|

In 1783 Olympe wrote her first play, Zamore et Mirza, ou l’heureux naufrage, and submitted to the Comédie Française. The actors liked it and accepted it. Unfortunately, her later dispute with Beaumarchais over Le Marriage Innatendu de Chérubin, meant that the Comédie just sat on her play and refused to put it on. The contract she had signed with them meant that it could not be played elsewhere in Paris. So Olympe took the play elsewhere, with her own theatrical troup, which included her son, and performed it in private theatres and in the provinces. In 1786, she had the play printed for the fist time. Two years later, she printed it again, with a postface, her “Réflections sur les hommes nègres” in which she explained what the philosophy behind the play was. Why are black people treated like animals, she asked? [I] clearly observed that it was force and prejudice that had condemned them to this horrible slavery, that Nature had no part in it and that the unjust and powerful interest of the Whites was responsible for it all. In 1788, Olympe was already sensing a change for the better in politics, and felt it her duties to show the world that if they wanted to redress injustice, slavery was the place to start: When will work be undertaken to change it, or at least to temper it? I know nothing of Governments' Politics, but they are fair, and never has Natural Law been more in evidence. They cast a benevolent eye on all the worst abuses. Man everywhere is equal. As she pointed out in January 1790, in an open letter to an (anonymous) American colonist attacking her play, at the time she wrote Zamore and Mirza, there was no organised French abolitionist movement. The Societé des Amis des Noirs did not yet exist. She ponders in that letter, whether it was her play that caused Brissot and the others to create that society, or whether it was just a happy coincidence: I can therefore assure you, Sir, that the Friends of the Blacks did not exist when I conceived of this subject, and you should rather suppose that it is perhaps because of my drama that this society was formed, or that I had the happy honour of coincidence with it. In fact, Brissot did take note of the play, and in the winter 1789, he made use of his growing influence to persuade the actors of the Comédie Française, finally to put it on. Unfortunately, the actors bore a grudge, so they arranged for the play to be put on on the last day of the year, after which Parisians would be returning to their family homes to celebrate the New Year. The contract required that a play make a certain amount of money in the first three days if it was to stay on the program. The first night was a success – but a political rather than an artistic one. People came to support it and to protest against it, and they were so loud about it, that few could hear the actors. Fortunately the text was in print, and reviewers at the time noted that they’d had to refer to the printed version to know how the play ended. Those who protested against the play most vociferously were the colonists, who had strong financial interest in the laws regarding slavery staying as they were. One such colonist wrote to Gouges, imputing that she was but the tool of Brissot’s society, and that her play was a call for the slaves of America to revolt. Gouges responded in an open letter, (1790) arguing, as we saw, that it was she, not Brissot, who’d first given voice to the abolitionist in France, and that her play did not incite revolution, but that it enjoined the French people and the colonists to see that all men were equal and abolish slavery, and the slaves to trust in the new laws and wait for a better future. Two years later, these accusations came back when the slaves and the free people of colour of Saint-Domingue revolted.

0 Comments

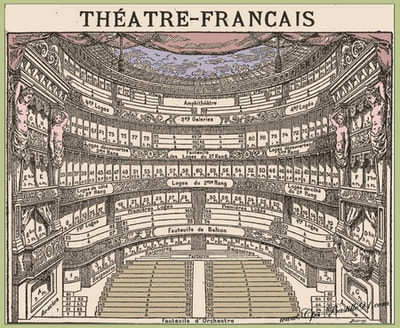

At the end of a treatise in which she takes on Rousseau's analysis of human progress, Olympe de Gouges makes the following proposal: a second French theatre, or The National Theatre. A great number of well-born women are ruined because men, who have seized everything for themselves have prevented women to elevate themselves, and to obtain for themselves useful and lasting resources. Why should my sex not one day be rescued from this thoughtlessness to which their lack of emulation exposes them? Women have always written. They have been allowed to contend with men in the theatrical profession. But they would need proof of greater encouragement. Such is my plan: She goes on to describe an institution that would take in children from respectable but poor families, educate them in the arts and train them as actors, but always with a view to their respectability. After a few years, these children would constitute a troop of actors and would be offered the opportunity to produce plays. Those that chose not to, could pursue any other career in the arts. But as many of the fashionable plays of the times were not, to Olympe's mind, respectable, she would enlist the help of writers who are not given to scurrulous plots, and whose works are not usually performed, i.e. women. She says she herself has 32 plays ready to go, and that many other women have penned good plays.

Thus Olympe aims to kill two birds with one stone: Give women playwrights the chance to work, and reform the arts by providing a national artistic education so that would be artists do not resort to demeaning themselves in order to pursue their arts. Olympe de Gouges, when writing her play about slavery, Zamore and Mirza, or the Fortunate Shipwreck, displayed a certain amount of confusion about the geographical setting and the people she depicted. The play is described as an Indian drama. The Action is said to take in the East Indies. The main characters, Zamore and Mirza are described as Indians and another as governor of a Town and a French Colony in India. There are also 'several local indians'. Gouges describes a ballet that is take place at the end of the performance where Indians and soldiers mix, and which is to represent the discovery of America. In a postcript she added to the play, she recommended that the theatrical company 'adopt both the colour and the dress of the Negro.' thereby contradicting apparent claims that her protagonists are either Asian or native Americans. Although the French did colonize India, it is not clear that this is supposed to be the setting of the play. Rather, the West Indies is where the French had slaves. What about East Indies? The French did again colonise Vietnam, then Indochina, but this was not where the slave trade was conducted. On the other hand, the French East India Company had interest in Mauritius and Reunion (Ile de France and Ile de Bourbon), both, in the West Indies. The proximity of the West Indies to America may have led to the idea of a ballet re-enacting the discovery of America. What can we make of such racial ignorance and inept geography? Of course Olympe was largely uneducated. And the anti-slavery movement in France was yet to grow strong enough that many people were aware of the specifics of the slave trade and of the conditions of living in the West Indies. In fact, Gouges was one of those who helped bring the evil of slavery to the attention of the French public, and Brissot, one of the founders of the Club des Amis des Noirs, claimed to be influenced by her play, and offered her a membership to the abolitionist club as soon as it was founded. Olympe was ignorant, but she did not, as an 18th century woman, have much of an opportunity to educate herself by travelling. She was confused, but had good intentions: she felt that by portraying courageous, intelligent and compassionate runaway slaves, she would spread the word about the abuse that was perpetrated and interest the public in helping stop that abuse. Poor education, lack of opportunity, good intentions all sound like the sort of excuses given for every day racism and cultural appropriation. Does it make sense to see in Zamore and Mirza the beginnings of these phenomena? Ballet - at the end of the last act. In 1788, when Olympe de Gouges printed the first volume of her Works, she included a play titled Le Mariage Inattendu de Cherubin. This play had been written in homage to Beaumarchais's Marriage of Figaro, and Olympe was hoping to attract the great author's interest or patronage. Unfortunately all she attracted was his ire. Beaumarchais decided, without having read it, that her play plagiarized his and he instructed the actors of the French theatre, with whom he has a great influence, not to take it. Undeterred, Olympe decided that she would make the best of things and seek actual feedback from Beaumarchais on her work. She wrote him a note, and like Manon Roland with Rousseau, she went to knock at his door, hoping for an interview. The note she handed at the door said:

I come to you as the oppressed come to Voltaire's. I am at your door, and I flatter myself that you will do me the honor to see me.' Beaumarchais' servant took the note to his master and came back with the response that Beaumarchais was busy and could not see her right now. Olympe asked for his at home day, so that she could come back when he was not busy, but was told that Beaumarchais could not be certain of when he would be free. Olympe left in a huff. Four months later, she published her account of the incident in the preface of the play. Unlike Manon Roland, she lacked the delicacy to make light of the incident. Le Mariage Inattendu de Cherubin remained unperformed, until she decided, later on, to take it and others (her reputation with the Theatre Français never quite recovered from Beaumarchais' assault) to the provincial theatres. |

About

This is where I live blog about my new book project, an intellectual biography of three French Revolutionary women philosophers. Categories

All

Archives

November 2022

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed