|

Olympe de Gouges was very vocal in her attacks on slavery. What about Manon Roland and Sophie de Grouchy? There is, unfortunately, very little to say.

Manon Roland, when she first began to work out her republican views in writing adopted a similar view:in an essay written in 1777 for the Academy of Besançon, Roland writes that no republic is perfect if it allows slavery, whether Helots in Sparta, or anywhere in the world where women are in (metaphorical) chains, ‘the rust of barbarity covers their proud masters and ruins them together. The poisoned breath of despotism destroys virtue in the bud’ [Roland 1864: 337]. But in her case, she does not even touch on the question of the men and women working as slaves in the French colonies. What makes France despotic, she says, is the existence of a king, and for France to become a republic all that needs happen is for the king to be removed from a position where he dominate the people of France. As a close friend and correspondent of Brissot, it is unlikely that she was unaware of the abolitionist movement, and it seems strange that she chose not to write about it, even in correspondence with Brissot. Perhaps her close involvement with her husband’s political career, and in particular his work at the ministry of the interior meant that her focus had to be elsewhere. In Sophie de Grouchy’s case the absence of any writings of hers on slavery is probably just a function of the very small numbers of her writings we know of and have access to. We have strong reasons to believe, however, that she often worked with her husband, and Condorcet did write on slavery, twice. The first text was written before he knew Grouchy, in 1781, and published in Neufchatel under the pseudonym Joachim Schwartz. However, the text was reprinted in 1822 in an edition by Sophie de Grouchy, preceeded by Condorcet’s last work, the Sketch of Human Progress. It’s very likely that Grouchy had worked on the Sketch with Condorcet, and that she edited it, and made significant changes to the manuscript after his death. Indeed, a later editor, Arago, decided to discard her edition because it was not close enough to the manuscript Condorcet had left. So the fact that Sophie decided to print the work on slavery in the same edition as the work she’d helped write is significant: this is something she could stand by.

0 Comments

Black and White women's characters ( of lack thereof) according to a free man of Saint Domingue11/20/2018 When Julien Raymond explains how racial prejudice grew in Saint Domingue, he says that ‘this prejudice is caused entirely by the jealousy of white women.” But what does he have to say about black women? Before white women arrived, white men, who were sick from their travels, finding it hard to settle in the new climate, and lonely because they had not brought women with them, found comfort in black women. Sometimes they lived with them as if they were married, sometimes they freed them and married them, and sometimes they waited till they bore children to free them, or even simply freed the children, but not their mothers. Black women, Raymond said, made good, attentive companions, because they expected to receive freedom in exchange. When the first wave of white women arrived, they were not the beautiful young women of good family the men had hoped for, and Raymond suggests that women who had travelled alone that far may not be very virtuous. When these women arrived, men continued to prefer black women, who were certainly more compliant, as they still expected to be freed. Throughout the text, blame is piled on white women, but black women are not given a voice. They are described simply as the reward of white men, and the cause of dissensions between families, or a tool for building friendship between them. Their virtue is a function of the law – whether they can be married to white men or not – and they have no self-determination. Raymond does not consider whether a freed black woman could choose to live a life one way or another. And of course – chances are that she could not. Being married to one’s master is still being a relationship of domination, and it is not a marriage that a slave can choose to go into freely. But there is an interesting contrast in Raymond’s text between his treatment of white women (who were probably not given a great choice about abandoning their homes in France to marry a colonist) and of the black women, naturally caring, but unable to choose virtue unless the law makes it their only option. Nonetheless, nowhere does Raymond consider the role white men play, as dominators of black and white women, in the ensuing behaviour and attitudes of these women.

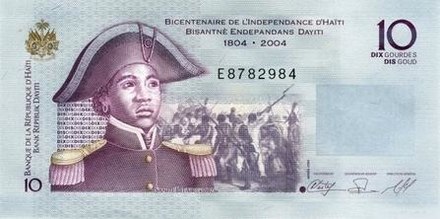

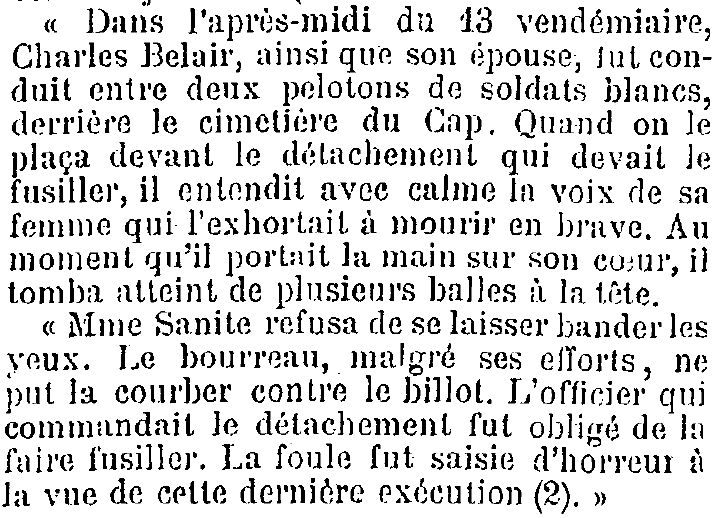

Suzanne Sanité Belair was a young free woman of colour (or possibly an emancipated slave) from Verrette in Haiti. In 1796, at the age of 15 she married Charles Belair, nephew and lieutenant, then general under the leader of the Haitian revolution Toussaint Louverture. The Belair couple worked together and Sanité became a lieutenant in Louverture’s army. The couple was captured together in 1802. The commandant Faustin Répussard of the French army wrote the following account to his General : Following the orders of General Jablonowski I went to the bourg of the small river to report to Dessalines. The next day my national guards were formed into two columns and we walked to [...] Simmonette not far from the Grande fond and I was put in charge of the right column. I then went towards the corai maugerwhere I surprised Diaqoi, Belair’s brother in law, hidden in a ravine. After questioning him to no avail I went in to the woods with my national guard and after a short search I found Madame Charles Belair hidden behind a patch of high grass and I made her come out from behind it and carried on with her to find Belair who I had been told was entranched with some brigands but seeing his wife prisoner he gave himself away. Sanité and Charles were executed on 5 October 1802. He was condemned to the firing squad, but she, as a woman, was to be decapitated. She was 21. The following account was published in an issue of La Fraternité, a Haitian weekly journal, some ninety years later : On the afternoon of the 13 vendemiaire, Charles Belair, with his wife, was taken between two squads of white soldiers behind the Cap cemetery. When he was placed in front of the firing squad he heard the voice of his wife exhorting him to die bravely. At the moment he placed his hand on his heart, he fell, shot to the head with several bullets. This week marked the 215th anniversary of Olympe de Gouge's execution. The French Ministry of Culture thought this was noteworthy enough to make it onto their Twitter feed. The writer notes that Gouges was more than simply a pioneer of feminism. Not that being a pioneer of feminism isn't a good thing in itself, but we know that women philosophers who do only that will get dismissed as lacking in 'universality. But in Gouges' case, it is important to note, as the writer of the Tweet does, the was a prolific writer of political philosophy, openly criticizing first, the King, and then the Jacobins. And she was one of the earliest French philosophers to argue against slavery.

|

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed