|

The following is translated from the description of an exhibition of Korean artist Nam June Paik (1932-2006) at the Grand Palais in Paris, in June-July 2018. "Olympe de Gouges (1989) – writer, feminist pioneer and anti-slavery activist, executed in 1793 – is a robot made out of twelve CTR colour televisions inserted in a frame made out of twelve wooden ancient tvs. The work itself is on laser VD. On the sides are painted chinese characters meaning “French woman, Truth, Goodness, Beauty, Liberty, Passion” refering to the wording of the commission to the artist by the City of Paris for the celebrations of the bicentenial of the French Revolution in 1789."

0 Comments

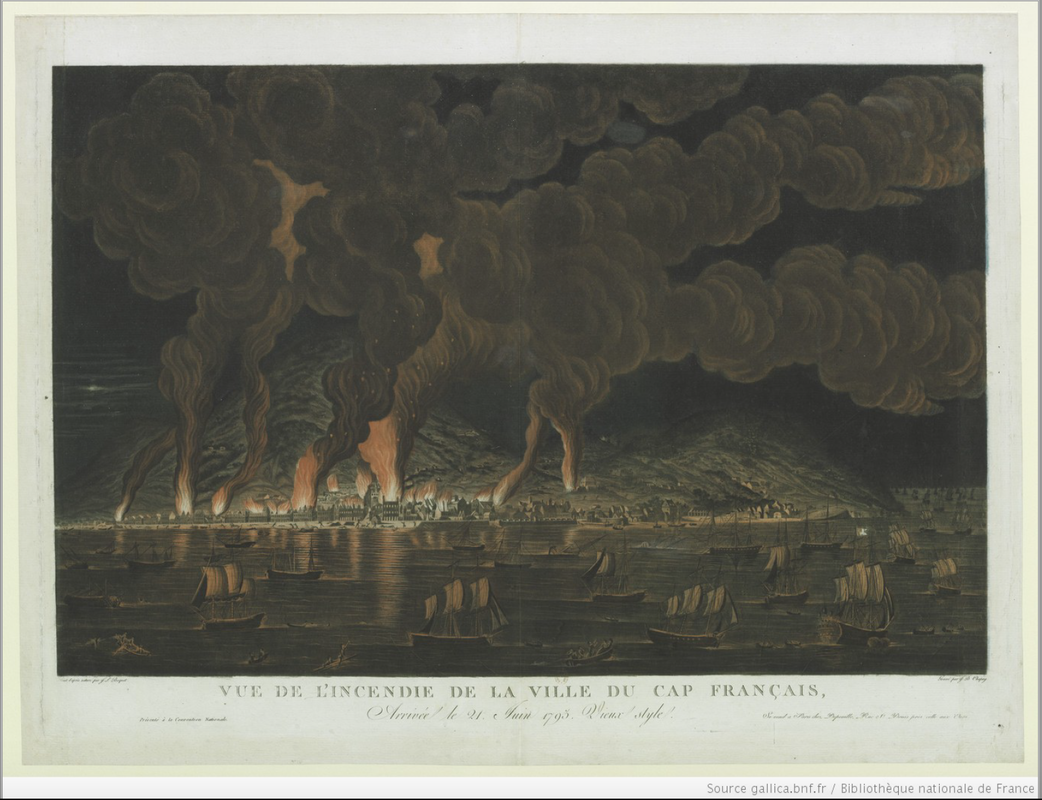

In August 1791, the slaves of Saint-Domingue revolted. They were joined by free people of colour, and together they set plantations on fire. The whites fought back and the violence escalated on both sides.

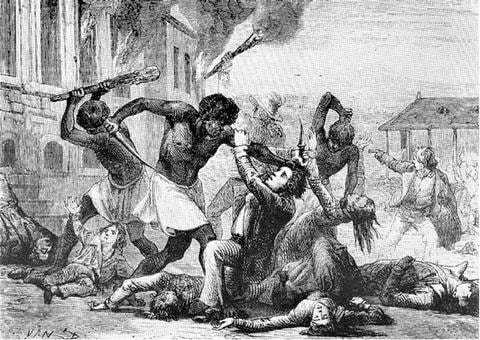

Either because she was actually blamed, or because she felt she would be blamed, or again because she thought that her work was relevant to what was happening and needed to be defended, Gouges brought out a new edition of her play, Zamore and Mirza in March 1792. In the preface of that edition Gouges attempted to defend her work against its detractors: she repeated what she had said in her open letter in 1790, that did not incite revolt, and that her motives were philanthropic and had justice on their side. She acknowledges that she prophesized the revolution, but claims that it was ‘an invisible hand’ that started it, and that she herself is blameless. But rather than spending time defending herself, or even reminding the colonists that ‘she told them so’ and that they are responsible for what happened to them to a large extent – she thinks they have suffered enough – Gouges decided to lecture those she had previously defended: the slaves and free men of colour. Her admonition is in two parts. First, she blames the Haitian revolutionaries outright for their ‘ferocity’ and ‘cruelty’ telling them that by their actions they demonstrate that they belong in chains, that they are more brute than human. She acknowledges that her evidence is hearsay – she has read reports from white men of crimes committed by black men. Yet, perhaps because she has witnessed similar crimes being committed in Paris, she is inclined to believe these reports. One cannot help sensing that Gouges had placed great trust in these people she had not met, that she had seen in them something close to her own ideal of human nature – unsophisticated nature of the sort she felt was most suited to happiness. Even now she claims that slaves and people of colour live ‘closer to nature’ than their tyrants, the white colons, do. This makes little sense even if she is only addressing slaves. What does she mean by living closer to nature? It cannot be to live as nature intended, as they are slaves and she does not believe slavery is natural. Is it simply wearing fewer layers of protective clothing and spending more time outside in the heat? If so, how can she regard this as a good thing? The climate of Haiti was ill-suited for field work, and the black slaves suffered from it as much a white workers would have, the only difference being that they had no choice but to work until they dropped. Her claim is even more puzzling in the case of free people of colour, whom Gouges addresses in that same sentence, and who lived lives very much like those of the white colonists. They owned property, or worked in the city, and had their own slaves. They received the same education as their white peers did, and some, who had been sent to France to learn, were indeed better educated (which created some resentment amongst the poorer white colonists). Her close acquaintance, Joseph Boulogne, Chevalier de Saint-George, was an aristocrat, a colonel in the army, and an influential musician whose name was put forward for the direction of the Paris Opera. Saint-George was probably living as far from nature as it was possible to do in the late 18thcentury! In the colonies themselves, many free men and women of colour were better off than the whites. Their ancestors had inherited lands at a time when it was plentiful, and the family wealth had had time to grow, so that they were better off than newly arrived white families – which created a certain amount of resentment. The colonies were also full of white paupers, the ‘pacotilleurs’ who made a living selling poor quality merchandise. These were the real lower class of the free Haitian society. So it is a mystery what Gouges is trying to say when she claims that those people lived ‘closer to nature’ than their tyrants. In the second part of her admonition Gouges asks that the slaves, instead of revolting, should wait for the ‘wise laws’ to see to it that they receive just treatment. And the free men of colour, she says, should count their blessings. The French Nation has given them more freedom than they ever had, she says. And both slaves and free men of colour are better off, she says, in the colonies than they were in their own countries, where their own parents sold them into slavery, where human beings are being hunted like animals, and in some cases eaten too. There is something very strange with hindsight, in Olympe’s atttitude to the revolutionary Haitians. She seems very willing to take seriously the reports of those she still calls the ‘Odious colonists’, and shows no effort to find out how much truth there is in them. The very idea, it seems, that her beloved victims have turned violent against their tyrants shocks her. Yet, even Zamore et Mirzashows a hero who murdered his master, and who is at the end of the play, pardoned. In 1792, upon hearing reports of plantations being set on fire by rebelling slaves in Saint Domingue, and white colonists being tortured and murdered, Olympe decided to reprint her abolitionist play, Zamore and Mirza, with a new preface justifying what she still saw as a philanthropic work. But she was clearly rattled by the violence she heard of. Yet the reports were one-sided: the white colonists wrote home asking for help, slaves and free men of colour were busy acting and planning their revolution. But there were some reports of mindless violence on the part of white colonists too, and those had started before the revolution. One such act was the mobbing and murder of a respected and well loved seventy year old mulatto plantation owner, Guillaume Labadie, whose home in Aquin was invaded under false pretenses – rumours that he was holding a meeting of men of colour – by twenty five white men who shot him and tied him to the tail of a horse, dragging the wounded man around town until he was dead. An account of this was published by Julien Raymond, in a letter to Brissot, at the end of his book on colonial prejudices. It is possible that Gouges would have heard of it. But one report from those who are habitually abused does not have the same effect as panicked letters coming in from the colonies by those who thought themselves safe. Pictures of plantations in flames were published, and no doubt the events themselves were exaggerated – for after all, who would check? Travel to Haiti was difficult and took enough time that by the time someone from France would get there the dead would have been long buried. Gouges’ reaction was twofold. First, she decided to admonish the slaves and men of colour she had previously defended, telling them that they were worse than their tyrants, and the if no man was born to live in chains, they showed them to be necessary.

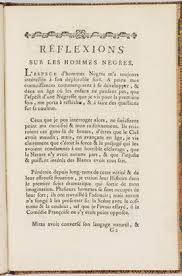

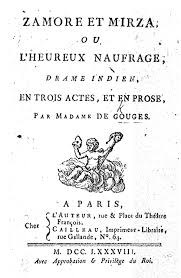

Secondly, she decides that no good can come from trying to apply philosophical ideas to the real world. Writings such as her own Le Bonheur Primitif, Rousseau’s On Social Contract, and unnamed but ‘august’ writings by Brissot, she says, although they are admirable, can never be truly useful as the establishment of new doctrines will always cause more evil along the way than good. “It is easy even for the most ignorant man to start a revolution with a few exercise books.” Revolutionary France has drawn plenty evil from Rousseau’s writings, defacing them by turning them into calls for violence. What chance, she asks would Brissot’s and her own writings on slavery stand in such a climate? One is led to ask why it was so easy for Gouges to turn her back on those she had previously defended - if indeed that is what she was doing. But more on this later. In 1783 Olympe wrote her first play, Zamore et Mirza, ou l’heureux naufrage, and submitted to the Comédie Française. The actors liked it and accepted it. Unfortunately, her later dispute with Beaumarchais over Le Marriage Innatendu de Chérubin, meant that the Comédie just sat on her play and refused to put it on. The contract she had signed with them meant that it could not be played elsewhere in Paris. So Olympe took the play elsewhere, with her own theatrical troup, which included her son, and performed it in private theatres and in the provinces. In 1786, she had the play printed for the fist time. Two years later, she printed it again, with a postface, her “Réflections sur les hommes nègres” in which she explained what the philosophy behind the play was. Why are black people treated like animals, she asked? [I] clearly observed that it was force and prejudice that had condemned them to this horrible slavery, that Nature had no part in it and that the unjust and powerful interest of the Whites was responsible for it all. In 1788, Olympe was already sensing a change for the better in politics, and felt it her duties to show the world that if they wanted to redress injustice, slavery was the place to start: When will work be undertaken to change it, or at least to temper it? I know nothing of Governments' Politics, but they are fair, and never has Natural Law been more in evidence. They cast a benevolent eye on all the worst abuses. Man everywhere is equal. As she pointed out in January 1790, in an open letter to an (anonymous) American colonist attacking her play, at the time she wrote Zamore and Mirza, there was no organised French abolitionist movement. The Societé des Amis des Noirs did not yet exist. She ponders in that letter, whether it was her play that caused Brissot and the others to create that society, or whether it was just a happy coincidence: I can therefore assure you, Sir, that the Friends of the Blacks did not exist when I conceived of this subject, and you should rather suppose that it is perhaps because of my drama that this society was formed, or that I had the happy honour of coincidence with it. In fact, Brissot did take note of the play, and in the winter 1789, he made use of his growing influence to persuade the actors of the Comédie Française, finally to put it on. Unfortunately, the actors bore a grudge, so they arranged for the play to be put on on the last day of the year, after which Parisians would be returning to their family homes to celebrate the New Year. The contract required that a play make a certain amount of money in the first three days if it was to stay on the program. The first night was a success – but a political rather than an artistic one. People came to support it and to protest against it, and they were so loud about it, that few could hear the actors. Fortunately the text was in print, and reviewers at the time noted that they’d had to refer to the printed version to know how the play ended. Those who protested against the play most vociferously were the colonists, who had strong financial interest in the laws regarding slavery staying as they were. One such colonist wrote to Gouges, imputing that she was but the tool of Brissot’s society, and that her play was a call for the slaves of America to revolt. Gouges responded in an open letter, (1790) arguing, as we saw, that it was she, not Brissot, who’d first given voice to the abolitionist in France, and that her play did not incite revolution, but that it enjoined the French people and the colonists to see that all men were equal and abolish slavery, and the slaves to trust in the new laws and wait for a better future. Two years later, these accusations came back when the slaves and the free people of colour of Saint-Domingue revolted. In 1788, despairing that her play on slavery, Zamore and Mirza, would never be produced – the ComédieFrançaise had taken it on two years previously, but were holding it hostage for obscure reasons – Olympe decided to publish it on her own account. The title page announces that the book was printed in Paris, and that it may be bought at the author’s own house, rue du ThéâtreFrançais. At the end of the book, she added a short (7 pages) essay, entitled: “Réflexions sur les hommes negres.” In this piece she gives an account of how she first became interested in the fate of slaves in the colonies, and what she sees as a fundamental flaw in pro-slavery arguments : namely, there are no natural differences between human beings based on their skin colour. Here are extracts from her argument: “As soon as I began to acquire some knowledge, and at an age where children do not yet think, the first sight of a negro woman led me to reflect, and to ask questions about colour. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed