mostly with the prison memoirs, and with Roland’s reputation as a ring-leader, or egeria of the Girondists. The picture, however, is far from accurate. Manon Roland was a writer – producing hundreds of well crafted letters in which she presents philosophical as well as political reflections, writing essays and travel journals which she would not publish in her own name.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed