|

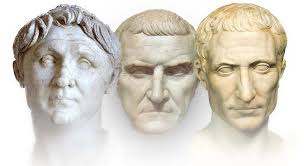

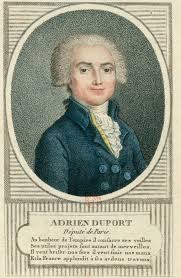

In 1792, the conflict between Brissot and Robespierre came to a head, and eventually, a group of people whom we now call the Girondins, left the Jacobin club. Robespierre attacked Brissot in his own journal, Le Defenseur de la Constitution (issue 3, p. 138), and along with Brissot, he criticized his circle of friends, several of whom had been made ministers, arguing that much of their decision-making happened 'behind closed doors' and that they were not, therefore, publically accountable as republican politicians ought to be. Behind closed doors also means inside people's homes. Robespierre was accusing the Girondins of conducting public business outside of the public sphere, and in the private, or domestic one, where women were allowed to talk, and expected to take part in the decision-making. That this was a consideration becomes clear if we read Robespierre's tirade against Jean-Marie Roland. During both of Roland's turns in the ministry, Manon Roland held meetings in their homes. This, for Robespierre, was highly questionable: His house is the rendez-vous of the intriguers who assemble regularly in order to manage the interest of this faction [the Gironde], and the systematic calumnies they direct against the patriots And indeed, later on in the text, as Robespierre unravels what he sees as the extent of Brissot's treachery, he finds that at the end of a 'labyrinth of intrigues', there is a 'female triumvirate' (140). The image of the triumvirate is itself powerful: it refers back to Cesar, Cassius and Pompei taking over the Senate, and eventually destroying the republic. The early days of the Revolution had seen a different triumvirate: Antoine Barnave, Adrien Duport and Alexandre Lameth, constitutional monarchists who eventually left the Jacobins to found their own clubs, the Feuillants. All Jacobins, including the Gironde, had been united in denouncing them. By claiming the existence of a Girondin female triumvirate Robespierre is doing two things. First, he is suggesting that like the Roman and Feuillant triumvirates, this one presents a serious risk to the republic. Secondly, by making it female, he places it 'behind closed doors', in the domestic sphere, and therefore hidden from citizens who might hold it publically accountable.

The identity of Robespierre's female triumvirate is unclear. Marisa Linton, in her excellent book Choosing the Terror, suggests that the three women are Manon Roland, Louise Keralio-Robert and Sophie de Grouchy. Her source is a footnote in a 1939 edition of Le Defenseur de la Constitution by Gustave Laurent. Gita May also names those three women (using the same source) in her 1964 De Jean-Jacques Rousseau a Manon Roland: Essai sur la Sensibilite Pre-romantique et Revolutionaire. But it's very unclear why Laurent gave these three names in the first place. Certainly Manon Roland must be one of the three, as Robespierre mentioned her salon just a few pages earlier. Sophie de Grouchy (Madame Condorcet) also is a likely candidate as Condorcet is very much a target of Robespierre in that article, and because he mentions secret meetings of the Girondin faction with Lafayette, who was a close personal friend of the Condorcets. I'm not clear why Louise Keralio-Robert should be the third woman. She was not a saloniere, but frequented the salon of her neighbours, the Petions, and she was closer to Robespierre than to the Rolands. Other possible candidates for the third member of the Triumvirate would be Germaine de Stael – Brissot did frequent her salon – or Madame Petion. If any one has information about the identity of this third woman, please contact me or leave a comment!

1 Comment

|

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed