|

A lot of skepticism about the interest of women philosophers of the French Revolution is due to the belief that the arguments of women involved in the Revolution came from a place of great privilege, and that they did nothing to address the plight of women who were poor, or even enslaved.

This leads critiques to nod gently and say, perhaps, that this first effort towards women's emancipation was indeed admirable, and helped set the tone for later efforts, but that it isn't quite what we're looking for. Similar points are often made about Mary Wollstonecraft – her feminism was too bourgeois, and it did not address the pressing concerns of working class women (despite the fact that half of her final book, Maria, or the Wrongs of Woman, concerns the plight of working class women). Some things need to be cleared up here. Out of the three women I research, only one, Sophie de Grouchy, was an aristocrat. Olympe de Gouges, (Marie Gouzes by birth) was the illegitimate daughter of an aristocrat. But the father who brought her up was a butcher, and her mother died in poverty. She was educated badly, like a country girl, and only became cultured and literate because she worked hard on teaching herself as a young adult. Manon Roland's father was an artisan, and by the time she was a teenager, he was a failing alcoholic of an artisan. His people had been wine sellers. Her maternal aunt was a servant in the household of a rich woman. Manon was brought up in Paris, and her education received more care because she was a bright, and an only child. But she describes running errands as a child in the streets by the Ile de la Cité, mixing with the common people and not looking or feeling any different from them. Manon married into minor nobility (Jean-Marie Roland was the younger son of a small aristocratic family, but had to earn a living for himself by working as an inspector of textile manufactures). So why do people assume that these women must have been aristocrats? Perhaps because they don't think it would have been possible for women who were not already privileged to stand out from the crowds, to educate themselves, and to make their voices heard. This is something that men can do – women must conform and stay with their family. Another side of the prejudice is the enduring belief that as privileged women, they would not have been in a position to understand or sympathize with women who were not privileged. Again this is an objection that specifically applies to women. No-one complains of Condorcet that he was an aristocrat. No one suggests that as such his political writings are outdated, or unhelpful for the common people. So I'm just setting the record straight here. The women of the French Revolution were not all aristocrats, and even when they were, they were just as capable of being informed about the poor and the disadvantaged as their male counterparts were. Of course, privilege remained an obstacle to full understanding, but not to the extent to which we should now reject their writings. So keep reading!

0 Comments

Some of you may have noticed, reading through these posts, that I usually drop the particle when I write about Grouchy, or Gouges. This is why:

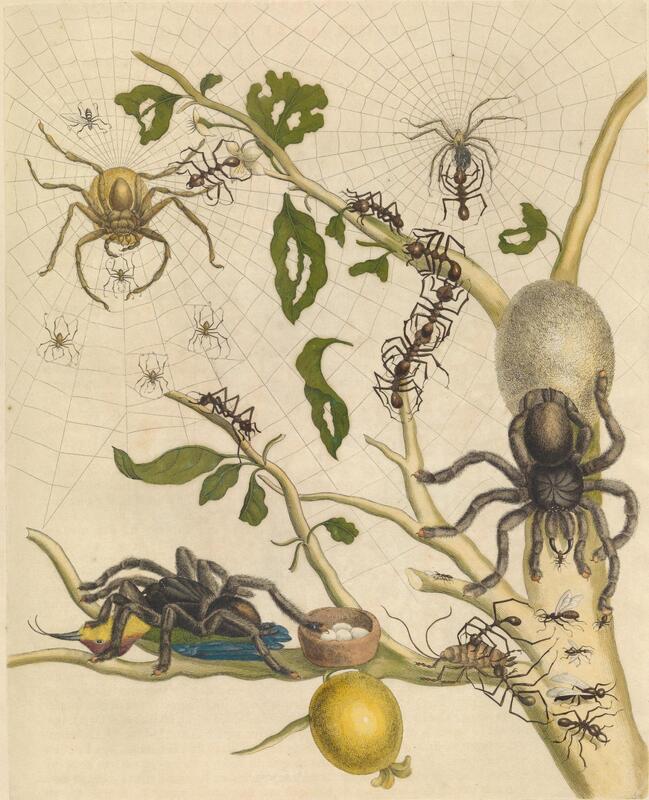

French aristocratic names often contain a particle, 'de', 'du', des' or 'd''. This usually indicates the physical place their ancestors were given to lord over. For instance, the castle Sophie de Grouchy purchased for her daughter was called 'Le Bignon-Mirabeau' and had originally belonged to the family of the famous politician, Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, Comte de Mirabeau. The castle where Sophie de Grouchy was born does not bear her family's name, but there is a village, nearby, which does. Some families used a particle without being members of the aristocracy. The leader of the terror was Maximilien de Robespierre, despite his thoroughly bourgeois origins. Some individuals simply took up the particle when they wanted to mix with the nobility. Marie Gouze, for instance, became first Marie Aubry, when she married, and upon her arrival in Paris, she adopted her mother's first name, changed the spelling of her family name, and added the particle, thus becoming Olimpe de Gouges. Note that while we write her name as Olympe, she signed herself Olimpe. Also, the change from Gouzes to Gouges is probably nothing more than an alternate spelling. One issue that non-francophone readers encounter is what to do with the particle when naming someone who used it. The good thing is that there are rules about this so you need not flounder. Another good thing is that most names have been used accurately for generations, and that it's harder to make mistakes. No-one writes about 'de Condorcet' or the 'Marquis_Condorcet'. The correct usage is to drop the particle when only the last name is used, and to keep it when the last name is preceded with a first name or title. So we say Mirabeau, but the Comte de Mirabeau. Of course it's more complicated than that – more later. It's great that we don't make mistakes when naming people we are familiar with. But very often, that will be mostly men. When an Anglophone academic wants to talk about a particled woman of the past, mistakes will happen: de Beauvoir, anyone? So here is a little primer, with examples of women's names, to help you find the correct appellation for your favorite philosophers. (See this link for a full account in French ) So: when should you use the particle? 1) Always if the last name is precede by a title or first name: Madame de Sévigné, Simone de Beauvoir (but note that when only their last names are used, they become Sévigné and Beauvoir). When the last name is used by itself: 2) No, if the last name starts with a consonant, or an aspirate h, and has more than one pronounced syllable: Grouchy, Pizan (although some Medievalists would suggest we call Christine de Pizan, 'Christine' others argue we should use her last name) . 3) No, if the name starts with an article that does not change with the particle. De+L', or De+La The epicurean philosopher Ninon de Lenclos, was also known as L'Enclos. 4) Yes, if the name starts with an article that does change with the particle. De+Le = Du, De+Les = Des. So if one's nobility belonged to a place linked to a little castle, such as was the case for Emilie Du Châtelet's husband, then the name would be Du Châtelet. 5) Yes, if the name has one pronounced syllable (with the exception of a few famous people who became known by their last names only, such as Sade). Madame De Staël, because her name is pronounced as two vowels, is Staël. But her great niece, Louise de Broglie would have been De Broglie because 'Broglie' is pronounced 'Breuil'. 'Gouges should have been De Gouges, expect that as her particle was of dubious origins, she was also simply Gouges. 6) Yes, if the last name starts with a vowel or a non-aspirate h: And sometimes, as is the case for Anne Dacier, who translated Homer into French, the particle becomes part of the name. I'm hoping you're not more confused than when you started! As always in French, there are exceptions, and as often in French, it's hard to find out what they are (And of course, it's all different for particles in other languages). As any woman who has come across, well, men, knows, sexism is very often justified by spurious appeals to science, whether it is biology, evolutionary theory, brain science, or in a more puzzling twist, mathematics ('It's maths, deal with it!' says random man on twitter). So it might be fun to know that, in the late 18thcentury, one woman sought to debunk sexism with an appeal to the study of the natural world. Here are Olympe's words from The Rights of Woman: Reconsider animals, consult the elements, study plants, finally, cast an eye over all the variations of all living organisms; yield to the evidence that I have given you: search, excavate and discover, if you can, sexual characteristics in the workings of nature: everywhere you will find them intermingled, everywhere cooperating harmoniously within this immortal masterpiece. This is perhaps not entirely accurate, but it's quite a lot better than the pseudo science that is continuously peddled at us via social media! My one criticism is that she might have reminded her readership of a number of species that don't quite fit that model of collaboration between the sexes. I'm thinking of the spider and the praying mantis.

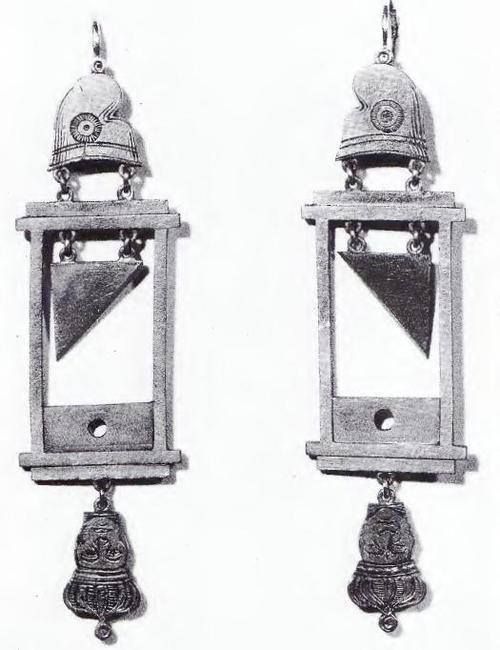

We are all familiar with the red phrygian cap with its tricolor 'cocarde' worn during the revolution. But the Revolutionary French, were full of fashion ideas. On the side of the revolution, accessories commemorated heroes, such as a ring with Marat's effigy, or events such as the fall of the Bastille painted on a fan. And in worse taste, perhaps, there were guillotine earrings, with a little falling head below the blade. On the side of those whose head might fall, there were also some interesting fashion choices. The short haircut 'à la Titus' or 'à la victime' is said to have been a snub to Sanson, who would cut his victim's hair before taking them to the guillotine. And poor taste was not only on the side of the revolution as some aristocratic women reputedly wore a red ribbon around their necks at parties… I found these images on two websites: http://histoire-du-costume.blogspot.com/2014/05/les-modes-au-temps-de-la-revolution.html and

https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2018/04/06/the-bloody-family-history-of-the-guillotine/?utm_medium=Social&utm_source=Pinterest With thanks to @prgodbarebones for pointing the guillotine earrings (!) my direction. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed