|

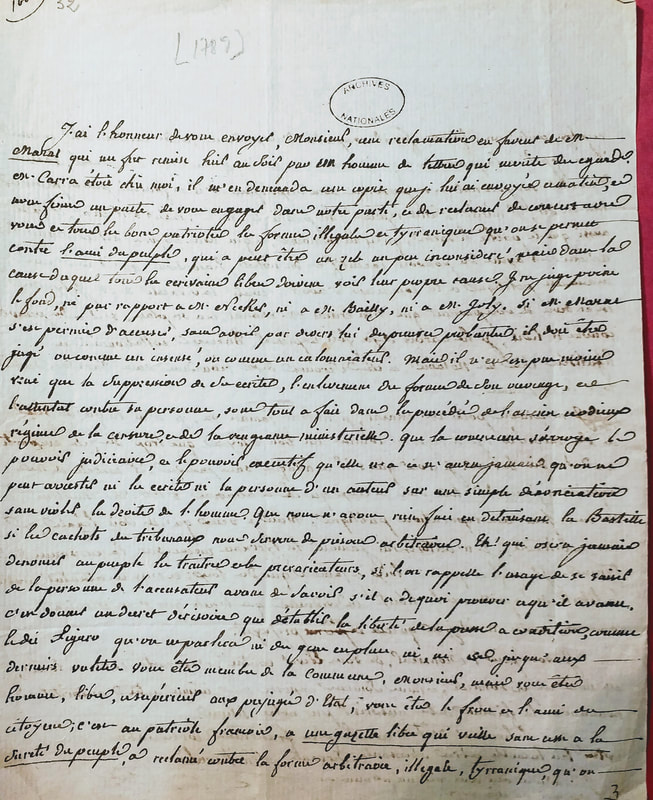

In the Archives Nationales, I found a set of letters from Louise Keralio to Jacques Pierre Brissot. The letters are kept in a folded paper, which notes that one of the letters is about Marat. The letter in question is undated, but from the reference to Marat’s denunciation of Necker means that the letter must be have been written towards the end of October 1789. Here is a – translated – extract: It is my honour to send you, Monsieur, a claim on behalf of M. Marat which was handed me yesterday evening by a man of letter who deserve our consideration. M. Carra was at my home, and asked me for a copy that I sent him this morning, and we made a pact to win us over to our side and to [?] with you and all good patriots against the illegal and tyrannical acts that have been allowed against the ‘Ami du Peuple’ whose zeal is perhaps a little inconsiderate, but for in cause all free writers should recognize their own. I do not judge of the content with respect to M.Necker, M.Bailly or M. Joly. If M.Marat allowed himself to make accusations without probable proofs, he must be judged either as a madman or a slanderer. It is nonetheless the case that to suppress his writings, and to attack his person belond entirely to the ancient and odious regime of censorship and ministerial revenge. […] One cannot put a stop to the writings or the person of an author on a simple denunciation without violating the rights of man. We have done nothing by destroying the Bastille if the tribunal’s lock-ups serve as arbitrary prisons. Louise Keralio was then already a friend and correspondent of Brissot – they had advertised each other’s journals, and praised each other’s work and ideas. Keralio had not, however, met Marat, and had only read a few articles by him. She supposes that Marat is a good citizen whose zeal has carried him beyond acceptable limits. But what she cares about is that the French Press should be treated legally, and not tyrannically. She cites Beaumarchais’ Figaro, jesting that the press should be free, provided it does not mention important people, religion, or anything contentious. She begs Brissot to use his influence to interfere on behalf of Marat, l’Ami du Peuple, and make sure that he is asked to present his proofs so that if he has them, it is known that he did not slander Necker, Bailly and Joly, and that if he doesn’t, the reputation of these three will be cleared in the eyes of all.

Marat quickly came to be regarded as a threat by the Girondins – especially after he voiced his opinion that the best way to safeguard the revolution would have been to cut off six hundred heads. He went into exile, came back, was tried, imprisoned for a month, and acquitted before he became one of the leaders of the Terror. In September 1792, he tried to have Brissot arrested. One wonders if Brissot looked back then, on Louise Keralio’s petition three years earlier, that he should stand up for Marat… Marat was murdered in July 1793, by Charlotte Corday, who’d decided that by killing Marat she could put a stop to the Terror and protect the republic.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed