|

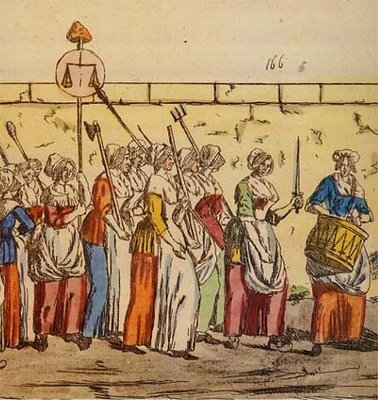

In 1788, when he first presented his ‘What is the third estate’, the Abbé Sieyès declared that : “inequalities of sex, size, age, colour, etc. do not in any way denature civic equality” (Sieyes, Political Writings, 155). These, he said, like inequality of property, are incidental differences and cannot affect civic rights. But Sieyès, it turns out, was not so committed to equality, however, that he wanted to extend rights active citizenship to women. In his Préliminaire de la Constitution, written on 22 July 1789, he writes: All of a country’s inhabitants must enjoy the rights of passive citizenship: all have the right to the protection of their person, their property, their freedom, etc. But not all have the right to take an active part in the formation of public powers, all are not active citizens. Women, at least in the current state of things, children, foreigners, those that contribute nothing to supporting the public establishment must not actively influence the republic. Women did not remain silent. Then journal editor, Louise Keralio, responded four weeks later: We don’t understand what [Sieyès] means when he says that not all citizens can take an active part in the formation of the active powers of the government, that women and children have no active influence on the polity. Certainly, women and children are not employed. But is this the only way of actively influencing the polity? The discourses, the sentiments, the principles engraved on the souls of children from their earliest youth, which it is women’s lot to take care of, the influence which they transmit, in society, among their servants, their retainers, are these indifferent to the fatherland?... Oh! At such a time, let us avoid reducing anyone, no matter who they are, to a humiliating uselessness. Keralio is clearly angered by Sieyès’ formulation: in what sense are women not active, she asks? What is there of passivity in the work they conduct from the home, nurturing republican values and giving birth to new citizens? Like Manon Roland, she was a reader of Rousseau, and was convinced that there was a place for women in Republic that was central to the flourishing of the nation, even though that place was in the home rather than in the assembly. So she does not disagree with Sieyes that women should stay home, rather than participate in debates taking place in public fora, but she believes that the home is just as important a place for the making and cultivating of the republic than the assembly. Olympe de Gouges’s famous response was printed at the same time as Louis XVI ratified the constitution drafted by Sieyès, in September 1791. Man,” she asks “are you capable of being fair? A woman is asking: at least you will allow her that right. Tell me? What gave you the sovereign right to oppress my sex? Your strength? Your talents? Observe the creator in his wisdom, examine nature in all its grandeur for you seem to wish to get closer to it, and give me, if you dare, a pattern for this tyrannical power. On behalf of women in general, she expresses her outrage that women have been exclude from active participation in the city, with no argument, other than that they belonged to the class of those who ‘contribute nothing to supporting the public establishment’. Women, she knows, contributed both physically – by fetching the royal family from Versailles – intellectually – by debating new ideas in circles and political societies, publishing pamphlets proposing reforms (such as her proposal for a voluntary tax) – and materially – by giving money and jewels to relieve poverty and help pay off the national debt. Unlike Louise Keralio, she does not even feel that she needs to appeal to women’s contribution to the republic quamothers. Yet, she does not hesitate to remind the public that women are also mothers: Mothers, daughters, sisters, representatives of the Nation, all demand to be constituted into a national assembly. Given that ignorance, disregard or the disdain of the rights of woman are the only causes of public misfortune and the corruption of governments [they] have decided to make known in a solemn declaration the natural, inalienable and sacred rights of woman; this declaration, constantly in the thoughts of all members of society, will ceaselessly remind them of their rights and responsibilities, allowing the political acts of women, and those of men, to be compared in all respects to the aims of political institutions, which will become increasingly respected, so that the demands of female citizens, henceforth based on simple and incontestable principles, will always seek to maintain the constitution, good morals and the happiness of all.

0 Comments

On 26 July 1789, Manon Roland wrote the following to her friend Louis-Augustin Bosc d'Antic: No, you are not free; no one is yet. The public trust has been betrayed. Letters are intercepted. You complain of my silence and yet I write with every post. It is true that I no longer offer up news of our personal affairs : but who is the traitor, nowadays, who has any other than those of the nation? It is true that I have written you more vigorously than you've acted. But if you are not careful, you will have done nothing but raise your shields. [...] Bosc d'Antic was a thirty year old botanist, who had just founded the first French Linnean society. But as a close friend of the Rolands, he was also a republican, and keen for France to change. In 1791, he became Secretary of the Jacobin's club. It is not clear what role he played before then. Manon Roland mentions 'his districts' - the old parishes, which under the Commune became 'Sections' - which leads one to suppose that he had been elected at the Assembly of June 89, sworn to give France a Constitution. His name does not feature, however, among the 300 Parisian members. Certainly, however, he and Roland's two other correspondents at the time, Lanthenas and Brissot, were active and influential. And they listened to her, asking for her advice and opinion on what to do. Brissot even published some of her letters in his new paper, Le Patriote Francois.

Clearly Manon was worried that the Revolution would peter out, because her friends did not act firmly enough. She was only just recovering from a life threatening illness, and still nursing her husband, so could not come to Paris herself to see to it that things were done properly. * The 'illustrious heads' she says must be tried are the king's brother and the king's wife, who were then believed guilty of a failed coup d'Etat. ** Decius, is Decimus Brutus, not the Emperor Decius. *** "You are f..." is in French "Vous etes f...". She no doubt wrote, or intended it to be read 'foutus', which means exactly what my translation suggests. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed