|

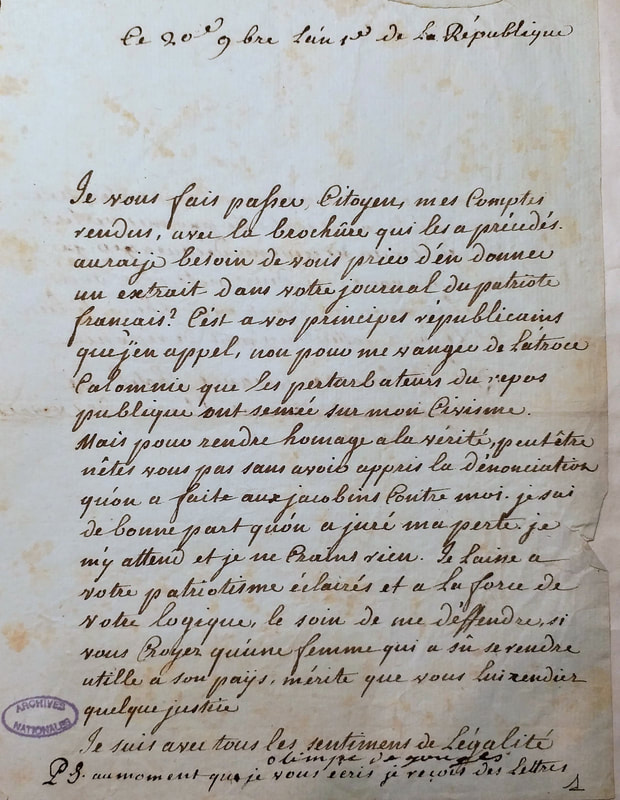

On 20thNovember 1792, Olympe de Gouges wrote to Jacques Pierre Brissot, editor of Le Patriote Francais, sending him a set of documents and asking that he should extract them in his paper. She had been denounced at the Jacobins club and feared for her safety. In the PS, she says that she has also received threatening letters and would like to set up a meeting with Brissot to discuss her situation. Gouges had in fact been denounced at the Jacobins by Leonard Bourdon, for having written against the Jacobins's actions leading to the massacres of 10 August and 2 September 1792. The Jacobins, she claimed, especially Marat and Robespierre, were entirely responsible for inciting popular violence. Interestingly, Manon Roland had blamed Danton for the same thing. But from inside the Government, Manon knew, or suspected, that it was Danton who'd ordered the signal to start the massacre, while Olympe, as a public writer and philosopher, knew that it was the speeches and writings of Marat and Robespierre that had prepared the people to react to that signal. The two documents that Olympe sent Brissot can be found on Clarissa Palmer's excellent site : Court correspondence. A principled report and my last words to my dear friends, by Olympe Degouges [sic], to the National Convention and to the People. On a denunciation made to the Jacobins, against her patriotism, by Monsieur Bourdon Prognostic of Maximilien Robespierre, by an Amphibious Animal published 5 November 1792, in which she attacks Robespierre and Marat for inciting the people to violence on August 10 and September 2. Below is a translation of the letter to Brissot and a photograph of the actual letter taken at the Archives Nationale on 5 June 2019 (446AP/7-18) Note that the letter and the signature are in different hands, as Gouges was using a secretary. Note also that she signs herself 'Olimpe', not 'Olympe'. 20 November, year 1 of the Republic

0 Comments

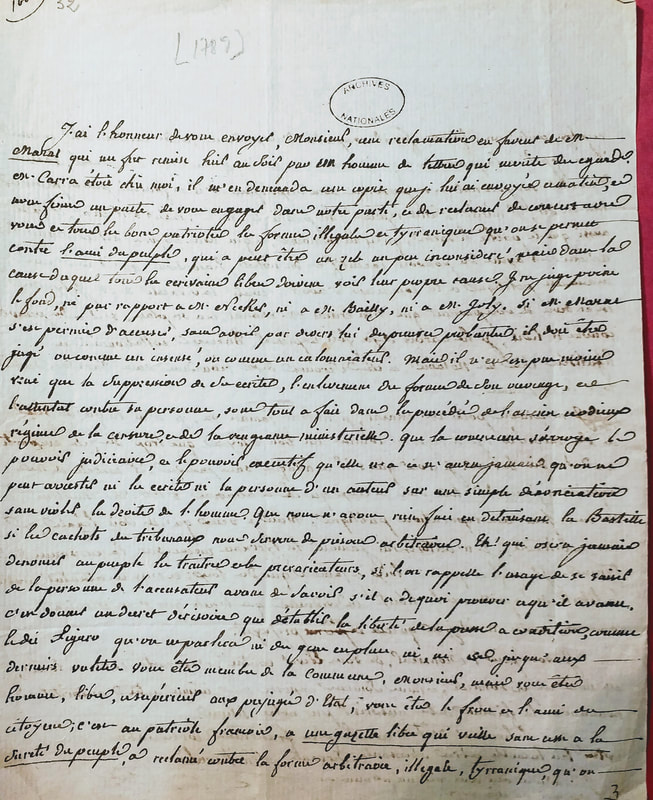

In the Archives Nationales, I found a set of letters from Louise Keralio to Jacques Pierre Brissot. The letters are kept in a folded paper, which notes that one of the letters is about Marat. The letter in question is undated, but from the reference to Marat’s denunciation of Necker means that the letter must be have been written towards the end of October 1789. Here is a – translated – extract: It is my honour to send you, Monsieur, a claim on behalf of M. Marat which was handed me yesterday evening by a man of letter who deserve our consideration. M. Carra was at my home, and asked me for a copy that I sent him this morning, and we made a pact to win us over to our side and to [?] with you and all good patriots against the illegal and tyrannical acts that have been allowed against the ‘Ami du Peuple’ whose zeal is perhaps a little inconsiderate, but for in cause all free writers should recognize their own. I do not judge of the content with respect to M.Necker, M.Bailly or M. Joly. If M.Marat allowed himself to make accusations without probable proofs, he must be judged either as a madman or a slanderer. It is nonetheless the case that to suppress his writings, and to attack his person belond entirely to the ancient and odious regime of censorship and ministerial revenge. […] One cannot put a stop to the writings or the person of an author on a simple denunciation without violating the rights of man. We have done nothing by destroying the Bastille if the tribunal’s lock-ups serve as arbitrary prisons. Louise Keralio was then already a friend and correspondent of Brissot – they had advertised each other’s journals, and praised each other’s work and ideas. Keralio had not, however, met Marat, and had only read a few articles by him. She supposes that Marat is a good citizen whose zeal has carried him beyond acceptable limits. But what she cares about is that the French Press should be treated legally, and not tyrannically. She cites Beaumarchais’ Figaro, jesting that the press should be free, provided it does not mention important people, religion, or anything contentious. She begs Brissot to use his influence to interfere on behalf of Marat, l’Ami du Peuple, and make sure that he is asked to present his proofs so that if he has them, it is known that he did not slander Necker, Bailly and Joly, and that if he doesn’t, the reputation of these three will be cleared in the eyes of all.

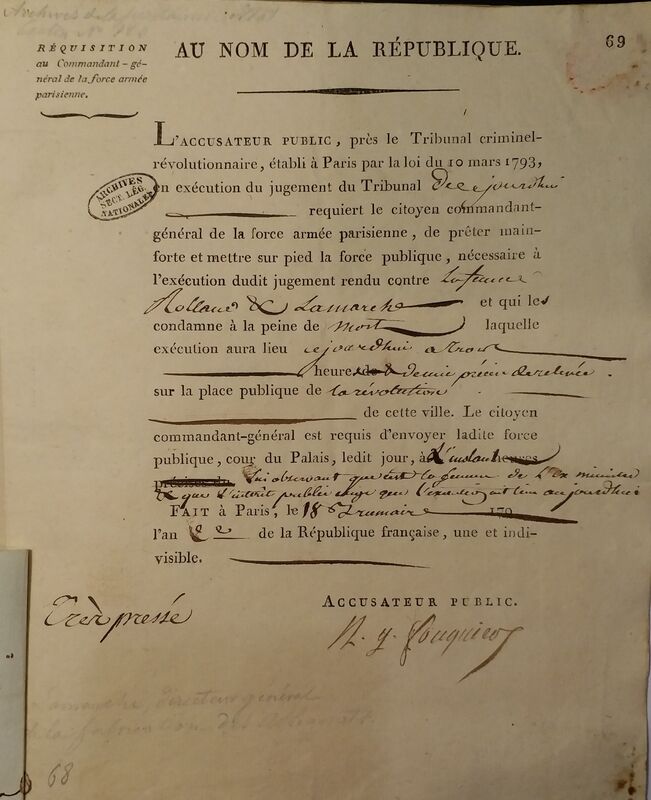

Marat quickly came to be regarded as a threat by the Girondins – especially after he voiced his opinion that the best way to safeguard the revolution would have been to cut off six hundred heads. He went into exile, came back, was tried, imprisoned for a month, and acquitted before he became one of the leaders of the Terror. In September 1792, he tried to have Brissot arrested. One wonders if Brissot looked back then, on Louise Keralio’s petition three years earlier, that he should stand up for Marat… Marat was murdered in July 1793, by Charlotte Corday, who’d decided that by killing Marat she could put a stop to the Terror and protect the republic. Beginning in the summer 1793, Antoine Quentin Fouquier-Tinville, public prosecutor of the Revolutionary Tribunal, signed hundreds of death decrees. Prisoners of the Republic were moved from their prison to the Conciergerie a few days before their trial, and they were tried in the Palais de Justice next door. When found guilty, they were generally executed within one or two days of the judgment. One decree stands out as having happened even faster: that of Manon Roland (whose name is misspelt in the document ordering her death). Manon was killed on the very same day she was condemned. The document above, a printed form filled in with the relevant details, asks the commendant-general of the Paris armed forces to organize the execution of the 'widow Rolland' - and her unfortunate companion, Lamarche, Armed soldiers were to pick up the condemned from the 'Palace court' outside the Conciegerie, and escort them to the Place de la Revolution, where they would be executed at 3:30pm exactly. The armed men were to be dispatched 'immediately'. To this Fouquier-Tinville adds the following by way of explanation: Bear in mind that this is the wife of the ex-minister and that for the sake of the public interest it is imperative that she should be executed today. Given that no-one expected Manon to act in any way dangerously, we must suppose that what Fouquier-Tinville feared was that public sentiment would act against him if it became known that Manon Roland was condemned to die.

Just in case the commandant-general didn't get the message, Fouquier Tinville adds in the bottom left of the page 'very urgent''. Pierre-Jean-George Cabanis, Sophie de Grouchy's long time friend, the C*** of her Letters on Sympathy, and husband of her sister Charlotte, and Claude Fauriel, Sophie's lover from 1801 till her death in 1824, developed a close friendship from the time Fauriel became part of their circle in 1801 till Cabanis died in 1808.

Cabanis's text on Stoicism and Physiology, The Letter on First Causeswas written to and for Claude Fauriel. Fauriel intended to write a book about Stoic philosophy (the manuscript was lost before he could finish it). The few personal letters from Cabanis to Fauriel that survive give this sense of a nineteenth century ‘bromance’, with Cabanis writing excitedly to Fauriel that Sophie’s father has reserved the room next to his own for his upcoming visit, and signing off his letters with tender embraces and assurances of ever lasting love. In one of his letters, he enquires after Fauriel’s project of a Greek History, and promises him the notes made by Garat on a similar topic. Garat was either Sophie's ex, Mailla Garat, or his older brother: in neither case, does it seem like it was an entirely appropriate person to turn to! His friendship with Cabanis still resonated in Fauriel's life long after both Cabanis and Sophie's deaths. Cabanis’s widow, who was also Sophie’s sister, Charlotte, in her correspondence with Fauriel refers to a person they both loved and lost, for whom they felt ‘a huge, and unshakeable tenderness, which must be very deep and sweet until your last day’. She meant her husband, not her sister.And when she claims his time and affection, it is as the ‘companion of the man you loved so’, and not as the sister of his life partner.

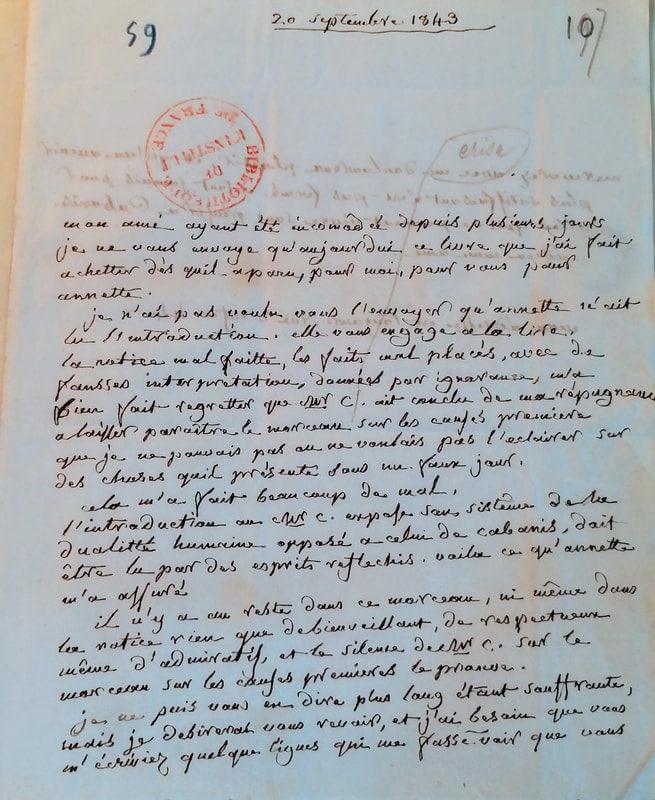

The posthumous publication of the Letter on First Causes, which happened towards the end of Charlotte Cabanis’s life, was a cause for much concern for both Fauriel and Charlotte. Charlotte had allowed the Letterto be published, but she had had no control over the process, and only read the introduction once it was in print. She found it full of mistakes and bad interpretations, and reflected that the author of the introduction was more interested in promoting his own dualism than making Cabanis’s view clear. The last few letters exchanged between Fauriel and Charlotte Cabanis concern the publication of a bibliographical notice on Cabanis, a project that Daunou had offered to take on before he died. There is much discussion as to whom might be a good person to edit Cabanis’ s paper, and once the choice is made, about how much control his widow might be able to exercise over the process. At no point during the correspondence is Sophie mentioned, even though she died 14 years after Cabanis, and had thus been part of Fauriel’s life much longer. The biographical notice, based on a text drafted by Cabanis himself, was written by Peisse, and published alongside an edition of the Rapports du Physique et du Moral and the Lettre sur les Causes Premieres by Destutt de Tracy in 1844. That same year, perhaps even before the book was out, Claude Fauriel and Charlotte Cabanis died, both in their seventies. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed