|

On 19 June 1792, the Jacobin club of Marseilles wrote to Jerome Petion, the mayor of Paris warning him that the King, with his corrupt civil list, was a threat to French Liberty, and that they were ready to come and lend a hand. A few days later, a deputation of 500 Marseillais set off for Paris on foot – over 700 km. Their leader, a captain from Montpellier, sang for them a war song celebrating the Revolution, written by Rouget de Lisle. On 30 July, the Marseillais entered Paris singing that same song. One can only imagine what 500 hungry, thirsty, and possibly ill soldiers suddenly entering the Capital must have been like. And of course, they had come for a reason, to confront the King and defend Liberty. So it’s no surprise perhaps that on 10 August, they took part in the massacre of the Swiss guards in the Tuileries. But before they did, 400 of them made a stop at the Hotel des Monnaies, the home of the Condorcets. The building is not small, nonetheless, making space for, and serving 400 scruffy soldiers must have been a challenge. But if it was, Sophie met it well. According to her biographer, Guillois, she was the ‘Queen of the party’, and that: she charmed them so well that she could have, had the Gironde listened to her, saved, with the help of the Marseillais, Coutnry and Liberty.

0 Comments

One problem with republicanism as it was understood in the late 18thcentury, from a feminist perspective, is that like its ancestor, Roman republicanism, it is a very performative sort of political theory. To be a republican citizen means running around the clubs and the Assembly, getting oneself elected, or electing others, giving speeches, or going to listen to them, writing, printing, distributing, reading pamphlets. And aside from a few pictures of fishwives on their way to Versailles, or the infamous tricoteuses during the Terror’s trials, the imagery of the revolution is very male. Political participation is not the sort of think that you can easily do if you are responsible for the upkeep of a house and the upbringing of children. And Roland, we know, took her domestic role very seriously indeed. So how did she reconcile her perception of herself as a wife and mother on the one hand and as a republican on the other? Part of the answer was that she thought that taking care of home and children was best done as a couple – with her husband fully engaged in the upbringing of their daughter Eudora, and once left in charge of her for several weeks while Manon was in Paris and Versailles. Another answer is that Manon changed her mind when it became apparent to her that the Republic needed her to be active. And she changed her mind again after the September massacres when she decided that the French did not deserve a Republic. But none of this is enough to give a full account of how she did reconcile her belief in the important of domesticity with her republicanism. One more promising clue lies in the essay she wrote for the Academy of Besancon, in which she described the role played by Spartan women in promoting the republic: More sedentary, more enclosed ordinarily in republican governments, left to domestic tasks, nourished by this patriotism which elevates the soul and sentiments, they laboured towards the citizen’s happiness and that of the state, through the peace and order reigning inside their homes, and the care they take to cultivate in their children the germs of courage and virtues that must be perpetuated as well as liberty. Focused on their families, they could not set any other ends for themselves than that of being cherished for the qualities that are needed in the home and that they would be recommended for. The love of little things, seeking vain distinctions is a feature only of superficial societies, where each brings pretensions devoid of real merit to sustain them. What the Spartan women did on this account was to nurture virtues in the family, and that would have carried some weight with an 18th century republican. Whereas we now understand philosophical republicanism mostly in terms of its concept of liberty as non-domination, in the 18th century, it was also veyr much a theory of participation (hence the performative aspect that is so problematic) and of virtue. And what Roland could assert without contradicting herself, is that women who took their domestic duties seriously did in fact participate in the republic, by modeling and nurturing civic virtues.

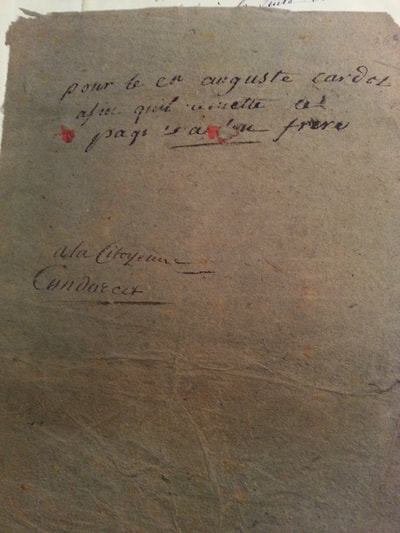

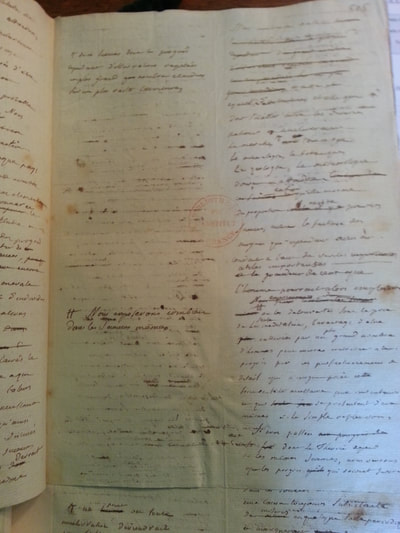

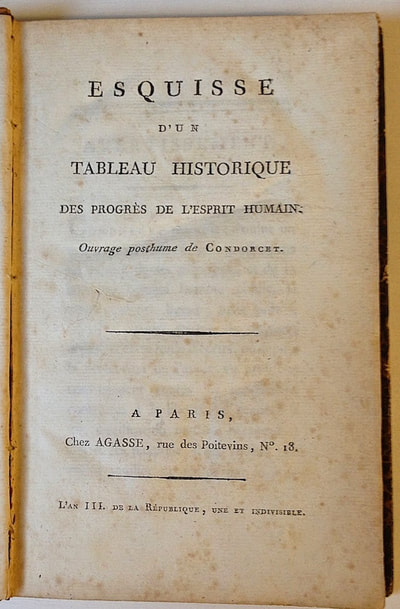

While in hiding, Condorcet started to write an apology (Justification) which was meant to explain and justify his role in the revolution, and show that he had been wronged by his persecutors, the Jacobins. Sophie, sensing that this work would be of little value philosophically or personally, urged him to give it up, and instead to turn back to a work he had begun several decades before: a history of the progress of human nature. Although we do not have any hard evidence that they wrote together, it seems likely that some of the passages in particular are hers, and that others are the product of a collaboration between husband and wife. We do not have a final manuscript that corresponds to the first edition by Grouchy, which suggests that she added some paragraphs herself. The only existing manuscript, dedicated to Sophie, is very messy, and would have required much editing to make sense of the marginal annotations and in text corrections. Several of the differences concern women and the place of the family in human progress. Perhaps these were ideas she and Condorcet had discussed and that she knew he wanted included. Perhaps these were points she had suggested to him in their discussions. In March 1794, Condorcet run away from his hiding place in order to avoid getting his hostess arrested. He died a few days later in a village prison, but was not identified until several months after his death, so that his wife remained ignorant of his whereabouts. When several months later his remains were identified, the Convention commissioned three thousand copies of his new book, Esquisse d’un Tableau des Progrès de l’Esprit Humain from Pierre Daunou. Sophie de Grouchy prepared the edition and it was published in 1795. This edition was reprinted and revised at least twice by Grouchy (alone and with collaborators in 1802 and 1822), and it was translated into English the year it was first published, and John Adams owned a copy In 1847, the Académicien François Arago, noted that the 1795 edition contained passages which were absent from Condorcet’s final manuscript, produced a new edition with extensive revisions, which, he said, was closer to the original manuscript which he’d obtained from Grouchy and Condorcet’s daughter, Eliza O’Connor, and which he thought more accurate because in Condorcet’s hand. Arago’s edition is now regarded as authoritative. Not only was Grouchy’s name deleted from the work – where it did belong, perhaps as co-author and at the very least editor – but with it the emphasis she had brought on the role of women and the family in human development.

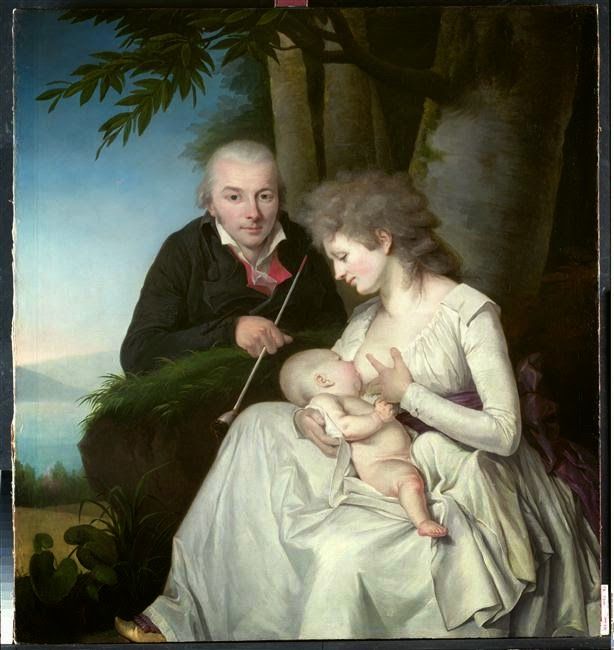

One specific way in which Rousseau’s views on the family were influential during the revolutionary period was his argument that mothers should nurse their own children, rather than sending them out to wet-nurses. This view was very popular among women especially as it was seen by many as reinstating women in society, granting them a form of authority, which stemmed from their ability to nurture future citizens. Despite Rousseau's lack of arguments and his reliance on romantic notions of the mother-infant relationship, many French women writers, including Manon Roland, agreed with him that breastfeeding one’s own child was a moral duty. But these women were not immune to the sort of difficulties that mothers often experience when they breastfeed. That included Manon. Her difficulties were only minor – an illness early on which meant she was too weak to produce milk – and seems to have been able to avoid depression.. But she had to employ the services of her nurse while she was ill and her husband was in Paris on business, and this bothered her: We mustn’t pretend otherwise: she will have the child more often than I at first, especially during this unfortunate convalescence when I am deprived of my strength. She will have her smiles, also. And I, although I will no longer be in pain, will not be repaid by her first caresses for which I would forget anything. This is still making me cry – I cannot forgive my own weakness. My child will not know my breast, she will not throw herself upon it with this urgency, so touching for mothers: why has my milk gone?!” A few weeks later, Manon found a way of getting her milk back. She hired the services of a ‘femme à tirer’ a sort of lactation consultant, who came twice a day to massage her breasts and draw milk. Manon noted an improvement - a permanent drop of milk on the tip of her breasts – and hoped that the milk would soon thicken. In the end she succeeded in breastfeeding her daughter, keeping careful records of her growth, lest her milk was not rich enough.

|

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed