|

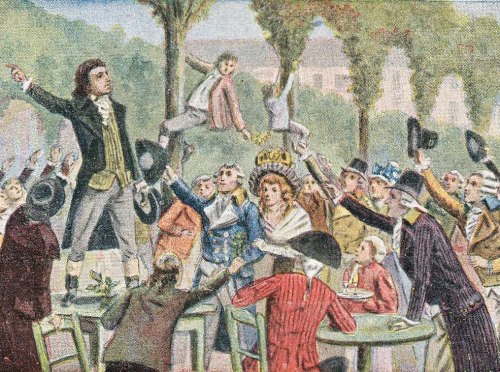

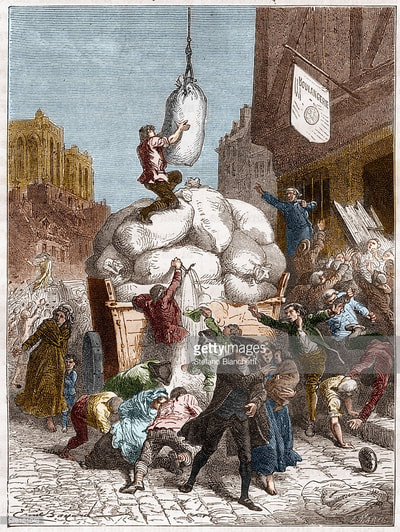

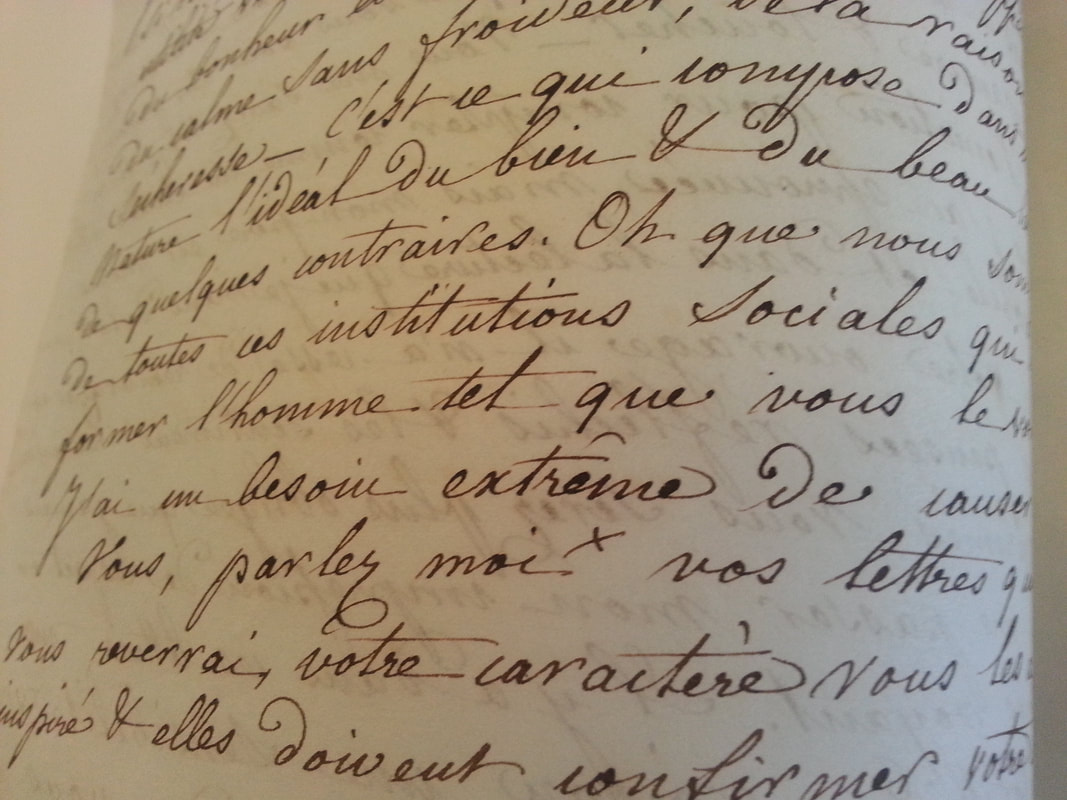

Although Madame de Stael is well known, as a historical figure and a writer, she remains very much in the background of the research I have conducted so far on the women of the French Revolution. I mentioned Roland's quip about her salon in my last post. This is as close as the two women got. Stael and Gouges never met, and although she and Grouchy moved in similar aristocratic and international circles, they were certainly not friends. Germaine de Stael was the daughter of Jacques Necker, a Swiss banker appointed by Louis XVI as finance minister in 1777. Necker held this post until 1781, when he was dismissed for having hidden the debts of France in his reports. He was recalled briefly in 1788, but dismissed again on 12 July 1789. Camilles Desmoulins, in the famous speech rousing the French people to revolt, invoked the King's treacherous treatment of Necker. Necker comes across as something of a quiet hero of the revolution, a man who did his best to resist the decadence of the French regime and serve the people. This is certainly how his daughter saw him. However, to see him as such we must leave out the story of how he became minister in the first instance. In 1776, Turgot was minister of finances, and Condorcet, director of the mint, his right hand. This was a difficult period for the French economy, marred by the flour wars, the rising price of grain which resulted in famines, and the ensuing revolts. Turgot attempted to deal with the crisis by getting rid of a number of regulations (including pricing) which had a throttling effect on the production of bread. But before he could succeed (or fail) he was dismissed and replaced by Necker. People in Turgot and Condorcet's circle believed that Necker had had a hand in his dismissal, privately misrepresenting to the King what Turgot was doing. Condorcet, when Turgot was dismissed, did not want to continue in his position. But the King ordered him to stay. This background of political squabbling may explain why Grouchy and Stael never became friends. Each was loyal to her husband or father. The rift grew bigger when the Condorcet's close friend and ally, Mirabeau took over from Necker in the heart of the French people. Necker left France, and after 1789, had no role to play in revolution. Stael fled Paris in 1792, after the September massacres, and took her salon to her chateau in Switzerland. When Napoleon came into power, he took an instant dislike to her, and she had to exile herself again. As powerful figures in French literary circles, however, Stael and Grouchy could not ignore each other. And when Grouchy's Letters on Sympathy came out in 1798, Stael wrote to her, admitting that she envied both her style and the depth of her analysis. It is not clear whether Sophie de Grouchy took the homage seriously.

Wilhelm von Humboldt, who visited Sophie in 1799 reported the letter in his Journal Parisien. "She showed me a letter which Madame de Stael had written about her book to which she gave exaggerated praise"

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed