|

The French translation of Wollstonecraft's Vindication of the Rights of Woman was published before she arrived in Paris in the winter 1792, and reviewed favourably in at least four reviews, including one, La Chronique de Paris, edited by Condorcet. The name of the translator is not noted anywhere in the translation. Isabelle Bour, in an article on the reception of Wollstonecraft in revolutionary France, suggests that it was a Girondin. The translation is a good one: it contains spelling mistakes rather than mistakes in translation, suggesting that it was done in a hurry by someone who knew English well. It is also annotated in a way that suggests familiarity with English culture and literature, and a desire to defend 'Papist' France against the allegations of a protestant writer, while at the same time poking fun at Wollstonecraft's old fashion religiosity. The translator seems thoroughly on board with Wollstonecraft's defence of women, until, that is, we reach a footnote to Chapter 11 (which mostly concerns education of women) where we get a peak at the translators's common-revolutionary-garden variety and insidious sexism: Here the author is talking about France. It is true that the Revolution is allowing us to pay attention to women who for too long were treated with superficial respect and deep contempt. We owe them a better education; because mothers are the first teachers that nature and society offers children. We owe them divorce, which only the tyranny of priests was able to take from them. A large number among them have proven that they were worthy of liberty; they only need to be enlightened. More enlightened, they will become more virtuous and happier. We owe them reparation for all the gothic crimes of feudality against them, for inheritance, etc.; for if nature seems to refuse them political rights, they have as many claims to civil rights as men. In a word, it is up to them to give the new regime the firmness it needs. Since the French nation has shaken off it yoke, we have heard much about a counter-revolution. Legislators! Don't deceive yourselves: if there is to be a counter-revolution, it will come from the influence of women. So let the constitution concern itself with them, what you do for them will not be lost. What you have deposited in the hands of the paterfamilias really belongs to them, as they will transmit it to the future generations. The translator is quite clear that women are not and should not be political rights holders, and that the main reason why we should grant them rights is that they are mothers to future citizens.

Although Wollstonecraft does emphasise the importance of the role of women as mothers in a republic, she by no means reduces their citizenship to that, indeed, takes pain to say that women need not marry nor have children, but that they still deserve to be treated as full citizens. The translator clearly accepts what Sieyes proposed in the draft of the Constitution, namely that women should be only passive citizen, i.e. enjoy civil, but not political rights.

0 Comments

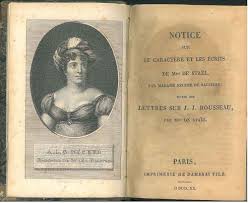

I was alerted by Eveline Groot, who gave a great talk this week at the Braga Colloquium on Women and the Canon, to yet another slight in the history of philosophy against a woman. This time, it's against Germaine de Stael, a writer who saw her share of slights in her life time, including some from Manon Roland and Sophie de Grouchy. But what Eveline Groot found is a 20th century historian of philosophy (or philology), who chooses to minimize the impact and import of Stael's philosophical commentary on Rousseau. Writing in 1915 in Modern Philology (13:7), G.A. Underwood claims that in her reading of Rousseau, Madame de Stael saw only the sentimentalist of the New Heloise, and not the rationalist of the On Social Contract, and that her Notice sur le Caractere et les Ecrits de J.J. Rousseau demonstrate 'little beyond an enthusiasm for Rousseau's ideas' (adding that the enthusiasm itself was significant'. Underwood concludes the introduction to his paper on Stael's interpretation of Rousseau by announcing that: 'The thesis will be that Rousseau leads Madame de Stael to become absorbed in her feelings'. The conclusion of the paper reads as follows: Such is the somewhat undeveloped Rousseauism of Madame de Stael when she began writing. It is an emphasis on temperamental inclination rather than a ripened criticism. A continuation of this study would show how in her mature and original work Madame de Stael gradually thought out to definite literary and philosophical tenets those ideas of Rousseau to which she was so strongly attracted. So one may well wonder why Underwood decided to write the article showing that in her early work, Stael was not a proper philosopher, but yet another female with inflamed emotions, rather than study the philosophical tenets he agrees she later came up with.

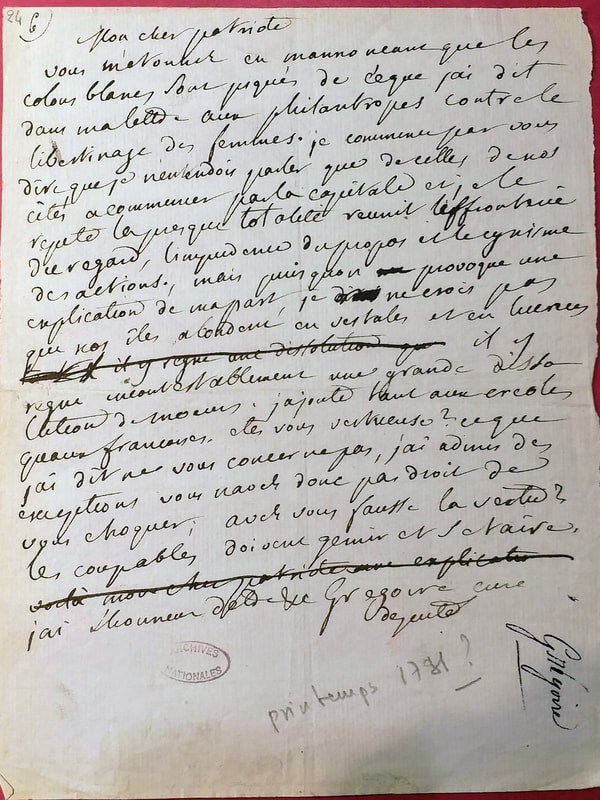

We can add G.A. Underwood to the list of scholars for whom, when it comes to the study of women philosophers, the important work to be done is to show how uninteresting and un-philosophical their work was. Henri Grégoire, known as the Abbé Grégoire, a catholic priest with jansenist sympathies, leading member of the Third Estate, Constitutional Bishop of Blois, was an important figure in the French Revolution, especially for his work against slavery in the French colonies. Grégoire, a close friend of Brissot, one of the few Girondins to survive the Terror, kept on fighting for abolitionism until his death in 1820. Given their shared enthusiasm for abolition, and the fact that they moved in the same circles it may seem surprising that his name and Olympe de Gouges' are not found together more often, or that there is no correspondence between them. When I was in the Archives Nationales, I found out why: Grégoire may have a great abolitionist, but his treatment of women did not measure up. The first clue as to Grégoire's attitude is a footnote from his 'Lettre aux philanthropes', (p. 19, note 1) written in 1790, to shame the French into action in the colonies: Readers, I confess to you, in great secrecy, a story about myself that the white colonists are murmuring to each other: 'it is not surprising that he defends the mixed bloods because his brother has married a woman of colour'. Honestly, if I did have a virtuous mixed-raced sister in law, I would prize her more than I do the near totality of your women, whose amiability receives such praise, but who cannot even, underneath their apocryphal modesty, conceal the ugliness of their vice; and who are all at once brazen in their gaze, impudent in their talk, and cynical in their acts. One might be prepared to forgive and forget – this is after all only a footnote, if it were not for a letter written to Brissot a few months later, in which he more than reiterated his views on women:

In other words, some women may be virtuous, most are not. Either way – women should shut up.

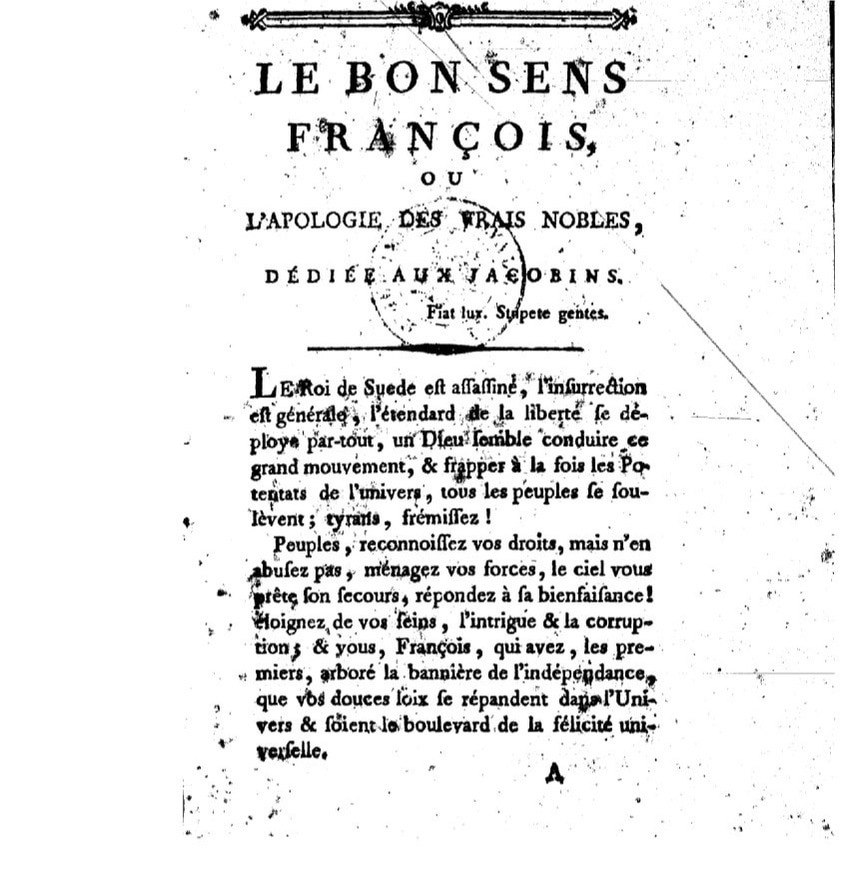

Olympe de Gouges was in the habit of relating personal anecdotes at then end of her published texts. So for instance, the story of how she travelled from Auteuil to Paris, and the evidence that she corrected her own proofs is printed at the end of the Declaration des Droits de la Femme. In a 1791 text entitled "Le Bon Sens François" she tells an amusing story about what happened when she overheard two men in a coach talking about the famous author Olympe de Gouges. She interrupted the conversation: -"So you know her quite well?" - "Certainly. Her husband was a cook: she refuses to bear his name! No one knows who her father is. As to her works, not one word comes from her. She cannot read, they were written for her, affecting carelessness and ignorance in the style to make it seem that they are hers." - "But I have seen her draft a piece in front of several witnesses, and she even won a bet by doing so." Replied Olympe. - "Ah! Madam! The play was written for her in advance and she was made to learn by heart." - "Are you quite sure?" - "So sure that I am prepared to bet she could not do the same again in front of me. Besides I know what I am talking about - I am one of her fortunate admirers." Olympe gave her final reply as she was leaving the car: - "Sir, I have listened to your idiotic claims with the calm of a philosopher, the courage of a man and the eye of an observer. I am this same Olympe de Gouges that you never did know and never could. Take advantage of the lesson I am giving you: men like you are common enough, but women like me are the work of several centuries." [Dialogue adapted and translated from Olivier Blanc, Olympe de Gouges, p. 76.] In 1788, when Olympe de Gouges printed the first volume of her Works, she included a play titled Le Mariage Inattendu de Cherubin. This play had been written in homage to Beaumarchais's Marriage of Figaro, and Olympe was hoping to attract the great author's interest or patronage. Unfortunately all she attracted was his ire. Beaumarchais decided, without having read it, that her play plagiarized his and he instructed the actors of the French theatre, with whom he has a great influence, not to take it. Undeterred, Olympe decided that she would make the best of things and seek actual feedback from Beaumarchais on her work. She wrote him a note, and like Manon Roland with Rousseau, she went to knock at his door, hoping for an interview. The note she handed at the door said:

I come to you as the oppressed come to Voltaire's. I am at your door, and I flatter myself that you will do me the honor to see me.' Beaumarchais' servant took the note to his master and came back with the response that Beaumarchais was busy and could not see her right now. Olympe asked for his at home day, so that she could come back when he was not busy, but was told that Beaumarchais could not be certain of when he would be free. Olympe left in a huff. Four months later, she published her account of the incident in the preface of the play. Unlike Manon Roland, she lacked the delicacy to make light of the incident. Le Mariage Inattendu de Cherubin remained unperformed, until she decided, later on, to take it and others (her reputation with the Theatre Français never quite recovered from Beaumarchais' assault) to the provincial theatres. When Manon Roland was 21 she heard that Rousseau was in Paris and decided to try and meet him. A friend of hers, a fellow Genevese provided the introduction and the reason for the visit: he's commissioned some music from Rousseau and she was to pick it up. So she wrote him a letter and went to his house, accompanied by her nanny. She relates the visit in a letter to her friend Sophie, on 29 February 1776. Thérèse Levasseur with Jean-Jacques Rousseau. When Manon knocked, the door was open by Therese Levasseur who asked her rudely what she wanted.

- "To speak to Monsieur Rousseau - is this his home?" - "What do you want with him?" - "An answer to a letter I wrote a few days ago." - "Well, Miss, you can't speak to him. But you can go and tell the people who made you write - for surely you did not write this letter..." - "Pardon me?" - "The hand itself is clearly a man's." - "Would you like to watch me write?" Laughed Manon. She did not see Rousseau, who was old and sick and saw no visitors anyway, but Manon went back home with, she says, the slight satisfaction that he found her letter well enough written that he thought it could not be by a woman. Manon Roland, we saw, did not like to write in her own name. Her reasons were as follows:

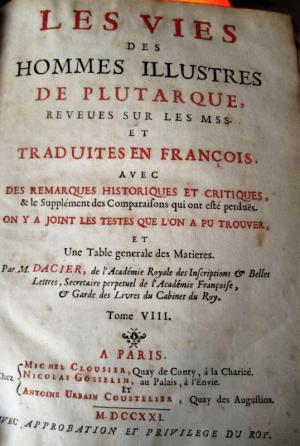

"Never have I had the slightest temptation of becoming an author; very early, I saw that any woman who would earn this title lost much more than she gained. Men do not like her, and her own sex criticize her: if her works are bad, she is mocked, and quite rightly. If they are good, they are taken from her. If one is forced to recognize that she did produce the best part of it, her character, her morals, her behavior and her talents are dissected to the extent that her wit’s repute can be balanced against the weight given to her weaknesses." And she made it clear to others that she knew just how inappropriate it would be for her to become a published author in her own name: “I know full well, Sir, that silence is woman’s ornament; the Greeks thought so and Mrs. Dacier wrote it, and despite our century’s general opposition to this sort of morality, three quarters of sensible men, husbands especially, still live by it.” (Manon Roland, 21 March 1789, letter to Varenne de Fenille), The anecdote Roland alludes to is reported as follows: Mrs Dacier, when asked to autograph the album of a learned German traveller, seeing the names of some very famous writers and scientists above hers, chose to copy this verse from Sophocles out of modesty. (Encyclopediana, Paris: Panckoucke, 1741.) Anne Dacier was in fact a classical scholar of some note, who worked first with her father, and then with her husband on a number of translation of Greek and Roman texts. She became famous for her translation of Homer, and for her preface to it, which was translated into English. She also wrote on aesthetics. Madame Roland was well aware of Dacier's success as an author. When, as a child, she'd read Plutarch's Parallel Lives she used the nine-volume integral translation produced by Anne and Andre Dacier in 1721. (Note, however, that only Andre Dacier is acknowledged as author on the title page). |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed