|

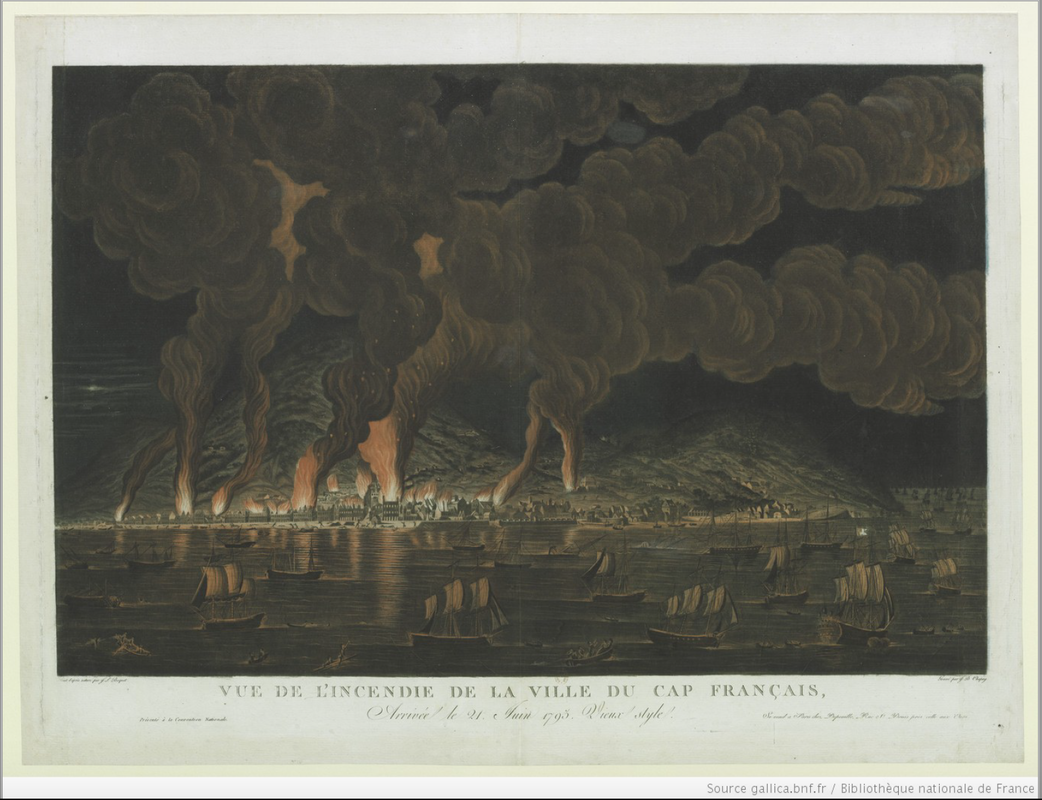

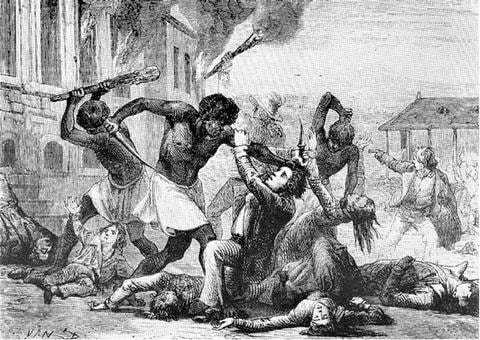

In 1792, upon hearing reports of plantations being set on fire by rebelling slaves in Saint Domingue, and white colonists being tortured and murdered, Olympe decided to reprint her abolitionist play, Zamore and Mirza, with a new preface justifying what she still saw as a philanthropic work. But she was clearly rattled by the violence she heard of. Yet the reports were one-sided: the white colonists wrote home asking for help, slaves and free men of colour were busy acting and planning their revolution. But there were some reports of mindless violence on the part of white colonists too, and those had started before the revolution. One such act was the mobbing and murder of a respected and well loved seventy year old mulatto plantation owner, Guillaume Labadie, whose home in Aquin was invaded under false pretenses – rumours that he was holding a meeting of men of colour – by twenty five white men who shot him and tied him to the tail of a horse, dragging the wounded man around town until he was dead. An account of this was published by Julien Raymond, in a letter to Brissot, at the end of his book on colonial prejudices. It is possible that Gouges would have heard of it. But one report from those who are habitually abused does not have the same effect as panicked letters coming in from the colonies by those who thought themselves safe. Pictures of plantations in flames were published, and no doubt the events themselves were exaggerated – for after all, who would check? Travel to Haiti was difficult and took enough time that by the time someone from France would get there the dead would have been long buried. Gouges’ reaction was twofold. First, she decided to admonish the slaves and men of colour she had previously defended, telling them that they were worse than their tyrants, and the if no man was born to live in chains, they showed them to be necessary.

Secondly, she decides that no good can come from trying to apply philosophical ideas to the real world. Writings such as her own Le Bonheur Primitif, Rousseau’s On Social Contract, and unnamed but ‘august’ writings by Brissot, she says, although they are admirable, can never be truly useful as the establishment of new doctrines will always cause more evil along the way than good. “It is easy even for the most ignorant man to start a revolution with a few exercise books.” Revolutionary France has drawn plenty evil from Rousseau’s writings, defacing them by turning them into calls for violence. What chance, she asks would Brissot’s and her own writings on slavery stand in such a climate? One is led to ask why it was so easy for Gouges to turn her back on those she had previously defended - if indeed that is what she was doing. But more on this later.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed