|

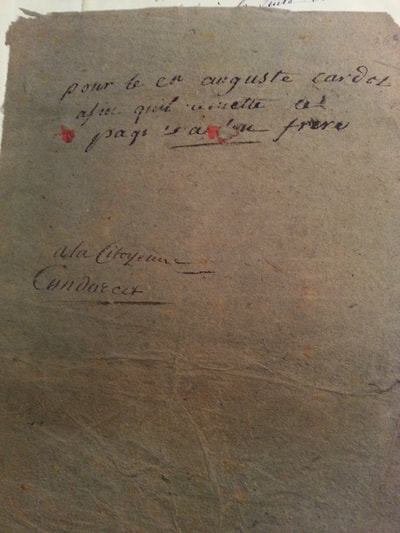

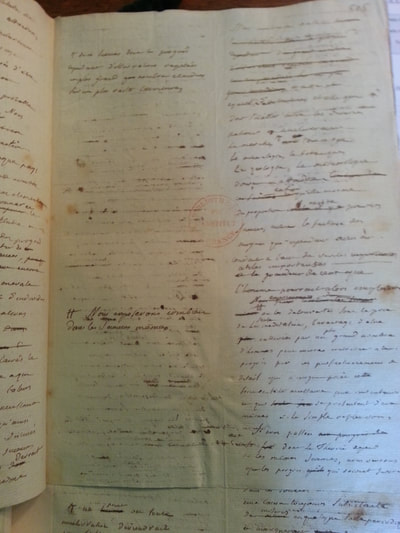

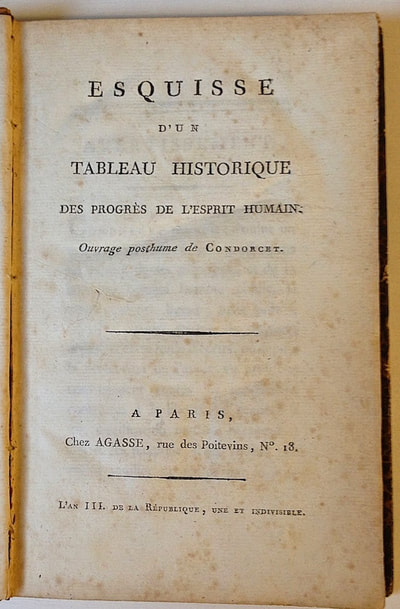

While in hiding, Condorcet started to write an apology (Justification) which was meant to explain and justify his role in the revolution, and show that he had been wronged by his persecutors, the Jacobins. Sophie, sensing that this work would be of little value philosophically or personally, urged him to give it up, and instead to turn back to a work he had begun several decades before: a history of the progress of human nature. Although we do not have any hard evidence that they wrote together, it seems likely that some of the passages in particular are hers, and that others are the product of a collaboration between husband and wife. We do not have a final manuscript that corresponds to the first edition by Grouchy, which suggests that she added some paragraphs herself. The only existing manuscript, dedicated to Sophie, is very messy, and would have required much editing to make sense of the marginal annotations and in text corrections. Several of the differences concern women and the place of the family in human progress. Perhaps these were ideas she and Condorcet had discussed and that she knew he wanted included. Perhaps these were points she had suggested to him in their discussions. In March 1794, Condorcet run away from his hiding place in order to avoid getting his hostess arrested. He died a few days later in a village prison, but was not identified until several months after his death, so that his wife remained ignorant of his whereabouts. When several months later his remains were identified, the Convention commissioned three thousand copies of his new book, Esquisse d’un Tableau des Progrès de l’Esprit Humain from Pierre Daunou. Sophie de Grouchy prepared the edition and it was published in 1795. This edition was reprinted and revised at least twice by Grouchy (alone and with collaborators in 1802 and 1822), and it was translated into English the year it was first published, and John Adams owned a copy In 1847, the Académicien François Arago, noted that the 1795 edition contained passages which were absent from Condorcet’s final manuscript, produced a new edition with extensive revisions, which, he said, was closer to the original manuscript which he’d obtained from Grouchy and Condorcet’s daughter, Eliza O’Connor, and which he thought more accurate because in Condorcet’s hand. Arago’s edition is now regarded as authoritative. Not only was Grouchy’s name deleted from the work – where it did belong, perhaps as co-author and at the very least editor – but with it the emphasis she had brought on the role of women and the family in human development.

0 Comments

Just as Olympe de Gouges did, Sophie de Grouchy had to relocate to the suburbs during the Terror. In 1793, the Jacobin Chabot had issued an order to arrest her husband, Condorcet. Condorcet had gone into hiding in the house of Madame Vernet, on the Rue des Fossoyeurs (now the Rue Servandoni). Their property was confiscated by the government, and Sophie, together with her young daughter, her nanny and her sister Charlotte, moved to a house on the Grande Rue D'Auteuil, not far from where Madame Helvetius lived. Several times a week, Sophie walked into Paris to visit her husband. As she did not want to be recognised, or to attract anybody's attention to Condorcet's hiding place, she came dressed as a peasant woman, pretending to be with the crowds of farmers come to sell their goods to the starving capital. Once through the gates, she would lose herself in the crowds come to see that day's executions at the Place de la Revolution (now Place de la Concorde), then cross the river to reach the left bank, and walked towards the church of St Sulpice, and beyond that to the street where her husband was hiding. Often she would bring him books, or notes that he needed for his work - as he'd had to leave home in a hurry. She would also stay and encourage him, and work with him. His last work, the Sketch of human progress, was almost certainly something they worked on together. After seeing her husband, Sophie would walk back across the Seine towards the Rue St Honoré, where she rented an underwear shop and the half-floor above it. Putting Auguste Cardot, younger brother of her husband's secretary, in charge of the shop, she set up a studio in the alcove and worked on her miniatures from there. Thus she insured that she had sufficient income to see to the needs of her husband, her family and herself until she could claim back some of what the government had seized.

|

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed