|

Around the time that the guillotine was first tried, Sophie de Grouchy was finishing a draft of her Letters on Sympathy. The letters are a both a commentary and a response to Adam Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments in which the Scottish philosopher argued that morality arises out of our reactive attitudes and the sympathythat human beings naturally feel for each other. For Grouchy sympathy develops from the first relationship an infant experiences, that is from the proximity with another living body, and the dependence it develops with it. Because sympathy is developed through contact with others, it is natural that the Letters discuss crowd psychology: Amongst the effects of sympathy, we can count the power that a large crowd has to affect our emotions [...]. Here are, I believe, a few causes of these phenomena. First, the very presence of a crowd acts on us through the impressions created by faces, discourses, or the memory of deeds. The attention of the crowd commands ours, and its eagerness, forewarning our sensibility of the emotions it is about to experience, sets them in motion. This passage is reminiscent of the Roman Stoic philosopher Seneca’s Letter to Lucilius, in which he describes the powerful – and worrying – effect that crowds can have on the wisest, calmest of individuals. He writes how, on occasions when the emperor forced him to attend gladiator shows, his blood was raised and he too wanted to shout that one should die and another live. To consort with the crowd is harmful; there is no person who does not make some vice attractive to us, or stamp it upon us, or taint us unconsciously therewith. Certainly, the greater the mob with which we mingle, the greater the danger. Grouchy tried to pinpoint the cause of this response. It is the overwhelming presence of living bodies, all in one place, all speaking, moving, twitching in their own way, but at the same time all focusing their attention on the same point, which both confuses us and takes over our own sense of direction: we too want to look where they look, and we too are getting excited with the anticipation of what will happen there. The description of the effect of crowds in the Letterson Sympathyalso touches on the paradox of tragedy – why do we enjoy tragedy so, if we find other’s pain distasteful? The question is as old as Aristotle, who saw in tragedy a way to educate one’s emotion, to learn to understand and manage them. This is also where Grouchy is going here: In any case, we know that the spectacle of physical suffering is a real tragedy for the masses, a tragedy they seek only through a dumb curiosity, but whose sight sometimes arouses the kind of sympathy which can become a passion to contend with (Letter 4). No doubt Grouchy also has the spectacle of the public execution in mind here. When she first drafted the letters, executions were most commonly hangings, and they were always public, in France as elsewhere. People came to watch, and bought snacks and souvenirs, as they would at the theatre. And as we know, a year after writing this, she mingled with the crowds going to the guillotine, in order to visit her husband in hiding.

0 Comments

In 1798, Sophie de Grouchy published her Letters on Sympathy. We know that she already had a draft in 1791, which she'd sent to her friend Dumont for feedback that never came. We know that the Letters were complete in 1794, and that they had a title, as Condorcet refers his daughter to them in his Testament. So why were they only published in 98? We don't know as she did not leave an account. But it's likely the answer lies either in need, opportunity or both. After the Terror, Sophie needed money, and she decided to translate Smith's Theory of Moral Sentiment. Smith was very popular, and existing translations of this text were not particularly good, so there was a clear gap in the market. This also gave her the opportunity to publish her own short text. Her Letters were after all a critique and commentary of Smith. So she appended them to the translation. Although the Letters are in fact a more like a treatise than a record of correspondence (there is in fact only one letter writer involved), each chapter is set out as a letter to someone addressed as C***, announcing the topic of discussion, linking it to the previous one, and at the end, drawing out the conclusions to be taken forward to the next chapter. C*** is also an excuse for considering objections to Grouchy's arguments, with many paragraphs starting with formulas such as "No doubt you will tell me, my Dear C***". So C*** is very much a philosophical interlocutor, the Platonic touchstone to Sophie's Socrates. So who is C***? The obvious assumption is that it is Sophie's husband, Condorcet. But there are reasons why this is probably not true. First, her husband was dead by the time the Letters were prepared for publication. Secondly, if Sophie was to record a fake dialogue with a real person then she would probably have picked someone she actually corresponded with - in 1791, when the letter were written, Sophie and her husband were not apart long enough to correspond. But there were at least two more Cs in Sophie's life, to whom she was very close, with whom she did correspond and who were still alive when the Letters were published. They were her sister Charlotte, and Condorcet's close friend, Pierre George Cabanis. Of the two, C*** cannot be Charlotte, as 'My Dear C***' in French is 'Mon Cher C***' which is masculin. So Cabanis is more likely. Cabanis, as it happens, did correspond with Sophie on topics very close to her Letters, on Physiology, a materialist science aiming to understand human beings through their bodily organs. In 1802, Cabanis published his Rapports du Physique et du Moral de l'Homme, in which he explores the relations between bodies and morality, discussing for instance, the influence of weather and digestion on mood and decision making. Prior to publishing this, he corresponded with Sophie, and had long discussions with her on the subject.

Physiology is also central to the Letters on Sympathy, as Sophy argues that our moral feelings are born out of the physiological response that ties a newborn to the person that nurses her and holds her. Cabanis and Charlotte de Grouchy became lovers during the Revolution, and in 1796, they were married. Some readers like to see a love story behind every text (in particular, texts written by women!) but in this case, we must suppose that C*** was very much an intellectual interest (and a close family friend) but not a love interest. Cabanis was by profession a doctor in medicine but did not practice. Some say that was because of his own poor health. Some say that he was in fact a spy, not a doctor. He is also reputed to have given Condorcet a dose of poison to hide in a ring. And this poison, in some accounts of Condorcet's death, is what he took to kill himself when he was captured in March 1794. In the spring 1792, Sophie de Grouchy, Marquise de Condorcet wrote to her friend Etienne Dumont, speech writer for Mirabeau, and translator for Jeremy Bentham, sending him some of her manuscripts for feedback. "Here are the inchoate manuscripts I mentioned to M.Dumont, or rather the indecipherable sketches. I have lost the eighth letter on sympathy. As to the other mess, it contains as yet only a few weak traces of a development of character and passions, and that is not yet strengthened by any of the circumstances that make a novel interesting. One of the main causes of my laziness when it comes to working on it is 1) difficulty in obtaining good advice (will some arrive from overseas!) 2) the fear of not having the means of executing the ideas which, in other hands could enrich the subject matter, but in mine, will probably make it less. If M.Dumont were to dine here this Tuesday, I would be in a better position to take heed of his advice, but also, they might be more frank if they are in writing. There is no need, I know, to ask him to speak to no-one of that which I send him." Letter to Dumont, spring 1792. Apparently, Dumont did not reply, and either he did not come to dinner, or the conversation did not turn to Sophie's writings.

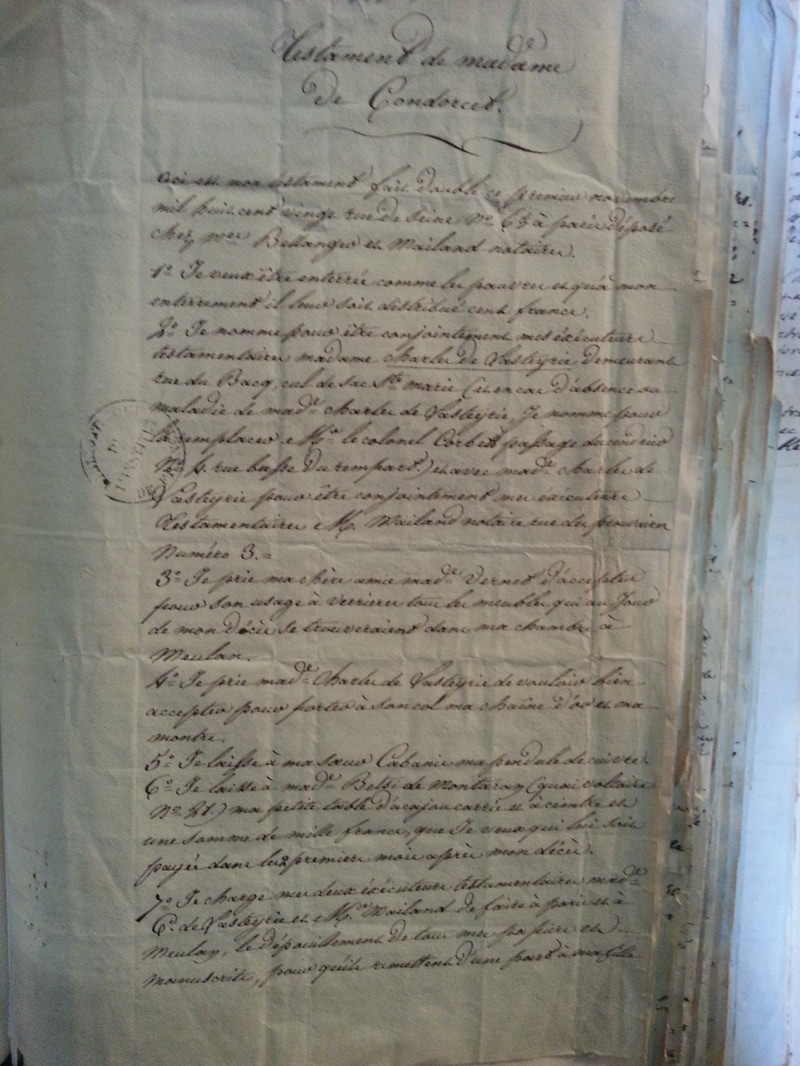

"You are a merciless man for poor authors, especially a for a shameful author like a woman. What would it have cost you to tell me whether what you'd seen from my drafts deserved to be developed? I give you my word you would have had no grief from it." 19 May 1792. Why did Dumont not reply? Perhaps, despite his friendship for Sophie, he was not entirely persuaded that women should waste their time in literary pursuits, or that their contributions would be particularly good. Or perhaps he did not wish to spend his leisure time doing for free what he did for a living! Fortunately, the Letters on Sympathy were already fully drafted, and six years later she published them, together with her translation of Smith's Theory of Moral Sentiments. Unfortunately, we know nothing of the novel. Was she discouraged by Dumont's refusal to talk about it, and did she give in to the laziness she refers to in the first letter? In his testament to his daughter, Condorcet tells us that his wife, Sophie de Grouchy, as well as her Lettres sur la Sympathie, wrote other texts in moral philosophy.

These are apparently lost, along with her manuscript of the Lettres. In the summer 2015 I visited the Bibliotheque de l'Institut in Paris, on the Quai de la Monnaie, where Condorcet and Grouchy used to live, and which houses all the papers related to the Academie Francaise. I was hoping to find some trace of her papers. I found her will, stating that she left her papers to her daughter, Eliza, and her sister, Charlotte Cabanis. Her executor was Madame de Lasteyrie, Lafayette's daughter. Next stop the Cabanis archives? |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed