|

In her Memoirs Manon Roland questions the idea that it is wrong that women should serve as their husband's official secretaries. It is natural that husband and wife should work together she says. It is better for a woman to use her skills and intelligence drafting political pamphlets and letters than intriguing in her salon. Unfortunately, the other Jacobins did think that Roland was intriguing in her salon as well as drafting documents, and that the documents she drafted she did so in secret. Marat called her study a 'boudoir', suggesting that it was the entrance to her private quarters, where she entertained male visitors. The boudoir (a sort of sitting/dressing room, sometimes with a writing desk) was a boundary between the public and the private domain. While a 'salon' was a room used for entertaining visitors, and was as such very public, especially in the home of politically active people, the boudoir was more private and could only receive personal and close friends. But is was not as private as the bedroom, where only family and lovers could be entertained. The Marquis de Sade exploited this ambiguity of the boudoir in one of his books – La Philosophie dans le boudoir (sometimes badly translated as Philosophy in the Bedroom), the boudoir being the place where we can both debate public ideas, and perform private acts.

0 Comments

Israel's Revolutionary Ideas (2014) uses the French Revolution to argue for his greater intellectual agenda which is to show the historical importance of the Enlightenment. Putting the radical ideals of the Enlightenment into practice, he argues, is what the French Revolution was mostly about. Certainly, he is not the only person to think so.

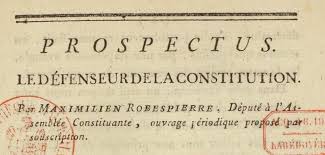

I picked the book hoping to find a narrative that I could use to develop my own understanding of the French Revolution, but also, because I was rather curious as to how he would refer to the women of the French Revolution. His previous books on the Enlightenment have been rather male heavy, with less discussion than one might have hoped, for instance, of Mary Wollstonecraft or Catharine Macaulay. Revolutionary Ideas is no exception: out of 167 names listed as the "Cast of Main Characters", only 8 are women. Some omissions are surprising: Pierre-Francois Robert is listed, but not Louise Keralio-Robert. In the book she is referred to as his collaborator on the Mercure National (p.123). It would be more accurate to say that he had been her collaborator, as it was Louise who started the journal (previously, Le Journal d'Etat et du Citoyen) and she was its editor-in-chief. Robert joined the journal later, and they eventually married. While there are a number of references to both Grouchy and Gouges, they are not particularly enlightening or accurate. Grouchy is referred to as a 'leading exponent of women's rights' but we have no real evidence that she was even interested in women's rights. She did not write about it under her own name – that we know – nor is she reported to have discussed it with anyone. She did, however, contribute in writing and in editing Le Républicain to the leading ideas and arguments of the Revolution. Israel adds her names to various others, including most other women's names (they are rarely mentioned as individuals), also oddly, to Desmoulins's on p.206, and to a list of people who were released from prison after the Terror (she never went!) on p. 582. Olympe de Gouges is referred to as an ex-prostitute ('high class courtisane', p.123), which she certainly was not. She did, as far as we know, have a few lovers over the course of her lifetime, but by that criteria, it's likely that most of the characters listed by Israel were also prostitutes! She also gets the usual treatment of being described as an emotional creature – she is in turns fiery (123), angry (122) and disgusted (400). Gouges is also referred to, several time, as a leading feminist, which she was; but although her other political writings and activities are referred to, it seems that Israel only considers her notable for her feminism, which means that, like Grouchy, the greatest part of her contributions to the ideas that shaped the Revolution are forgotten. Israel is a leading historian of ideas, and Revolutionary Ideas is a very recent book. The fact that it says so little about the women of the French Revolution shows that my project of writing about these women is a much-needed one. In 1792, the conflict between Brissot and Robespierre came to a head, and eventually, a group of people whom we now call the Girondins, left the Jacobin club. Robespierre attacked Brissot in his own journal, Le Defenseur de la Constitution (issue 3, p. 138), and along with Brissot, he criticized his circle of friends, several of whom had been made ministers, arguing that much of their decision-making happened 'behind closed doors' and that they were not, therefore, publically accountable as republican politicians ought to be. Behind closed doors also means inside people's homes. Robespierre was accusing the Girondins of conducting public business outside of the public sphere, and in the private, or domestic one, where women were allowed to talk, and expected to take part in the decision-making. That this was a consideration becomes clear if we read Robespierre's tirade against Jean-Marie Roland. During both of Roland's turns in the ministry, Manon Roland held meetings in their homes. This, for Robespierre, was highly questionable: His house is the rendez-vous of the intriguers who assemble regularly in order to manage the interest of this faction [the Gironde], and the systematic calumnies they direct against the patriots And indeed, later on in the text, as Robespierre unravels what he sees as the extent of Brissot's treachery, he finds that at the end of a 'labyrinth of intrigues', there is a 'female triumvirate' (140). The image of the triumvirate is itself powerful: it refers back to Cesar, Cassius and Pompei taking over the Senate, and eventually destroying the republic. The early days of the Revolution had seen a different triumvirate: Antoine Barnave, Adrien Duport and Alexandre Lameth, constitutional monarchists who eventually left the Jacobins to found their own clubs, the Feuillants. All Jacobins, including the Gironde, had been united in denouncing them. By claiming the existence of a Girondin female triumvirate Robespierre is doing two things. First, he is suggesting that like the Roman and Feuillant triumvirates, this one presents a serious risk to the republic. Secondly, by making it female, he places it 'behind closed doors', in the domestic sphere, and therefore hidden from citizens who might hold it publically accountable.

The identity of Robespierre's female triumvirate is unclear. Marisa Linton, in her excellent book Choosing the Terror, suggests that the three women are Manon Roland, Louise Keralio-Robert and Sophie de Grouchy. Her source is a footnote in a 1939 edition of Le Defenseur de la Constitution by Gustave Laurent. Gita May also names those three women (using the same source) in her 1964 De Jean-Jacques Rousseau a Manon Roland: Essai sur la Sensibilite Pre-romantique et Revolutionaire. But it's very unclear why Laurent gave these three names in the first place. Certainly Manon Roland must be one of the three, as Robespierre mentioned her salon just a few pages earlier. Sophie de Grouchy (Madame Condorcet) also is a likely candidate as Condorcet is very much a target of Robespierre in that article, and because he mentions secret meetings of the Girondin faction with Lafayette, who was a close personal friend of the Condorcets. I'm not clear why Louise Keralio-Robert should be the third woman. She was not a saloniere, but frequented the salon of her neighbours, the Petions, and she was closer to Robespierre than to the Rolands. Other possible candidates for the third member of the Triumvirate would be Germaine de Stael – Brissot did frequent her salon – or Madame Petion. If any one has information about the identity of this third woman, please contact me or leave a comment! While we continue to investigate the lives, deeds and works of the great women of the French Revolution, let's not forget that some of these women were married, and that their husbands sometimes also contributed to the political events of their times. This is not, sadly always the case, and sometimes, what we have are rather petty disputes between men who were not as good at their jobs or deserving of their honour as they might have been!

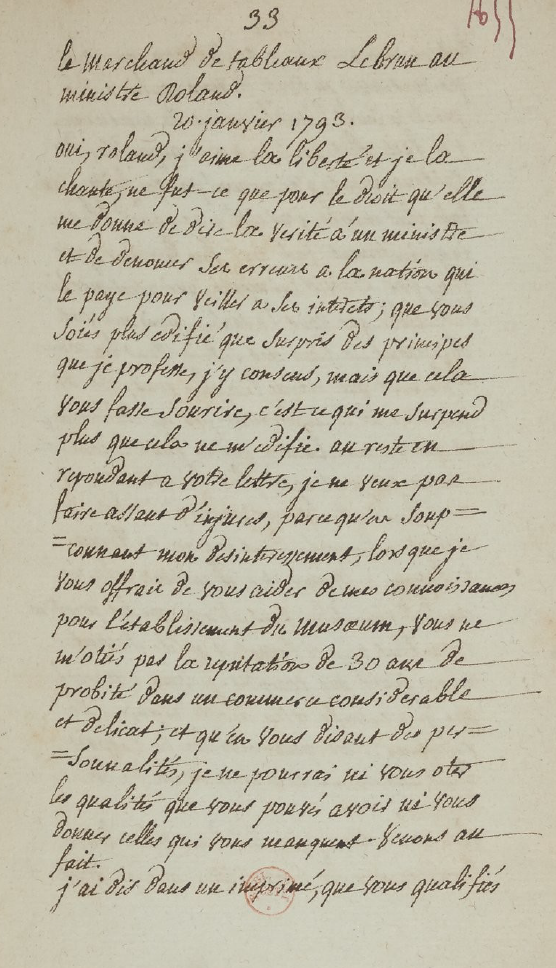

This is partly true of an exchange between Jean-Marie Roland, Manon's husband, and Charles Lebrun, husband to the celebrated painter Elizabeth Vigee-Lebrun. Lebrun was an ambitious art-dealer, supported entirely by his successful wife's earnings and works. However, Vigee Lebrun, who was Marie Antoinette's favorite portraitist, had gone into exile in the early days of the revolution. When she left, she took only 80 louis with her and left most of her fortune with her husband. While abroad she worked and continued to send her some of her substantial earnings to Charles. In order for that money not to be confiscated, Charles asked for a divorce – this was on paper only, and married life resumed as soon as she returned from her 12 year exile. Jean-Marie Roland was minister of the interior – but we know that a lot of his decisions were made by his wife, and that she wrote several influential letters for him. The two husbands came to fight over the question of how to look after the art confiscated from the aristocrats and the clergy. Lebrun thought he should be given the job and paid handsomely to do it. Roland thought this was not a priority. Lebrun published a pamphlet which Roland found insulting and even threatening, and Lebrun responded with an epistolary meltdown, accusing Roland of not being a true republican. I owe the details of this story to Bette W. Oliver's book, Surviving the French Revolution (chapter 4). Here is the first page of Lebrun's letter below, courtesy of Gallica |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed