|

Having just returned from the fantastic "Bridging the Gender Gap Through Time" conference in London, I want to share a quote and an image highlighted by my friend and collaborator Alan Coffee during our joint presentation. You may think it too soon to form an opinion of the future government, yet it is impossible to avoid hazarding some conjectures, when every thing whispers me, that names, not principles, are changed, and when I see that the turn of the tide has left the dregs of the old system to corrupt the new. The phenomenon of the common man turned petty tyrant by the Revolution was entirely familiar to Olympe de Gouges, who relates that after a journey from Auteuil to her Paris printer, she was dragged to the police by a disgruntled cab driver who insisted on charging her an exorbitant price for the journey. [...] I owed the coachman for an hour and a half but in order not to get into a fight with him I offered him 48 sous; as usual he loudly demanded more I stubbornly refused to give him more than his due for an equitable soul would rather be generous than duped. I threatened him with the law; he said he cared nothing for it and insisted that I pay him for two hours. We arrived at a justice of the peace, whom I shall generously not name, although the authoritarian way he dealt with me merits a formal denunciation. No doubt he was unaware that the woman asking for justice was the authoress of so many charitable and equitable works. Paying no attention to my reasons he pitilessly condemned me to pay the coachman what he demanded. Knowing the law better than he did I said to him, ‘Sir, I refuse and I would beg you to be aware that you are exceeding the prerogative of your position.’ So this man, or to put it better this lunatic, got carried away and threatened me with La Force [prison] if I did not pay straightaway, or he would keep me in his office all day. I asked him to take me to the district tribunal, or the town hall, as I needed to lodge a complaint against his abuse of power. The grave magistrate, in a riding coat as dusty and disgusting as his conversation, tells me pleasantly: ‘No doubt this affair must reach the National Assembly?’ ‘That may well be.’ I said, half furious and half laughing at this modern-day Bride-Oison, ‘So this is the type of man who is to judge an enlightened People!’ This sort of thing abounds. Good patriots, as well as bad ones, indiscriminately suffer similar misadventures. There is but one cry concerning the disorder of the sections and tribunals. Justice has no voice; the law is disregarded and, God knows how, the police are inured.

0 Comments

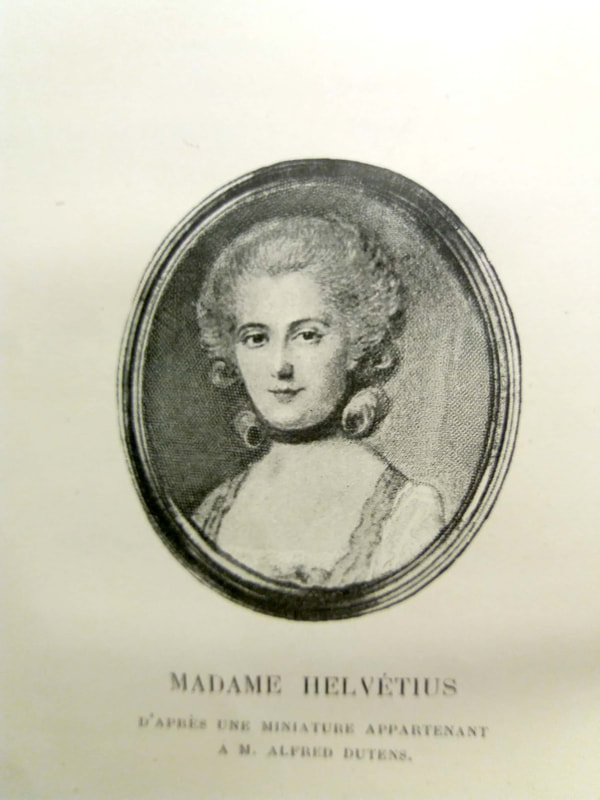

Before she became Madame Helvetius, the famous hostess of the Auteuil salon in which our heroines and their friends met to discuss politics and philosophy, Anne-Catherine de Ligneville was destined for convent life.

One of twenty children in an impoverished aristocratic family, there was no money to marry her. But before she could be sent off to a convent, Anne-Catherine was adopted by an aunt, Madame de Graffigny. Madame de Graffigny had no children of her own, and an abusive, violent husband, whom she kept at bay as much as possible. She certainly did not want a child from him. Madame de Graffigny was a friend of Voltaire and he invited her to join him and Madame du Chatelet at Cirey while she arranged to leave her husband. Unfortunately, she wrote some rather indiscreet letters while she was there, including one describing in details a very contentious play by Voltaire, La Pucelle. Chatelet, who read all incoming and outgoing mail, took exception. She had dedicated her life to preventing Voltaire from being sent to the Bastille for his writings, and would not have a guest endangering him for the sake of gossip. Soon afterwards, Madame to Graffigny moved to Paris with Anne-Catherine, whom she called affectionately Minette. She had adopted her niece with the intention of educating her and introducing her to Paris Society. As she was not rich, in order to succeed in the latter, she had to become famous. That she did with the publication of her novel, Lettres d'une Peruvienne, a satirical account of French life viewed by a kidnapped Inca princess who is introduced to the Paris society. Madame de Graffigny's salon became famous, and so did her niece. Before the philosopher and dandy Helvetius cast his eyes and intentions on Minette, she became a close friend of Turgot, then a priest, and together, they played badminton. When Olympe first came to Paris, she was able to mix with the aristocracy through her half brother, Pompignan's heir. But her big break as an author was an introduction, through her friends Louis Sebastien Mercier and Michel de Cubière, to the salons of Fanny Beauharnais and Madame de Montesson. Cubiere was a poet, a socialite and a flirt, whose official mistress was Fanny de Beauharnais. During the revolution he used his charms to make a place for himself in the ever changing government, and it is to him that Olympe attempted to write when she was first taken. Cubière survived the revolution. Mercier, poet, novelist, playwright and philosopher, also survived, despite being put under arrest in 1794 for having protested the sentencing of the Girondins. Madame de Montesson was a talented widow, who became a patron of playwrights welcoming in particular those, like Olympe, who had experienced difficulties with the Comédie Francaise. She set up a private theatre in her Paris home in the Chaussée d’Antin, close to Mirabeau’s home, as well as a number of other famous literary salons of the 18th century such as that of Juliette Recamier or Louise d’Epinay. Her theatrical manager was Joseph Boulogne, the Chevalier de Saint George, a composer and soldier born of a rich planter and his Guadeloupean slave, Nanon. Saint-George became one of Madame de Montesson’s protegés after his first Opera, Ernestine with a libretto by Choderlos de Laclos, failed miserably at the Comédie Italienne. In 1792 Saint-George was put in charge of a legion of soldiers who were also men of colour and fought under the celebrated General Dumouriez.

On 7 November 2017, 314 Francophone teachers signed and published a document promising not to teach or enforce a particular rule of French grammar:

"Le masculin l'emporte sur le féminin" - that is, when a noun group is of mixed gender, the corresponding pronouns and adjectives should be written in the masculine form, because that form is 'stronger' or 'wins over' the feminine one. For instance, a group of men reading is refered to as 'lecteurs', a group of women reading as 'lectrices' but a mixed group as 'lecteurs'. Proponents of Inclusive Writing suggest that it should be 'lecteur·rice·s' The guardians of the French language, the Academicians, who are in charge of vetting new dictionary entries and proposals for grammatical reform, immediately rose against the proposal, declaring it to constitute a 'mortal danger' for the French language'. The minister of education, Jean-Michel Blanquer, agreed, adding that it was 'very ugly' and that real feminists should concern themselves with other, more important problems. The Prime Minister Edouard Philippe followed suite, declaring that the new 'écriture inclusive' would not be legal in official documents. Two years before the petition for inclusive writing was signed, historian Eliane Viennot addressed the National Assembly on the need to reform language. She has since been an active member of the movement and noted that far from being new, the idea that language should be reformed to include women as equals dates back, in France, to the Revolution, and in particular to Olympe de Gouges. According to Viennot, Gouges's Declaration of the Rights of Woman was a direct challenge to the failure to include women in the new Constitution. Viennot points out that 'l'homme' in French does not, and never did correspond to 'humanity', but really only to male humanity. Counting the number of uses of the word in several authors of the Enlightenment, she says it is clear that the word is not meant to include women, except on a few occasions. Pretending that the use of the masculine is neutral or universal is pure hypocrisy - except if we understand 'universal to mean 'applying to men only' which in the French 'universal suffrage' of 1848 , it did. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed