|

When Paine submitted his 'Letter' to his friends Brissot and Condorcet to publish as an advertisement for their new paper Le Républicain, it needed to be translated. Paine spoke and read French, but didn't like to write it. It had been decided, for some reason, that Achille Duchatellet, not Paine, would sign the article before it was pasted all over Paris, and published first, in Brissot's Patriote François, and then as the leading article of Le Républicain. Etienne Dumont, translator of of Jeremy Bentham, was approached first. Dumont refused, on the grounds that he did not want to be involved in what he saw as a foolhardy enterprise by 'an American and a young fool from the French aristocracy who put themselves forward to change the face of France' . The other member of the team who was able to translate was Sophie - hence, she probably got the job. But Sophie's participation in the journal did not end with translation. Two anonymous articles may be attributed to her. The first is very short. Entitled "Letter from a young mechanic" it proposes that the royal family and its entourage be replaced by a set of automaton. Even though such machines are expensive, they will cost a fraction of what the French people are spending on their actual king. And what's more, the mechanical king, far from being a tyrant, will raise its pen and sign everything its government wants it to! The second article is a long and very critical piece on the King and the mechanisms of his government. This article, it seems, was originally supposed to be written by Dumont, but he withdrew, when the king was returned to Paris. Dumont, however, had left a set of notes at the Condorcet. He later complained in his memoires:

There is good stylistic evidence that the person who 'rewrote' Dumont's piece was in fact Sophie. In particular, an image she uses in her Letters on Sympathy can be found in the article, that of the king (and monarchy) as a rattle designed to amuse the immature French people, to distract them from the fact that they are not free.

0 Comments

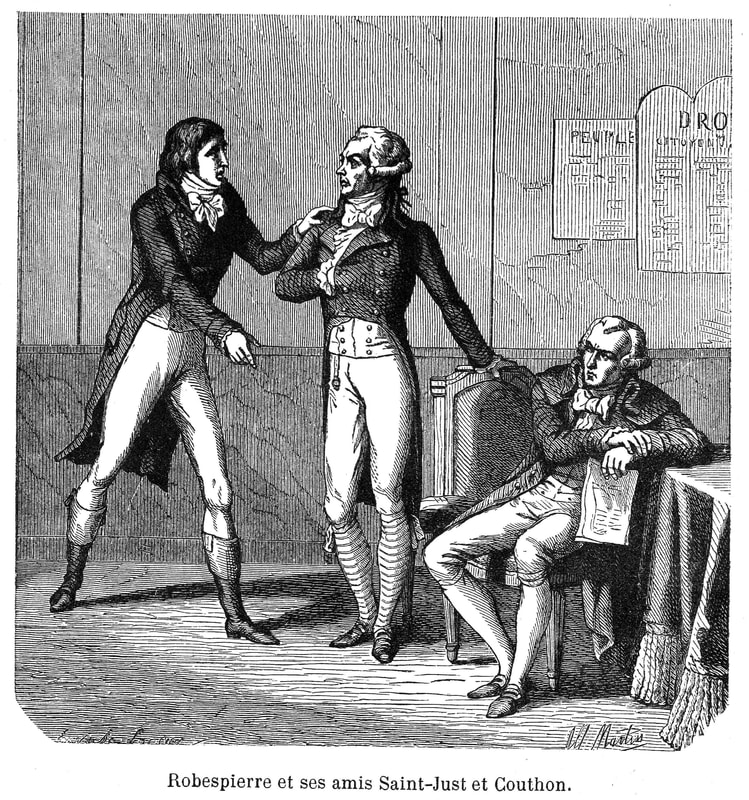

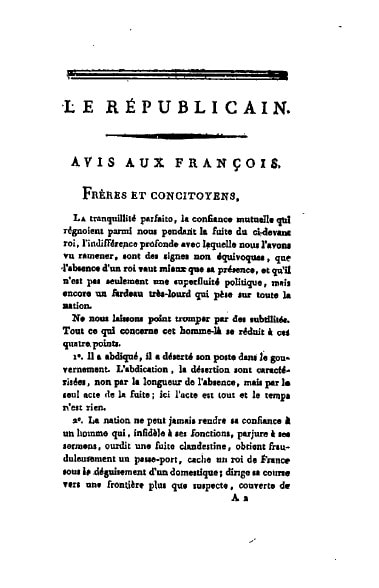

On 21 June 1791, . the King of France had just escaped with his family, dressed as middle class people, and hoping to reach Austria. At lunch at the Petions with Brissot and Robespierre also present, the Rolands were discussing what the Assembly should do next. The idea of a republic was first mentioned. At that point, according to Manon Roland, "Robespierre with his habitual grimace, and biting his nails asked 'What is a Republic?'" This was also, Manon claimed, when the project of a republican society and the journal "Le Republicain" were first imagined. The journal was very short lived, with only four issues printed, It was in fact the work of Condorcet, Brissot, Thomas Paine, Achille Duchatelet, Etienne Dumont and (as we will see in a future post), Sophie de Grouchy. It was first advertised through a pamphlet, written by Paine, translated by Grouchy, and signed by Duchatellet. Manon, writing to Bancal in July 91 reported that the opening of the new society had caused quite a scandal at the Assembly: You know that a new republican society was formed, and they are to bring out a paper, the title of which advertises its goals and principles. Payne is at the head of it. He wrote the content of the pamphlet that is pasted everywhere this morning, as a sort of notice. Malouet denounces this pamphet as deserving the of the harshest punishment. The worst thunder was at the assembly, and it is only by flattering its love for the monarchy, and hatred of republicanism that we succeeded in convincing it that whatever the opinion, it should be let to run free [...] The Jacobins, like the Assembly, go into convulsions whenever the Republic is mentioned” Mme Roland, |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed